Ta-Nehisi Coates’ essay, The Case for Reparations, has been published to great fanfare. By journalistic standards it is a massive tome which does not deliver on the promise of “groundbreaking” original content. Nevertheless, in light of the noisy discussion the article has generated, it is worth examining the article’s actual content and considering its merits.

On my assessment, the essay accomplishes three things, one good, one bad, and one ugly. His argument for the contemporary relevance of historical racism is arresting and thought-provoking. This is the best part of the piece. The argument for reparations is unpersuasive, but perhaps (as Kevin Williamson has suggested) instructively so; by spelling out the argument for reparations Coates illustrates how weak it actually is.

Regrettably, much of the essay is really devoted to honey-tongued pandering to the pathologies of the left. This is unfortunately the part that most thrills Coates’ ecstatic admirers.

The Contemporary Significance of Historical Oppression

Coates has a gift for affecting more nuance than he really offers. It’s impressive how he manages to weave such elegant circles around such a brutally simple argument. In some ways this is irritating, but there are upsides. The eddies and side channels are really the most interesting part of this piece.

He takes us on an extended tour of black history, with the goal of establishing three things. First, racism was a very, very bad thing which did grave injustice to large numbers of black Americans. Second, America’s current prosperity was to a great extent made possible by slavery and other forms of exploitation. Third, black Americans today are struggling in a myriad of ways, and this is a fairly direct consequence of the injustices they have suffered. Hence his final conclusion: America owes them.

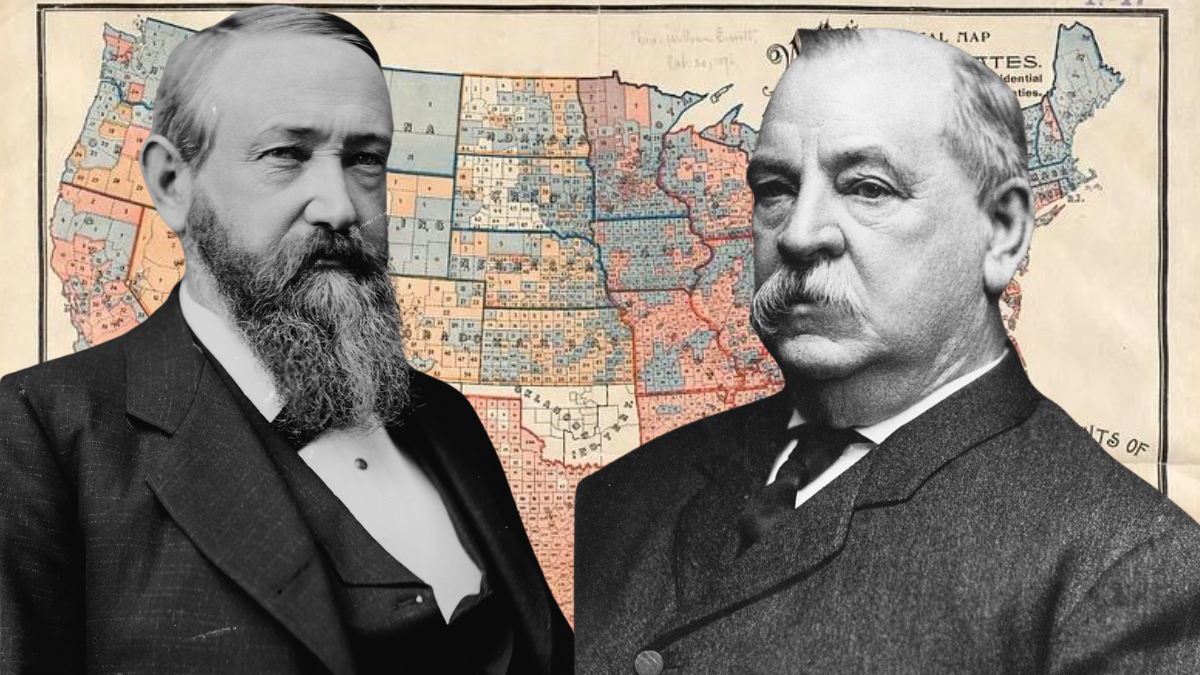

That slavery and racism were gravely unjust is obvious, but the essay still provides some historical perspective that may be useful. We are reminded that the legacy of obvious and deliberate oppression really can’t be written off as ancient history; there are plenty of people alive today who were once at the front lines in combatting racism, or in perpetuating it. Looked at against the backdrop of history, those wounds are still quite fresh. Even if we restrict our narrative to the history of our own relatively youthful country, the unhappy truth is that on racism has been a significant phenomenon for, unfortunately, the majority of our history.

Given how juvenile and peevish our modern-day discussions of race often become, it can be useful to dip back into that history once in awhile. In our eagerness to move on from the mistakes of the past, we can sometimes become a little impatient. It’s fairly normal for a society to require an extended period of time to fully come to terms with such a grim history of enslavement and oppression. Realizing that, we should try to engage erroneous liberal arguments with good humor.

