Understandably, many fans in small market cities are frustrated by the inequity of professional sports. There is a remedy – or call it more of a tradeoff.

You can always move your family from the manageable low-taxed mid-sized city’s suburb you live in to one of the most congested, expensive places on earth. Buy a 500-square foot $1-million apartment. Send your kids to an abysmal public school system. Pay property taxes that will top your formerly impressive salary. Overpay for cable and/or buy exorbitantly priced tickets. And then feel free to root for an overpriced team that wins occasionally.

But stop blaming the Yankees for your cheap, local franchise, and be happy that your team is subsidized by giant revenue-generating clubs in the cities you avoid.

The Evil-ish Empire

When the Yankees signed catcher Brian McCann last week, the New York front office released a statement that said, in part: “The singular and unwavering desire of this organization is to construct a team each and every season designed to play meaningful baseball deep into October.”

This is the charge of all professional baseball franchises, is it not? Yet, whenever the New York Yankees sign a free agent, as they recently did Jacoby Ellsbury, millions of purportedly sane people erupt into a perfunctory orgy of hate, losing any capacity for rational thought. It’s like an Occupy Yankee Stadium rally on Twitter. Where’s the fairness, the parity, and the equality? Reporters, television broadcasters and columnists around the country start dropping the same inane jokes about Yankees spending. Mike Lupica pulls out the column he’s been writing for the last 30 years.

Part of this is, no doubt, a national distaste for New York. But the point sportswriters make is that the Yankees are killing baseball. I’ve been hearing this my whole life. And still, baseball survives. It survived “Catfish” Hunter, Reggie Jackson, Dave Winfield, Jack Clark and Danny Tartabull. And the Yankees survived Carl Pavano. Me? I couldn’t care less if a player signs for $138 million or $250 million, for 10 years or 25 years or 2 years, because in the end, I only wish the Yankees were as ruthless as everyone alleges.

The disheartening truth is that while the Yankees spend plenty, they aren’t as reckless as you think. Last season, for instance, the New York roster didn’t feature a single prominent free agent. Though many high-paid players are on the payroll, some were legacy contracts (Derek Jeter, A-Rod), which are as much about business as baseball. Since 2009, the Yanks haven’t been genuine players on most big names – Prince Fielder, Josh Hamilton, Albert Pujols, Carl Crawford and so on.

In fact, the Yankees have yet to submit to the demands of their second basemen Robinson Cano (somewhere in the vicinity of $260 million over nine years if you believe reports). They could. Easily. New York is still, if reports are true, trying to bring their payroll under $189 million this season, the number they need to hit to reset the luxury tax rate and get under the salary cap. If Alex Rodriguez’s contract is scratched from the payroll, and there’s a chance that might happen, it’s plausible that they can do it and fall beneath the Dodgers for the second time in three years.

As it stands, the Yankees payroll looks worse than it really is. Vernon Wells — the kind of player, granted, that only teams like the Yankees could afford as an injury replacement — is the second highest paid Yankee. But the Angels paid $29 million of $42 million on that terrible contract. Similarly, of the $24.5 million Alfonso Soriano (the fourth-highest paid Yankee) made through the end of last season, the Cubs paid $17.7 million and the Yankees took on $6.8 million. Soriano is scheduled to make $18 million next season, and New York will reportedly pay only $5 million.

In recent years, the Yankees have been no worse in making bad free-agent decisions than the Dodgers or Angeles or Red Sox or Cubs. And the contracts we’ve seen elsewhere during that time have been enormous — often long-term deals for player on the wrong side of 30 –that have contributed as much to the upward spiraling salaries as anything the Yankees have done.

Markets in everything

Which brings me to default reaction of most fans: horror at the size of player contracts.

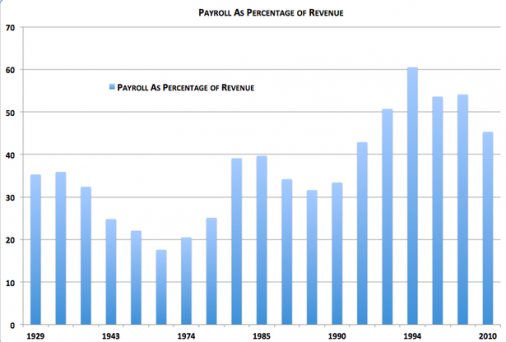

Are the Yankees – or any big budget teams — overpaying players? I suppose that depends on how you look at things. It’s worth remembering that in 1994 Major League Baseball’s revenues were $1.2 billion, and by 2013 it was somewhere around $8 billion. The trajectory of salaries keeps pace with those revenues (though it would only take a couple of Kansas City Royals championships to put an end to that sort of growth.)

