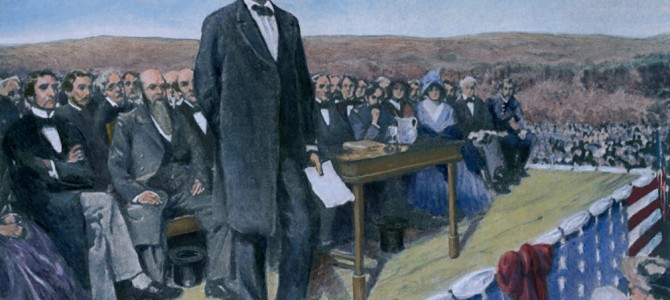

150 years ago on March 4, with General Sherman’s devastating march through Georgia accomplished, and General Grant’s siege of the Southern capitol drawing to a successful close, Abraham Lincoln took the presidential oath of office for a second time. That oath, “to preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States,” had supplied the basis for Lincoln’s broad exercise of executive authority at the outbreak of war four years prior. In the late winter of 1865, that dismal scene had markedly changed.

With a promising military forecast and the Thirteenth Amendment’s passage through both Houses, Lincoln might have used the occasion to boast of his accomplishments. Instead, he sought a lasting testament to the anguish of our Civil War by confronting one of the deepest moral questions to stir man’s soul: Is God just? This question haunts us all at one time or another. For this reason, we too might learn something from Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address, about ourselves and the limits of politics to satisfy our longing for ultimate justice. Lincoln’s argument in the Second Inaugural was not a pragmatic concession to the nation’s immediate needs, but a thoughtful, coherent, principled answer to the question of God’s relation to man, and the sort of action we may be expected to accomplish given that relation.

A Defense of God in a Time of Devastation

Soon after delivering his Second Inaugural Address, Lincoln explained in a private correspondence that he intended his short speech to bring one fact of central importance to our attention: that “the Almighty has His own purposes.” Though we may shrink from this chilling reminder, for Lincoln it is an unavoidable conclusion given four years of brutal civil war.

God is just, to be sure, but the path to the ultimate triumph of His justice meanders painfully through seemingly unnecessary and destructive battles. According to Lincoln, God distributes “woe” for our “offenses,” and this distribution does not appear to follow a strict plan of justice as we wish to have it. For this reason, no one expected for this war a result so “fundamental and astounding,” nor its magnitude and duration. The darkest hours of the Civil War, at Manassas, Antietam, or Gettysburg, and the prospect of evil’s spread were the North ultimately to lose or let go, could only breed despair and anguish.

In the midst of such powerful passions, questions about our place in the whole and our relation to ultimate justice easily come to mind. Without a deeply sewn sense of justice or of faith, the practical result of these questions is a sort of disengaged atheism. Lincoln himself does not succumb to this temptation, but he is aware that the Civil War cannot but raise it for thoughtful citizens. The only way one can avoid that temptation is to recognize the inscrutability of God’s entire purpose. That is, we must accept our ignorance without letting this cripple our desire and drive to act.

Revisiting the Age-Old Question Concerning God and Suffering

Though Lincoln, in many of his public proclamations and private letters, displays all the marks of a pious man, his piety in this case requires him to think through God’s purpose to its very bottom. Lincoln begins this quick investigation with a hypothesis rather than a bold claim, that “American Slavery,” the responsibility for which he assigns to both North and South, might be one of those offences which merit God’s punishment in a bloody war.

Instead of supplying the conclusion immediately, he interposes a question. He asks, looking back on the Civil War, which continues still, “shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which believers in a Living God always ascribe to Him?” Specifically, does this terrible vexation convince us that God’s judgments are neither true nor righteous? Has God forsaken us? Lincoln’s only positive statement at this point is that we are thrown back on our hopes and prayers, longing for the end of this “mighty scourge.” Unhappily, the previous four years of half-answered petitions can inspire no real confidence in a speedy or sure reply.