And in fact, Coates is fairly persuasive in his efforts to link the struggles of contemporary black Americans back to historical oppression. I say “fairly” because his argument is predictably incomplete. On the plus side, he does convict New Deal progressives of their complicity in the segregationist agenda of Southern Democrats, which allowed black Americans to be herded into segregated neighborhoods where became deeply entrenched in poverty. It’s good to see that history recounted in a high-profile publication. Later progressive policies (from the 1960’s and beyond) receive gentler treatment, which is unsurprising but also unfortunate; these are the policies that are most directly blighting the prospects of the poor today.

Anyone familiar with Coates’ work would have seen this coming; he has established in the past that he is unwilling to condone any criticism of contemporary black culture until historical grievances have all been adequately addressed. This of course is terrible news for the urban poor, since it disallows most of the conversations that would offer some chance of making their lives better. Still, conservative readers who are already familiar with the part of the story that Coates omits may find it enlightening to reflect on the extent to which the ravages of the Great Society were themselves a not-so-indirect consequence of historical racism. Although the grim effects of welfare dependence and widespread social collapse are now manifesting themselves across poorer demographics nationwide, few were hit as quickly or as catastrophically as the black community. There were reasons for that.

Owing not just to slavery, but also to twentieth-century discrimination, black Americans were in a particularly vulnerable position when Great Society reforms were instituted. Thanks to centuries of enslavement and oppression, they were already poor, ill-connected and segregated into mostly-black neighborhoods. It’s hardly surprising that the winds of cultural destruction wreaked particular devastation in their communities. Progressives don’t deserve to be given a pass for their ill-conceived policies, but it’s still valuable for conservatives to remember that racism is still relevant to the economic and cultural struggles of black Americans today.

The (Unpersuasive) Case for Reparations

It’s reasonable enough to argue that impoverished black Americans deserve particular solicitude from their compatriots. But in actively calling for reparations, Coates wildly overshoots.

He tries to generate sympathy for his cause by likening our legacy of historical oppression to a massive load of credit card debt, suggesting that overcoming the racist views of our forbears (assuming that we have) is merely analogous to bringing profligate habits under control. It doesn’t eliminate the debt. Reparations must be paid before we can truly have a clean historical slate.

It’s true, of course, that we can’t make history right just by eliminating racism today. We can’t make it right at all. That’s the first point. The second is that the living always inherit a complicated legacy from the dead. It’s not an argument for reparations. It’s just a regular part of the human experience.

One major problem with Coates’ essay is that he says very little about reparations as such. His focus is almost entirely on documenting injustices done, and instilling an appreciation for black Americans’ contributions. As interesting as that might be, it sheds almost no light on the weirdness of trying to make up for centuries of oppression through one grand act of expiation. History is full of injustice, and the fortunes of particular individuals are always affected (in good ways and bad) by elements of their own background and family history that are beyond their control. That isn’t per se a defect in our own society. It’s how the world is.

Black Americans may (on average) be born into less advantaged circumstances than their white compatriots for historically explicable reasons, and we may reasonably lament that fact. We may regard it as an act of patriotism to help our struggling compatriots improve their lot. But there’s a reason why it isn’t standard practice to litigate inter-generationally on behalf of enormous, loosely-defined groups of people. It’s a process that would never end, and the effort would itself inevitably precipitate further injustice that would then call for further redress. That is why, as Williamson persuasively argues, we have to consider present-day individuals as individuals, and leave generalized historical injustice in the past.

Although he never provides an explicit discussion of the morality of reparations per se, Coates does seem to recognize that he needs to mark this particular historical injustice as distinctive or exceptional in order to justify such an unusual course of action. He tries to draw such a distinction, but it’s not compelling.

Coates suggests that there is a deep causal relationship between America’s present wealth and the historical oppression of black Americans. Perhaps it’s true (he might suggest) that we all, in a contingent sense, owe our present existence to a variety of historical circumstances. We can’t ask the law to provide redress every time those prove personally disadvantageous. But, suppose our nation’s present prosperity is, in some deep and necessary way, predicated on injustice. Might that give us a more compelling reason to offer reparations to the exploited, or at least to their present-day, still-disadvantaged descendants? Might it really be necessary to do so, in order to enjoy our goods and freedoms without guilt?

The argument has great emotional appeal, because it is satisfying to suppose that benefitting black Americans might be seen as an act of justice and not of mercy or (worse) pity. There’s nothing patronizing about reparations if they can be seen as “back wages” due for services historically rendered. And, if today’s prosperous Americans are still reaping long-term benefits from those services, it’s not really unfair to ask them to pay the tab.

