In May of 2011 the average U.S. gas price as measured by the U.S. Energy Information Administration peaked at just over $4. At the end of January, 2018 it was down to $2.72, a reduction by 32 percent. If you are driving the average 1,3476 miles that Americans drive every year, in a 2016 model car getting the average 24.7 miles/gallon, then congratulations: you saved about $700 last year compared to 2011. Factor in everything else you consume that has benefitted from declining oil and natural gas prices — heating your home, airline travel, every product under the sun that contains plastic — and it is reasonable to think that you are saving a couple of thousand dollars compared to six or seven years ago.

Your gain is somebody else’s loss. More specifically, your gain is the loss of the oil producing nations who used to hold the world hostage with their near monopoly on oil and gas production. What has changed? The U.S. oil and gas industry has once again become a factor to reckon with, and our country and the world is a better place for it. And we have one man especially to thank for it: George P. Mitchell, the “father of fracking.”

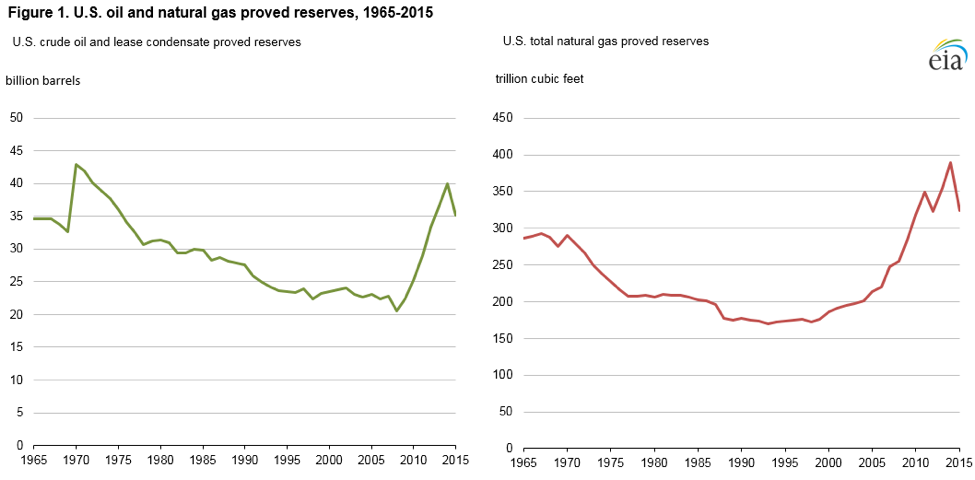

The last decade the U.S. has made astonishing progress in oil and natural gas production, thanks to advances in exploration and extraction technology. Exploration improvements have unearthed vast new reserves of both oil and gas, and extraction innovations — the “fracking revolution,” or more precisely hydraulic fracking advances combined with horizontal drilling — have made more of the reserves economically feasible as shown in this chart of proved reserves through 2015:

(proved reserves are considered recoverable under current economic conditions; the dip in U.S. reserves in 2015 is explained by the low oil and gas prices making certain shale reserves economically but not technologically unrecoverable).

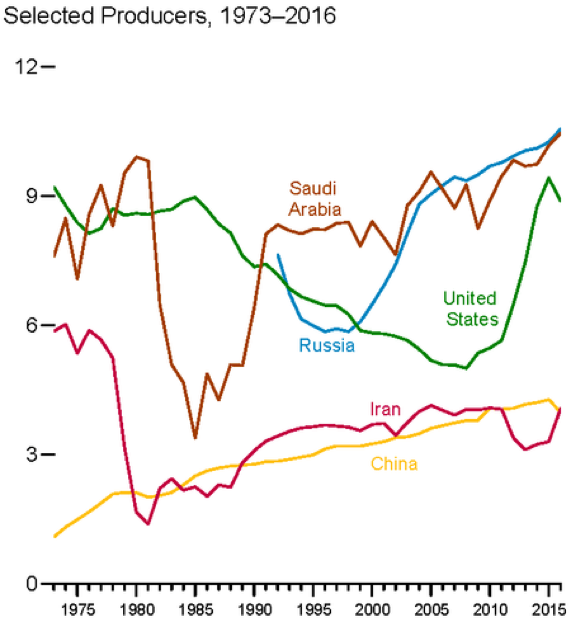

As a result, U.S. oil and gas production has skyrocketed, and the U.S. is now the world’s largest natural gas producer, and on the path to again becoming the world’s largest oil producer:

