If you Google “I’m not a feminist, but…,” you will find many articles with lists of famous disavowals of feminism, ranging from Katy Perry (who later recanted after her divorce) to Sandra Day O’Connor. But Google doesn’t do the longevity of the phrase justice. I’ve come across it in research back to the 80s when feminists were just as exasperated with movement defections as they are now.

For decades, this “but” has annoyed feminists because they see wildly successful women, who obviously benefited from feminist achievements in the workplace, shun the label. As the list of famous not-a-feminists grows, popular feminist reaction has moved from incredulity to anger to where it currently rests: instruction.

In the latest high-profile disavowal back in April, Shailene Woodley, the lead actress in the “Divergent” franchise and “The Fault in Our Stars,” declared feminists shamed her for not knowing what feminism is about. (See, for example, “Shailene Woodley’s Definition of Feminism is Really, Really Problematic” or the subtitle for another article: P.S. Feminists don’t hate men.) But the actresses are better-informed than the scolds, who usually quote one of the many versions of “feminism is the radical notion that women are people and people are equal.” Rachel Held Evans opened a recent post, “We Need Feminism…” with this inaccuracy. This is lovely sentiment, but actions speak louder than words.

In practice—and practice is what the refusers pick up on—contemporary feminism neither is nor was about simple equality. In practice, it is anti-domestic, anti-men, and frankly anti-woman. And if declared feminists bothered to look back and examine their own movement as critically as they do young starlets’ statements, they would find a history radically different from the notion that “women are people, too.”

Who Read ‘The Feminine Mystique’?

I will start with anti-domesticity, because the story about how feminists can believe feminism isn’t anti-domesticity provides some illuminating background for other feminist confusion.

No professor ever assigned “The Feminine Mystique” to me, but I read it in my mid-20’s when I realized how poorly a BA had prepared me for American intellectual debate. (Some of that was my fault. I wasn’t always a motivated student.) The anti-domestic language of Friedan’s book turned me off so that I slammed it shut before reading the one decent chapter, the epilogue, “A New Life Plan for Women.” I reached for Simone de Beauvoir, which was worse. To be a feminist, it seemed, one couldn’t be a traditional woman and one had to act like man. Those did not appeal to me. (I spent the next few years as an Objectivist, but that is another story.)

For years afterward, I got incredulous and defensive every time someone claimed feminism was about choosing the life we wanted, even if it was a traditional life. Eventually, I honed my rebuttals, adding references to modern anti-domesticity scholars like Linda Hirshman of “Get Back to Work” fame, but I did not discover the source of the problem until feminist blogs celebrated the 50th anniversary of “The Feminine Mystique” in early 2013.

I was reading Slate in bed, as one does. (No? Just me?) They ran a series by some of their more prolific female writers who admitted they had never read “The Feminine Mystique.” My husband noticed my agitation—it was hard to miss—and when I explained he asked, “Isn’t Friedan one of the foundational writers of modern feminism?” I sputtered, “One of?! Try THE foundational writer!”

Even if Friedan fell out of favor later—and she did, for arguing against the anti-motherhood and anti-male mood of the movement in the 70s, in fact—her book had such an impact on the women’s movement in the early 60s, the Second Wave, it should be required reading just to understand the mood and motivations of the movement. Surely some feminists were students of history and knew to study popular contemporaneous works to understand Something Past. I thought the Slate series had to be an anomaly. It wasn’t.

The Network of Enlightened Women hosted a book blog, but NeW is an organization of conservative co-eds. I expected that they would read the book. The Guardian was having a reading book club because few of their writers—not students, professionals—had read it. I began to wonder if anyone but conservatives read the book after about 1970. So I looked to the big thinkers such as Stephanie Coontz, who wrote the retrospective on Friedan’s book. From the intro of that retrospective, “A Strange Stirring”:

I was certain that rereading this groundbreaking book would be an educational and inspiring experience…. After only a few pages I realized that in fact I had never read The Feminine Mystique, and after a few chapters I began to find much of it boring and dated…. It made claims about women’s history that I knew were oversimplified, exaggerating both the feminist victories of the 1920s and the antifeminist backlash of the 1940s and 1950s.

