It’s a well-worn lament heard from many American pulpits: there is just as much divorce inside the church as there is outside. But if pastors and their flocks are embarrassed by divorce equality, then recent findings published in American Journal of Sociology are likely to give them an even nastier shock: conservative religious beliefs are not only failing to uphold the marriages of religious conservatives, they are actually destroying their neighbors’ marriages too.

The recent study “Red States, Blue States, and Divorce” makes a straightforward claim: “Conservative religious beliefs and the social institutions they create, on balance, decrease marital stability through the promotion of practices that increase divorce risk in the contemporary United States.” For example, by discouraging premarital sex and encouraging early marriage, conservative religious institutions unwittingly contribute to high divorce rates, the authors argue. Their analysis finds that “communities with large concentrations of conservative Protestants actually produce higher divorce rates than others.”

Kayla and Adam are a young married couple interviewed as part of The Love and Marriage in Middle America Project, a four-year qualitative research inquiry into the relationship and family formation of 75 working class young adults. At first blush, they seem like poster children for the “Red States, Blue States” research. They pushed up their wedding date by a year because Kayla’s Baptist parents disapproved of their cohabitation, and because their pastor refused to marry them unless they stopped cohabiting. Shortly after their wedding, Kayla discovered Adam was abusing his prescription medication. A few years later, he got arrested for overdosing on heroin. Then, Kayla found a love note from Adam to another woman. And just like that, it was over.

Now Kayla wonders if she could have avoided divorce by cohabiting and delaying marriage—exactly what her Baptist parents and pastor advised her against.

Kayla and Adam appear to illustrate what writer Michelle Goldberg concluded about the “Red States, Blue States” research: “conservative family values don’t work to conserve actual families.”

The Story Doesn’t End There

It’s tempting to leave the story with Goldberg’s ironic twist, but findings from four years’ worth of interviews with couples like Kayla and Adam, combined with our recent analysis of some of the best survey data available on the lives of young Americans, paints a more complex story of religion, marriage, and divorce in young America. That story has implications for strengthening marriage in working-class communities, where research shows divorce and single parenthood is most common.

Here’s the key nuance: while religious affiliation makes no difference when it comes to divorce, religious attendance does. The “Red States, Blue States” research fails to make this distinction.

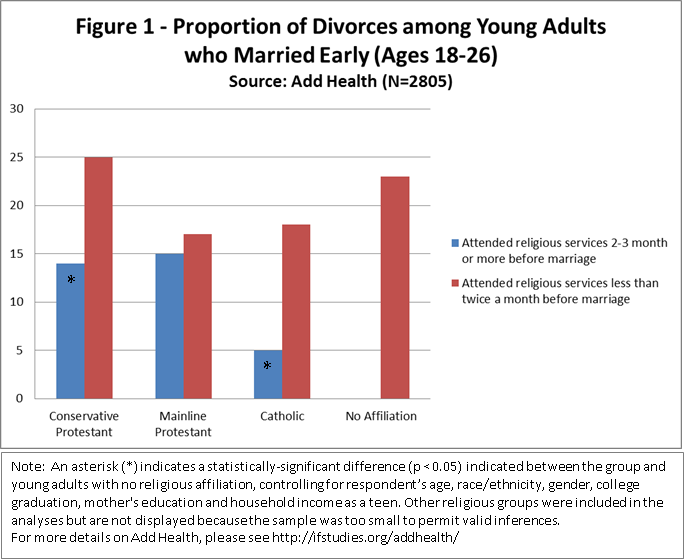

The strongest evidence of the marriage-stabilizing power of religious participation comes from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), a federally funded, nationally representative sample of young adults. Our recent analyses of Add Health reveal that attending church regularly during young adulthood appears to significantly decrease the risk of divorce, even for those who marry relatively young.

Of the 2,800 young adults represented in Figure 1, all married early by American standards, from ages 18 to 26. Those who divorced (about 20 percent of this sample) had relatively short marriages. According to the “Red States, Blue States” research, it is precisely among this divorced group that you would expect to find lots of conservative Christians. But, as Figure 1 shows, the two groups likely to have the most conservative family values (high-attending conservative Protestants and high-attending Catholics) are also least likely to have divorced.

In multivariate analyses, high-attending conservative Protestant young adults have 34 percent lower odds of divorcing than do the non-religious, and high-attending Catholic young adults have 76 percent lower odds of divorcing than do the nonreligious. (Other religiously conservative groups, such as Latter Day Saints or Muslims, may exhibit similar “divorce-proofing” patterns, but the sample size is too small to distinguish these groups.)