The fracking revolution went comparably unnoticed by the general public, environmentalists, politicians and regulators for the first decade after Mitchell and others revived the technology in the 1990s. This allowed oil and gas entrepreneurs to improve and refine their methods with a minimum of regulatory interference contributing to the impression that it was developed almost overnight.

It is a shining example of what individuals with a vision can accomplish when left to their own devices. It is an example of what still makes the U.S. “innovation central.”

And it is paying huge dividends for all of us in the form of lower electricity bills, lower prices at the pump, and lower prices on everything containing plastics and other oil-based components.

What is easily overlooked is the impact the fracking revolution is having on foreign policy. The increasing global supply of oil and gas has put downward pressure on prices, shifting the balance of power between the Middle East and the rest of the world.

For example, in an attempt to prop up oil prices, Saudi Arabia has cut oil production in recent years. The effort has largely failed due to increasing U.S. production, resulting in skyrocketing Saudi budget deficits. The country’s worsening economy has led to both domestic turmoil, and to Saudi Arabia’s role as the world’s energy power broker being severely curtailed for the benefit of all net oil importing countries. If the economy continues to deteriorate, don’t be surprised if the Saudi’s finally yield to U.S. military and diplomatic pressure and end their sponsorship of Islamic terrorism around the globe.

Without Mitchell and the fracking revolution, it is unlikely that these developments would have taken place or even being imagined. In foreign policy terms this is a prime example of “leading by example at home.” When a country abstains from regulating an industry, adapting a policy of respecting the rights of individuals and corporations (by design or by accident as in the case of the fracking revolution), invention takes off and the country’s strength in the industry in question increases relative to other countries.

If an entire country turns its focus to expanding freedom and protecting individual rights by lowering taxes, cutting government spending, and repealing regulation across industries a couple of things happen: (1) As innovation is unleashed the country’s overall strength increases relative to other countries who are not following the same path, and (2) the countries left in the dust sooner or later start to take notice.

When they do, chances are they will embark on a similar course. Perhaps reluctantly to begin with, but the example set by the leader will not go unnoticed among the citizens of the countries left behind. Over time, the pressure will build on their politicians to follow suit, as watching the leader makes the citizens realize what they’re missing out on. Watch how the calls for reform among Saudi women and young Saudis have been growing stronger as oil prices have been falling — thank you, George P. Mitchell.

A country that adopts as its overarching foreign policy strategy to lead by example at home will also find its defensive military needs easier to support. Expanding freedom and protecting individual rights by lowering taxes, cutting government spending, and repealing regulation will unleash economic growth and over time reduce military spending as a share of the economy. But more importantly, as other countries start copying its policies, they too will become more free and increase the protection of individual rights. As they move in this direction, they will find that they have more in common with the country that led the way, and they will develop into friends and allies, which in turn reduces the potential threats of military aggression.

In 1970, in one of its rare bright moments, the Norwegian Nobel Committee awarded the Nobel Peace Prize to Norman Borlaug, the “Father of the Green Revolution,” in recognition of his contributions to world peace through increasing the food supply.

If the Nobel Peace Prize were awarded posthumously, Mitchell would be a deserving candidate; future historians may look back at the first half of the 21st century and conclude that the “Father of the Fracking Revolution” deserved a place on the same pedestal as Dr. Borlaug, sharing the distinction of having done more to promote world peace than all politician and peace activist Nobel Laureates combined.

The U.S. is singularly equipped to adopt an explicit foreign policy based on leading by example at home. Unleashing the innovative powers of future George P. Mitchells in every industry, allowing their genius, drive and determination to send ripples around the globe, is the only way to achieve that elusive goal strived for by so many — world peace.