The Amazon reviews were almost as “good.” The first one at the time:

I am a young professor of sociology teaching classes on gender, marriage and social change — and I have never read Betty Friedan’s The Feminist Mystique. Like many women of my generation, I thought I had. I must have, I told myself. Perhaps in college? No. And it turns out that very few of my well-educated feminist-leaning friends have either.

They didn’t read the source material.

All the arguments that feminism isn’t against domesticity—they are false assumptions, wishful thinking. And until recently, when delayed motherhood collided with aging parents and a little caregiving became unavoidable, did these feminists begin to feel the forces of anti-domesticity, often with little curiosity about how the forces arose or how they themselves cultivated them. If something isn’t working well for women, then reflexively and uncritically, they blame the patriarchy.

Everything is sexism, when it isn’t. And pop feminists assume they only need defend the label from anti-domesticity, when they really need to take it back.

The Sexist Question: ‘Can Women Have It All?’

In 2012, Gloria Steinem complained that the Have It All question was a “bullshit” question because no one ever asked that question of men. It’s true. Society doesn’t often ask that question of men, but not because of sexism.

Women ask about having it all because they were told they could have it all…by women like Steinem. The old glossy women’s magazines are full of have-it-all glamour, declaring that women could easily have it all without men. “Steinem did not actually coin the “A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle” quip, but she got the credit for it because it succinctly represented her preaching and the mood of the time. Women didn’t need anything but the old rules and the old men to get out of their way. Each woman was an island unto herself, a self-contained unit of success. Eventually, all of those things we told women back in the 60s to boost their confidence and get them out in the world became the standard by which we now demand singular performance from women.

Check the commentary in many of the lauded feminist pop culture franchises, most recently “Divergent,” “Frozen,” “Maleficent,” etc. Characters get the feminist seal of approval when they are separated from any sort of partnership with men. Having it all doesn’t count unless we are doing it without men.

Men, on the other hand, didn’t have some masculinist movement telling them that they could have it all, much less that they had to do it all on their own. Nor would they have been as receptive if they had. Unlike girls who tend to engage in pretend play in which they are the princess, then the chef, then the teacher or the pupil, all in the space of an afternoon, boys tend to also play games with rules, even if they’ve made them up by consensus. The boy who isn’t fast learns to hit the ball harder or to catch. They train each other in tradeoffs. The rules don’t bend. The boys adapt to the world the way it is. (I host large parties and play dates often. This plays out in my yard, every time.)

Asking women if they can have it all isn’t sexism. It is an aspiration that women who should know better foist upon women who don’t.

‘Better Late Than Ever’

Earlier this year, Tanya Selvaratnam published “The Big Lie,” a book about her personal experience with infertility and how prevalent it is. While lamenting that a sex education hyper-focused on avoiding pregnancy left her, an Ivy grad, with little idea how to get pregnant, she does not blame feminism. She mentions how feminist insistence on delayed childbearing might account for the contraception-focused sex ed that ultimately failed her, but she claims “No one told us not to become mothers while pursuing our ambitions. Rather they focused on telling us what else we could do.”

No one told women not to become mothers while perusing our ambitions? Here’s a tiny sampling of feminist thought from The Washington Post, November 1979:

Summers is one of an increasing number of women who are becoming first-time mothers after age 30. The proportion of women ages 30 to 34 having a first child increased by nearly 36 percent from 1970 to 1977, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

‘Last year alone, about 80,000 women between the ages of 30 and 49 gave birth for the first time,’ writes Terri Schultz in ‘Women Can Wait: The Pleasures of Motherhood After Thirty.’ ‘Many women are increasingly aware that, for them, motherhood is better late than ever.’

Effective contraception, longer lifespan, smaller family size, the feminist movement and affirmative action in employment for women have contributed to the trend, according to Wellesley College psychologists Pamela Daniels and Kathy Weingarten, who are compiling their research into a book, ‘Sooner or Later?’

‘Today, increasing numbers of middle-class women are graduating from college fully intending to combine parenthood with work of their own,’ they write. ‘So that they can have both, and in order to make some kind of career commitment first, many are planning to postpone parenthood.’

“Better late than ever.” That’s a catchy little phrase used so glibly then and likely not well received today by women hopped up on hormones and hopeful for a good harvest. (That’s what egg retrieval is called, “harvesting.”) Our elders knew exactly what they were telling us to risk. Now, waiting until after 30 seems almost quaint.

