The problem snakes into unlikely corners our world, from presidential elections to the empty houses of alienated relatives. The scope is astounding. Our fraying community ties, oft debated in the context of politics, can be seen everywhere.

I saw them most recently in an article published by The Cut. At the end of her deep dive into the link between estrogen and schizophrenia, reporter Lisa Miller included a heartbreaking anecdote about one of her female sources, 61-year-old Janet, who “lives in a small town surrounded by forest and winding highways.”

Janet had no history of mental illness when, in 2001, she suddenly began hearing voices. Now she lives alone. Writing of a trip to Janet’s apartment for the story, Miller notes, “I have to get home, but I can tell she doesn’t want me to leave.” Here’s more:

She is very lonely, she tells me. Her daughter had just moved to South Carolina, and her relationship to her church community had frayed. ‘Little by little, one by one, the people in my life have all dropped out, and now I’m back to being kind of solitary again. And I don’t like that,’ she says.

Janet sent Miller an email the day after their meeting. So lonely she struggled to sleep, Janet wrote, “I think there is knowledge out there, but I think it’s old, ancient knowledge that has been lost to the generations through the rapid, rapid changes — I’m talking about the past 50 years — and explosions in population.”

“We don’t live the way we used to,” she continued. “We used to live tribally. The tribes could always share. There was a huge close-knit community that could share. I know what we need. I don’t know how to get it, but I know what we need: We need people who understand what is happening to us to sit down with us and explain it. At some level, we could just use someone to say, ‘Okay, you’re 45 years old. You’re perimenopausal. You’re hearing voices. Here’s what’s helped these three dozen other people. Tell me your story.’”

Where is that someone who should be asking for her story? How often do we have the opportunity to be that person? Do we need that person ourselves?

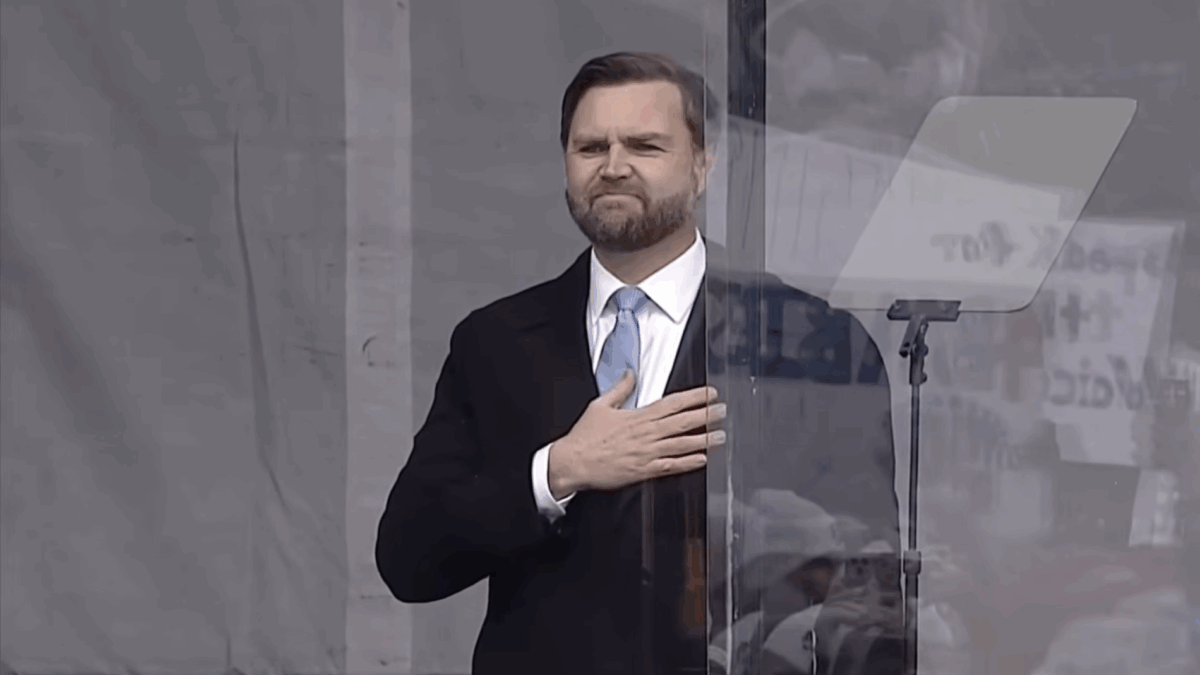

There are many Janets in our country, people longing for the “close-knit community” she mourns, something that once supported a wide swath of us almost by default. Of all things, Donald Trump’s electoral success has precipitated a conversation about this problem in political circles.

Tim Carney of the Washington Examiner, my former editor, is set to release “Alienated America” next month, which will explain crucially why “it’s not the factory closings that have torn us apart; it’s the church closings.” Here’s an excerpt from the book’s description:

The standard accounts pointed to economic problems among the working class, but the root was a cultural collapse: While the educated and wealthy elites still enjoy strong communities, most blue-collar Americans lack strong communities and institutions that bind them to their neighbors. And outside of the elites, the central American institution has been religion.

That is, it’s not the factory closings that have torn us apart; it’s the church closings. The dissolution of our most cherished institutions—nuclear families, places of worship, civic organizations—has not only divided us, but eroded our sense of worth, belief in opportunity, and connection to one another.

Recall that Janet informed The Cut her “relationship to her church community had frayed.”

Weighing in last week on the debate over Tucker Carlson’s provocative monologue, Carney wrote, “it’s not that the ruling class isn’t doing enough for the average guy. It’s that the system set up by the elites isn’t allowing him to live out his life in the way humans are supposed to live: in a family, supported by a community.”

Tim and Janet are essentially talking about the same thing. What strikes me is hearing as much straight from Janet, who manages the stockroom for a chemistry department at “a small northeastern college,” and reached her conclusion not through politics but through a long struggle with schizophrenia. In noting her “frayed” relationship to her church, longing for community, and ultimately lamenting the decline of tribal living, Janet is troubled by the very same pattern.

This isn’t to project politics onto Janet, whose full story I don’t know, or to blame anyone in particular for her plight. It’s really the opposite. The most visible symptoms of this problem may be some of the names in our headlines. But they’re also as invisible as a lonely woman lying awake in an empty apartment at night, so isolated she can’t fall asleep, whose only reliable company is a chorus of unwelcome voices in her own head.