Lincoln then offers another hypothesis which deepens the pain of the first. Supposing the Civil War is America’s collective punishment, one which God has us inflict on ourselves, to what lengths must we go to fulfill that purpose? Lincoln’s answer is startling. In perhaps the most beautiful passage of this speech, the president claims that the war might “continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword.” On Lincoln’s supposition, God may ask for nothing less than the annihilation of all things built by and for American slavery that count as “wealth.”

How many homes, roads, railroad tracks, telegraph lines, and victuals does this include? On a slave society’s barbaric calculations of moveable goods, how many children could be tallied in this account? Sinking all this wealth calls to mind Sherman’s total war, terrifyingly completed and perfected. Furthermore, the invocation of lex talionis, matching atrocity with atrocity, quickens northern spiritedness into boiling anger. Far from paving the way for an ultimate reconciliation between North and South, these two extreme measures draw and darken the line separating friend from enemy. Could the North reunite with the South if it followed this terrible path marked out by God? Could the South forgive the North this fresh transgression?

Yet from these questions grow others. If fulfilling God’s purpose is to annihilate slavery, would such material devastation secure a “just and lasting peace”? If republican government draws upon and cultivates its own characteristic habits of mind and heart, then lenience precisely where these crucial attributes of the American soul are lacking would not fulfill the purpose we choose to follow. This would in turn dictate harsher peace terms than Lincoln was willing to consider at the time. At this point, Lincoln’s suppositions require more retaliatory justice than mercy, the effect of which is to separate friend and enemy and to diminish Lincoln’s hopes for a reunited America.

A Shift from Vengeance Towards Mercy

These thoughts flood us with despair at a God who asks too much. Lincoln nevertheless demands that we fulfill whatever purpose we suppose to be the Almighty’s. But Lincoln, having brought to our attention the question which the Civil War engenders in us, does not ask us to ignore entirely our all-too-human doubts. He allows us our anguish. We needn’t believe in the depths of our hearts that “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.” We must only repeat it with our lips, with the sincere hope that the heart will soon follow.

A firm belief in the truth and righteousness of God’s purpose is for Lincoln the beginning of justice. Yet, because this belief is rooted in a string of hypothetical “ifs,” all that justice requires of us is seen only in dim outline. This fact, that we do not and cannot have absolute knowledge of justice, restricts what actions we can rightfully take. We can know enough to act, and when we act we must do so with strength. We cannot, however, let that fortitude convince us, as surely it can when inflated beyond reason, that we fully know moral truths. Knowledge of our ignorance directs us away from the potential excess of moral vigor and, in the case of reconstruction, toward mercy and charity.

And so, Lincoln ends with a call to charity, not based on our absolute moral knowledge, but on that sliver of justice which God “gives us to see.” Firmly knowing that slavery is evil, but ignorant of the Almighty’s purpose regarding it, America may strive toward reunification, combining stern resolve and charity.

The Second Inaugural Address is a model for political oratory not simply for the beauty of its prose but for the rigor of its argument. Through this speech Lincoln elevates and refines our understanding of what moral action requires, steels our resolve, and directs that resolve away from vengeance and toward mercy. He teaches us how to govern ourselves in a regime dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal, and to accept limits to what we can know and therefore to what we can rightly do.

It is a speech simultaneously for victory and loss. It pumps our blood and twists our hearts. It emboldens us to act strongly, but also chastens our spiritedness and inspires the fellow feeling that is the root of life in common with others. Above all it illustrates that the human longing for justice, to know what it is and live a life according to its precepts, is ultimately beyond the power of politics to satisfy.

In one month we will celebrate the 150th anniversary of the end of our Civil War, and closely upon it we shall mourn Lincoln’s death. That war, which was thrust upon Lincoln and which, through uncommon fortitude he brought to an end, would take his life. The Second Inaugural, as Lincoln’s deepest, sharpest, and most stirring reflection on that war, is a solemn reminder that speech is only as good as the deeds it commemorates or inspires. It is a reminder, furthermore, that great speech springs from deep reflection, and that when that basis is lacking we long all the more for statesmen of Lincoln’s nature.