Marco Rubio bought a bunch of stuff he probably couldn’t afford. Welcome to America.

So The New York Times has pulled together another hit piece. This one insinuating that Rubio —who the newspaper evidently believes is the GOP frontrunner—is both a reckless spendthrift and financial failure.

The story, either clumsily—or, more likely, deliberately— confuses off-shore fishing boats with “luxury speedboats” and pickup trucks with SUVs to render a distasteful account of Rubio’s financial life. But what we really learned is that, though Rubio is not great with money, the Florida senator has relatively modest desires, considering his fame. The features the kinds of struggles that middle-class voters often face when juggling bills, family, and their investments.

Rubio, the Times tells us, made a series decisions over the past 15 years “that experts called imprudent.” (Can you imagine an expert auditing all the fiscal decisions you’ve ever made?) Rubio stacked up “significant” debts before making serious money and he “splurged” on “extravagant” purchases after securing his $800,000 advance on his book. The man has a “penchant” to spend heavily on “luxury items” like a boat in Florida and he also leased a 2015 Audi Q7.

It didn’t end there. The Rubios went nuts with an “in-ground pool”—instead of a cheaper above-ground model—a “handsome” brick driveway, “meticulously manicured shrubs,” and “oversize windows.” At the same time, Rubio, still one of the poorest senators according to the Center for Responsive Politics, carried a “strikingly low” savings rate, the newspaper points out. And his inattentive accounting methods also lost him more money.

As far as the politics go, The New York Times could not have done Rubio a bigger favor. Convincing voters that you’re one of them typically takes millions, a fabulist tale about your upbringing and maybe a Chipotle stop or two. Convincing them that you have empathy for their situation is an even more formidable task. But Rubio once struggled like all of you. As Christopher Hayes tweeted, “Starting to think Rubio has some plant in the NYT and these supposed ‘hit-jobs’ on him are false flags made to make him look sympathetic.”

The question is: does any of this really matter to voters?

I’m typically uninspired by candidates who pretend to be like me or, even worse, are anything like me. I’m terrible. I wouldn’t trust me with anything too serious, and I probably wouldn’t trust you, either. So when I do vote, my decision is driven by the ideological outlook of a candidate or, as is far more often the case, how much I detest the ideological outlook of the rival candidate. Whether that candidate is a billionaire or spends spare time helping autistic orphans in inner cities or shovels his own snow does not matter. People with compelling ideas and the right temperament for the job can emerge from any facet of society.

But I realize many Americans disagree. They distrust elites. They want candidates who understand them. For Republicans, Rubio has something that neither Mitt Romney nor George Bush could muster: a non-theoretical grasp of how a child of working-class parents can find success in America.

There really is nothing inherently inappropriate about the media scrutinizing the fiscal lives of candidates. If you’re going to run for president, voters are going to be naturally curious about your past conduct and choices—especially in an age when politicians have few qualms about involving themselves in your personal decisions. The problem with the New York Times investigation isn’t so much that it’s a transparent attempt to paint Rubio as an unfit candidate, but that the paper exhibits an ugly double-standard in coverage.

Although he was more fiscally responsible than Barack Obama at the same stage of his life, it should be mentioned that Rubio, like many of us, is less reckless than he seems. Even though he was “struggling with debt,” Rubio probably understood that money was in the pipeline. Whether he wins the presidency or not, there’ll be a flood of opportunities to profit on his fame and connections. Many American lives—though with far more modest figures—are on a comparable trajectory. Most of us have to borrow to pay for our educations, houses, and fancy windows, but we expect those investments will pay off at some point. It’s a risk, of course, that comes with varying levels of success.

Listen, some folks make $100,000 trading cattle futures their first time out of the gate and others have to take on mortgages and wait years for their property to appreciate.

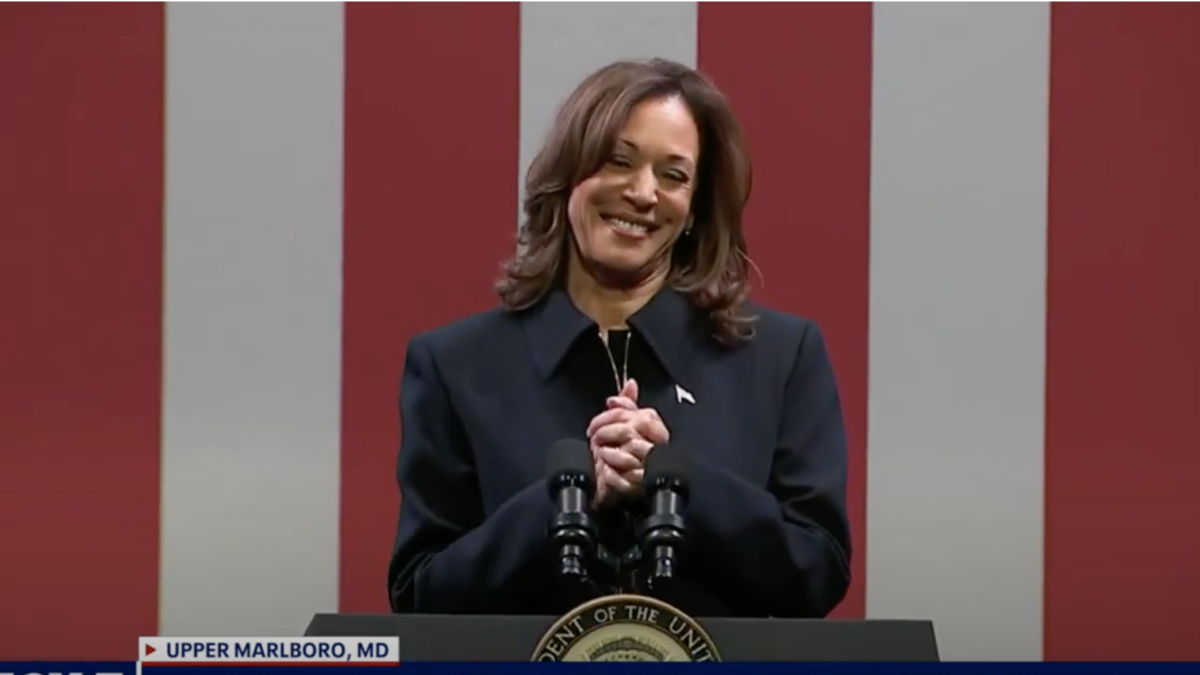

Which reminds me. Watching fans of Hillary Clinton attack Rubio for his fiscal failings should be a comic experience. It isn’t because Hillary is preposterously wealthy for someone who has accomplished so little. It’s that Hillary got her hands on gobs of cash in a truly detestable manner. Not only has she peddled her influence, but that influence was bought with the success of someone else’s name. If 2016 pits Rubio against Clinton, it won’t pit a guy who has trouble balancing a checkbook against a prosperous and talented woman. It’ll be a race that pits a person whose greed and corruption goes back decades against a guy whose dream, according to The New York Times, is a fishing boat and a nice car—the type of items that many average Americans can still covet.