Matthew O’Brien at the Atlantic, in fact, made a strong case that players are actually being underpaid. He compiled a handy chart that illustrates average payroll as a percentage of revenue going down over the past few years.

So when the Yankees sign Jacoby Ellsbury — a very good player, but no superstar — for a reported seven-year, $153 million deal, making him one of the highest players in baseball, people can’t stop talking about how absolutely crazy it is. The Yankees need players to be competitive, and in this marketplace Ellsbury is probably the second best position player available. He stole 52 bases last season, was caught four times and is a career .297 hitter, with a career .350 on-base percentage. He’s a top-shelf post-season performer. He’ll likely get the second biggest contract after Robinson Cano. There’s nothing unreasonable about it.

And for the Yankees (a business), and MLB (also a business), this isn’t only practical on the field, it’s necessary elsewhere.

According to Bloomberg, New York Yankees are worth $3.3 billion, making them baseball’s most valuable franchise.

The Yankees are first in team revenue: $570 million

First in gate receipts: $265 million

First in concessions: $53 million

First in sponsorships: $84 million

First in media rights: $158 million

The Yankees recently sold nine percent of YES Network to News Corp. for $420 million — valuing their own remaining stake at more than $930 million. They generated $215 million more than the Dodgers, who had the second highest payroll last year — the difference being more than the average revenue of the average major league team. The Yankees made more than $340 million dollars than the Washington Nationals (who sit somewhere near the average).

The team isn’t worth three billion because they waiting for Slade Heathcott to mature in Double-A (though they always have the luxury to sign someone as a placeholder and wait). The Yankees have created a titanic company, which, yes, is aided by their geography but also by sound management and winning. The New York Mets, in the same town, have been unable to generate a similarly profitable or dynamic business for an array of reasons — most importantly, though, because they don’t win. And last year, the Yankees, who are consistently the best road draw in the league, missed the playoffs for only second time in 20 years. The team’s ratings fell by a third and its average attendance fell by 3,000 per game, one of the worst drops in baseball. As revenue goes, betting on Ellsbury and McCann (and, fingers crossed, others) to create excitement for fans is a cheaper proposition than failing to make the playoffs for a second year.

Welcome to the majors

Money isn’t everything in sports. Six different teams have won the World Series in the past decade — which constitutes better parity than usual — some of them won with middling payrolls. But money certainly matters. So it’s curious that so much ire is aimed at teams that play to win rather than teams that don’t.

Take the Houston Astros, who have lowest payroll in the league, spending $26 million on their entire last season – less than the Yankees kicked in with the welfare luxury tax. Those same Astros recently signed one the most lucrative cable television deals in all of baseball.

According to this Forbes piece titled “2013 Houston Astros: Baseball’s Worst Team Is The Most Profitable In History”:

Sixty-four major leaguers make more individually than the Astros’ current 25-man active payroll makes collectively. The New York Yankees pay nine players more than the Astros payroll. Twenty other teams pay at least one player more. And Jason Bay, who is not even on a team, earns more than the all of the Astros, thanks to an old contract with the New York Mets. The Astros are on pace to rake in an estimated $99 million in operating income (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization) this season. That is nearly as much as the estimated operating income of the previous six World Series championship teams — combined.

Some have disputed the story. But at 43-86, the Astros were the worst team in the league. Their highest-paid player made $1.15 million. Now, I realize it’s tough to be a small market club (Houston, being the fourth largest city in the country, and all), but the Astros could easily afford to bring in Ellsbury or Cano. Being that bad is a choice.

The Yankees, too, could easily scale back their payroll and still make a lot of money. Maybe even more. This is what Robert Nutting, who is estimated to be worth over $1.1 billion, does. He owns the Pittsburgh Pirates, a team with the 4th cheapest payroll in the league last year at $66,289,524.

Jim Pohlad is worth estimated to be worth $1.1 billion. He owns the Minnesota Twins, who own the 8th cheapest payroll, $75,562,500 .

Hiroshi Yamauchi is worth $2.1 billion. He owns the Seattle Mariners and shells out $84,295,952, way below the league average.

After all, if you’re only willing to shell out minor-league salaries, that’s where your team probably belongs. Whine about the Yankees all you like, but they’re the least of baseball’s problems.

Follow David Harsanyi on Twitter.