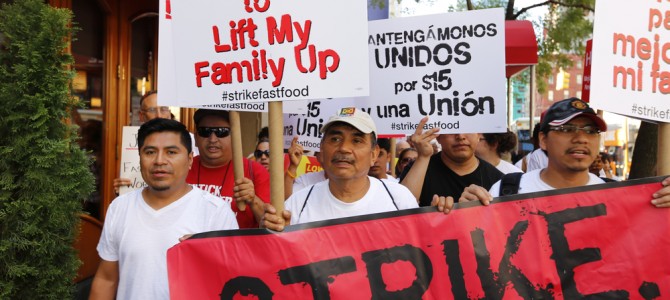

On April 15, the Service Employees International Union is organizing nationwide fast food worker strikes to draw attention to its push for a $15 hourly wage. While such protests may seem to be grassroots efforts led by struggling workers, major unions fund and promote them. Unions desperately need to extend their reach to the high-turnover fast food industry if they are to stem sharply declining membership rolls.

Unions often make contact and generate political activism from low-wage employees through what they call “worker centers,” which conduct activities similar to those of unions but with fewer legal restrictions and oversight. My Manhattan Institute colleague Diana Furchtgott-Roth argues these worker centers are doing unions’ dirty work. As she wrote during similar strikes in November 2013, “Unlike worker centers, unions must hold supervised elections so that members can elect union officials as representatives. Worker centers do not necessarily represent employees. Employees can decertify a union—dismiss it from representing them—but they cannot dismiss a worker center” (emphasis added).

Worker Centers Are Union Branches

Unions are organized as 501(c)(5) entities. They need to hold elections, file detailed financial reports with the Labor Department, and cannot receive tax-deductible contributions. Alternatively, many worker centers are organized as 501(c)(3) charities, which means they can receive tax-deductible donations and they are not accountable to the workers they claim to represent.

Recently-released union financial reports show the strong financial connections between unions and worker centers. Among the prominent worker centers that received funding from the Service Employees International Union’s (SEIU’s) national headquarters in 2014 were Interfaith Worker Justice ($50,000) and New York Communities for Change ($50,000). NYCC is a remnant of the disgraced community organizing group ACORN, which was investigated multiple times for fraudulent voter registration and financial fraud. The rebranding effort was not comprehensive, as NYCC remains at the same Brooklyn address that ACORN occupied. Jobs with Justice, a labor organizing group that does not consider itself a worker center, received $226,600 from SEIU.

Union financial support of worker centers does not end with the SEIU. Last year, the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union gave Jobs with Justice $223,000, Interfaith Worker Justice $117,000, and NYCC $5,000. These two unions stand to benefit the most from unionizing fast food workers.

Unions Twist Fast-Food Data

Perhaps the most effective worker center in terms of gaining press attention has been the SEIU-sponsored Fight for $15, previously known as Fast Food Forward. The latest push by Fight for $15 concerns on-the-job safety conditions for fast-food workers. Fight for $15 cites a survey by Hart Research Associates that claims to show four in five fast-food workers were burned on the job last year. If this statistic were true, it would be damning—but it is not.

In 2014, about 3.7 million Americans worked in the fast-food industry. The American Burn Association estimates that 450,000 burns each year require medical treatment, including 40,000 hospitalizations (although admittedly many burns do not require professional medical treatment). If Hart Research’s claim (based off undisclosed survey questions given to 1,426 fast-food workers) were true, nearly 3 million fast-food workers would have been burned last year.

Considering that fast-food workers make up 2 percent of the labor force and just over 1 percent of the population, it is extremely unlikely that this portion of the population experiences more than six times the amount of total U.S. burns that require medical treatment. This false information does not stand up to the slightest scrutiny and shows that union efforts to bring fast-food workers into their ranks have sunk to new lows.

Let’s Talk about Price Increases

Last year, worker centers also twisted the data. In April 2014, they designated “High Road Restaurant Week.” Restaurant Opportunities Centers United, a worker center that also advocates for a $15-an-hour minimum wage, organized the event and rated restaurants in Manhattan and Brooklyn on their employment practices. Its rating was comprised of metrics including compliance with regulations, a worker-friendly environment, and generous employment benefits. Although proponents of raising the minimum wage argue doing so would not lead to noticeable price increases, If ROC’s list of approved high-road restaurants is any indication, this argument is blatantly false.

The consumer watchdog ROC Exposed examined the prices and menus at the 27 Manhattan restaurants designated as “high road” by the Restaurant Opportunities Center and found that the average price for a burger and fries at these restaurants was $20.50. For the sake of comparison, $20.50 spent at McDonald’s could buy a Big Mac, Double Quarter Pounder with cheese, McDouble, Grilled Onion Cheddar Burger, Premium McWrap, Filet-O-Fish, and a large fry—or 20 McChickens.

The average price of a soup and salad at ROC-approved restaurants was nearly $24, meaning vegetarians are also not immune from the effects of a higher minimum wage. Some people can afford the luxury of eating out at a restaurant that they perceive to be “taking the high road,” but many working families and young people, those whose interests worker centers claim to represent, are more concerned with finding an affordable meal.

Worker centers will stop at nothing in their union-funded efforts to organize fast-food workers. They lie with statistics to demonize the restaurant industry and apparently think $20 is an appropriate price for lunch. In the midst of the expected press coverage of their protests on April 15, it is important to keep worker centers’ real motives in mind, which are protecting union bosses—not fast-food workers.