Conceptually it seems neat, but the argument really isn’t sound. First and most importantly, it’s just not the case that thriving democracies require a foundation in slavery and oppression. In fact, comparing the economic and political fortunes of countries or regions that relied heavily on slavery (such as Brazil) to regions that didn’t (such as Great Britain or the American north), one could quite plausibly make the argument that slavery is economically disadvantageous over the longer term.

Even mentioning this in the context of Coates’ hideous account of grave injustices done to black Americans (families broken, women raped, children lynched) seems almost irreverent, but what this really shows is the complete irrelevance of the entire line of discussion. The evil of slavery could never be justified by any economic or political benefit we may have derived from it, and no apology will be sufficient to right the wrong. By the same token, though, slavery is not written intrinsically into our economic or political DNA. We needn’t perform special ablutions in order to expel the demon; it is enough to repudiate it as completely as we can, and to endeavor to live up to higher American ideals.

The Moral Importance of Being American

Given the almost ludicrously effusive praise that has been lavished on Coates (documented here), one would assume that he must be extraordinary in some way. He is. Unfortunately, the part of the essay that has liberal souls quaking is really its most insidious element. Coates excels at giving effete, mostly white, mostly over-educated liberal progressives a sense of historical momentum. Few things are more satisfying to the progressive, or less useful to the struggling poor. In this instance, Coates has set hearts on fire by assuring his readers that there are still a few morsels of consciousness-raising sweetness left in the race-relations goodie box.

I have written before about the vitally important role the Civil Rights movement plays within the progressive psyche. For liberals, the desire to re-experience the satisfaction of racial rapprochement often takes priority over all manner of sound policy considerations; predictably, the (disproportionately black and Hispanic) poor pay the heaviest price for this selfishness. Liberals are delighted with Coates because he has assured them that another thrilling episode remains unwritten in the Civil Rights narrative that they so dearly love.

However much one admires the historical segments of his essay, it’s impossible not to smirk when Coates gets around to mentioning that the “reparations” he calls for might not really involve money so much as changed paradigms and raised consciousness. These, of course, are favorite liberal themes. Fretting about triggering and hash-tagging is much more satisfying than sorting out grubby, plebian problems like scarcity and sin. But here especially, the call for consciousness-raising is simply foolish. If a national conversation about race could fix the problems of urban poverty, it’s safe to say that those problems would be solved.

In my more charitable moments, I can actually believe that the liberal obsession with race has some roots in a genuine thirst for justice. Oppression is ugly and its effects still haunt us; liberals yearn to see the nation made new through one grand act of expiation. Through the collective will of the American people, the lingering scars of racial hatred should simply be erased and the field leveled; the shadows of the past should be vanquished through one great outburst of light.

I can see the appeal. But it isn’t possible, and the dream begets suggestions that are not just impracticable, but actually offensive. This is clearest in the final portion of Coates’ essay, in which he uses the precedent of Germany’s post-World War II reparations to Israel as a model for the kind of gesture he has in mind. He doesn’t seem to see how utterly inappropriate this comparison is.

This is true, in the first place, for practical reasons. Money can never really atone for murder, but at least the Holocaust was a recent, discrete event of limited duration. To some extent the losses could be counted, and actual survivors compensated.

Even more important, though, is the fact that these reparations were paid from one nation to another. Germans had harmed Jews, so Germany paid Israel. The line between oppressor and the oppressed was, if not exactly glowing, at least bright enough to give everyone some sense of justice. No such line exists in the case at hand.

Black Americans are Americans. The history Coates reviews is part of our shared history, just as much as the Constitutional Convention, the Louisiana Purchase, Pearl Harbor or Woodstock. This heritage is rightly a source of pride and of shame to every citizen, but there is no way that We the People can collectively compensate a broad segment of our population for wrongs perpetrated against the dead. Even attempting to do this would imply that certain citizens are “victims” of history rather than its rightful inheritors, with the obvious further implication being that they have a lesser share of that patrimony. This seems to me like a grave insult that no patriotic American would want to accept.

Coates’ suggestion, therefore, is not merely impracticable and pie-in-the-sky. It is injurious to the integrity of our society, and especially to the honor of those he claims to champion. No reparation could truly make up for past injustices. They will stand forever as a stain on our history. At the same time, there can be no better repudiation of those sins than the acceptance of black Americans, neither as an underclass, nor as a protectorate, but rather as full-fledged citizens of our nation, with all the rights and responsibilities that that entails. We cannot “owe” them any more without effectively giving them less.

None of this is to say that we should turn a blind eye to entrenched poverty and social collapse. We should in every way be assiduous to find solutions, searching constantly for more effective ways to promote the thriving of our most disadvantaged citizens. But we should do this as Americans, eager to build a more just and more prosperous nation for all of our compatriots. Only that way can we heal the scars of dark ancestral sins.

Rachel Lu teaches philosophy at the University of St. Thomas. Follow her on Twitter.