It appears, then, that conservative family values do “work,” but only when those values are regularly reinforced and supported by integration into a local religious community.

The Nominally Religious Most In Danger

Nominally religious young adults are in a vulnerable position: they are religious enough to be pushed into early marriage, for instance, but, lacking the social support mediated by an in-the-flesh religious congregation, they don’t reap the benefits of involvement in a religious community. Instead, religion may become a source of conflict. Like Kayla and Adam, most of the working-class, divorced individuals interviewed in the Middle America Project either reported pressure from religious relatives to marry earlier than they would have liked, or reported conflict because one spouse was not on board with the other spouse’s religious involvement.

In other words, a little bit of religion can be a bad thing for marriage.

Given this, while Kayla and Adam identify as Baptist, it’s not surprising that their religious affiliation did little to protect them from divorce. Their actual church attendance was sporadic, and both expressed ambivalence about conservative religious beliefs, particularly those concerning sex and marriage. “I believe there’s a God. I believe in the Bible. I believe in the beliefs, but I don’t exactly walk every line that you’re supposed to walk,” Kayla says.

Kayla and Adam’s attitude toward religion is typical among working class adults, for whom religious attendance is declining. In the 1970’s, 40 percent of high-school-educated adults regularly attended church. By the 2000’s, only 28 percent did.

It’s not as if other communities have stepped in to fill the void. The story of decline is also true for membership in a nonreligious civic group: whereas during the 1970’s 71 percent of high-school-educated adults were members of a civic group, by the 2000’s only 52 percent were.

The upshot is that increasingly unaffiliated, working-class young adults struggle to find the support needed to sustain a marriage. Adam says that while his family strongly supported his marriage, his friends did not: “They don’t share the same religious beliefs. They’re not married, and they’ve been in the same relationships for five or six years. They just say that I got married too soon and that I didn’t know what I was getting into.”

Furthermore, with high divorce rates among the working class, families—traditionally, an important source of support and guidance—now typically include relatives who transmit cynical attitudes about marriage to the younger generations. “Marriage ruins relationships” and “men suck” were refrains commonly heard from young adults we interviewed.

The result is that more married couples, especially those who marry young, are on their own. As Kayla says, “You need support from your friends and family. Otherwise, you’re pretty much on your own. And you can’t do stuff like [marriage] on your own.”

Religious Communities Can Help

As the Add Health data suggests, at their best religious congregations can actually help to provide some of this much needed social support, thereby lowering regularly-attending young adults’ risk of divorce. As Robert Putnam noted in his classic, Bowling Alone, “Faith communities in which people worship together are arguably the single most important repository of social capital in America.”

Young adults interviewed for The Middle America Project mentioned a number of ways they encountered support from religious congregations. One husband reported that he learned many of his prudent financial practices at a church-sponsored Dave Ramsey class to which his religious father-in-law referred him. Another husband pointed to his church’s encouragements to “date your spouse” as the source of inspiration for him and his wife’s frequent dates.

Church provided social support for Gavin, a 23-year-old newlywed and young father of two also interviewed for The Middle America Project. When Gavin struggled to find work, a church friend who owned a painting business offered him a job. When he was laid off during the recession, another church friend led him to a better job in the shipping and receiving department at a pharmaceutical company.

Gavin exhibits a double integration with his faith community. His supportive church network helps with marriage advice, theological reinforcement, and practical help like finding a job. And he has internalized the theology behind the conservative marriage norms—he believes that marriage is a reflection of Christ’s love for the Church, and that divorce is an “impossibility” so long as he and his wife “put Christ first”—which gives him intrinsic motivation to follow a set of rules increasingly out of step with the wider culture.

So while a little bit of religion can be a bad thing for marriage, stories like Gavin’s help us to understand why the survey data shows that regular religious practice significantly reduces the risk of divorce.

In an era in which good marriages seem increasingly out of reach for working-class young adults, our findings about religious observance and early marriage offer a glimmer of hope. Integration into supportive communities can help stabilize fragile young families. For working-class young adults who marry young, the difference between mere religious affiliation and deep involvement in the life of an actual congregation might be the difference between the death of a marriage and “‘til death do us part.”

Charles E. Stokes is assistant professor of sociology at Samford University and a senior fellow at the Institute for Family Studies. Amber Lapp and David Lapp are research fellows at the Institute for Family Studies and co-directors of the Love and Marriage in Middle America Project.