Many have tried to tell the truth, but the contraception-focused sex ed that Selvaratnam blames for failing her and many others results directly from feminist worry that telling women about biological clocks pressures them into motherhood. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine faced effective backlash from feminist groups over a decade ago for a fertility public awareness campaign precisely because feminists saw it as sexist pressure. And I assume Selvaratnam knows of, but just doesn’t mention, the biological clock book that came before hers, Sylvia Ann Hewlett’s “Creating a Life,” the 2002 talk of the book world that didn’t sell. Like that book, despite extensive coverage, Selvaratnam’s book didn’t sell very well, either. Women engage in some serious willful blindness about fertility.

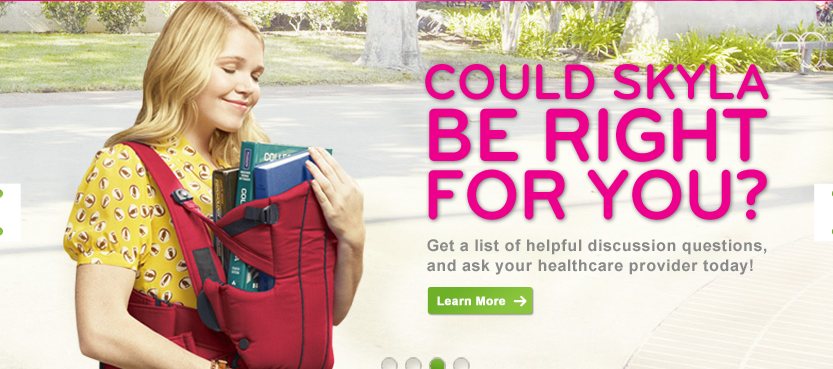

Find more recent admonitions to delay motherhood in these IUD ads currently appearing in women’s magazines.

Most of the young women I know now were told by mothers, teachers, and other women not to even consider marriage in their 20s, much less motherhood. Younger wives and mothers form support groups to deal with the stigma. In practice, motherhood is for your late 30s. Better late than ever.

Feminism And Men

Of all the little lies feminists tell themselves about the movement, that feminism isn’t anti-male has to be the most difficult to sustain. There are just so many examples of anti-male practices, I find it difficult to choose one to highlight. Historical: Pop back up to the section on Steinem and her fishes and bicycles and ponder how that phrase ever became popular. Typical: Treating men as unmotivated dunces? I’ve covered that, twice. Treating husbands as children in the hands of a smarter, more competent woman? Matt Walsh had a great post on that. Internal: Karen DeCrow, first president of the National Organization of Women, was ostracized by the movement for advocating for men. Legal: Lack of basic defendants’ rights on college campuses and unequal enforcement of Title IX? The Wall Street Journal has done some great work covering those. Popular: Feminist tendency to overlook a lot of contradictory evidence to praise any movie that pits women against men (up to and including movies that end in joint suicide of the women)? Those I’ll write more about another day.

Illustrative stories all, but as a mother of a 10-year-old son, the current travesty commanding my attention is school and drugs. By lessening adults’ patience for children through discouraging experience with children, by destroying the communal structure that used to support childrearing, and by tailoring school to bolster young girls, feminism has led the way toward medicating children, or really boys, into submission.

“At least” 75 percent of ADHD prescriptions are to boys. Actually, the 75 percent floor is a Canadian statistic. It is difficult to find recent and straightforward sex comparison statistics in the United States. It is as if we want to avoid seeing exactly how lopsided our drug practices are. The Centers for Disease Control reported last year that ADHD diagnoses are rising and that boys are diagnosed at about twice the rate of girls. And it gets worse. A CDC official announced recently that doctors are prescribing the drugs to toddlers, well outside of the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines. If the CDC announcement included data breakdown by sex, the New York Times did not mention it, instead blogging about the class implications of the study. (Most of the off-label prescriptions were to children on Medicaid.) But if the proportions hold, then boys disproportionally face treatments that will stunt their development.

Feminist can talk all they want about how the movement is about freedom, equality, and choice. But everyday experience molded by what feminism does feels more like naiveté, loneliness, and cruelty. The young and powerful women who reject the title “feminist,” that’s what they notice. Feminists say one thing, but do another.