The political spinmeisters are already getting positioned for the next round of health care debates. They don’t really much care what happens as long as they can give their team credit for anything that seems to be good and blame the other team for anything that seems to be bad.

So Republicans want to be sure that whatever they do bears no resemblance to Obamacare, and Democrats will pounce on anything that seems similar to Obamacare as a vindication of that noble effort.

If a Republican proposal retains 10 percent of the Affordable Care Act, is that “repeal,” or is that “fix?” What about 20 percent? Should Republicans avoid keeping something that might have merit just to deprive Democrats of a talking point? Should Democrats crow about Republican capitulation if something is retained?

Thus, rational public policy will be sacrificed on the altar of political advantage. What else is new?

The Affordable Care Act is the worst piece of legislation ever passed into law in the United States. It was poorly conceived, poorly written, poorly enacted, and is being poorly implemented. The thing is a mess. However, it does open up some doors that were firmly locked before—things that most free-market economists have been espousing for years without success. We should not run away from those things just because they have President Obama’s name on it.

I am not talking about the things the idiot media think are popular—the slacker mandate, open enrollment, equal premiums for men and women, and free “preventative” services. These are all terrible ideas for reasons I won’t go into here (unless you insist).

I’m talking specifically about several more important elements of the law that were not well crafted in this particular bill, but can now be used as precedents for major improvements in American health care. For example:

1. Breaking the tie between employment and health insurance. It is simply not possible to overstate how important this is. The advantages given exclusively to employer-sponsored coverage have badly warped, not just the health care system, but employment and labor policy, as well. It also spawned the creation of Medicare and Medicaid. These programs were enacted in 1965 in part because the elderly and the poor were the two groups of Americans who could not benefit from the health care advantages government gave workers.

Most people are aware that the only reason we have a job-based insurance system is as an artifact of the wage and price controls of World War II. Companies couldn’t attract workers by offering higher wages, so they offered “fringe” benefits instead. The Internal Revenue Service said such benefits would not be considered taxable income. They were “excluded” from the tax rolls.

This might have worked in the post-war era when families were typically made up of a single-wage earner who worked for the same company most of his (usually a “his”) life, and divorce was uncommon. But it makes no sense at all in today’s society where people change jobs frequently, both spouses work, divorce is common, and child-rearing responsibilities are divided. It is typical today for a husband and wife to each get coverage from his or her own employer and make kids a jump ball depending on which parent has better dependent coverage at any given time.

The State Children’s Health Insurance Program complicates things even more by placing the kiddos in a government program, which means many families have three different insurance plans to contend with: one for the working mother, another for the working father, and yet a third for the children. Understanding one insurance plan is difficult enough.

Conversely, both spouses may be covered on the husband’s policy, but if he becomes eligible for Medicare, the wife is left to get her own coverage in the individual market. Changing jobs usually means a period of non-insurance because even if the new job provides coverage, there may be a waiting period for eligibility. And in all these cases it isn’t worker choosing what is covered, but the boss.

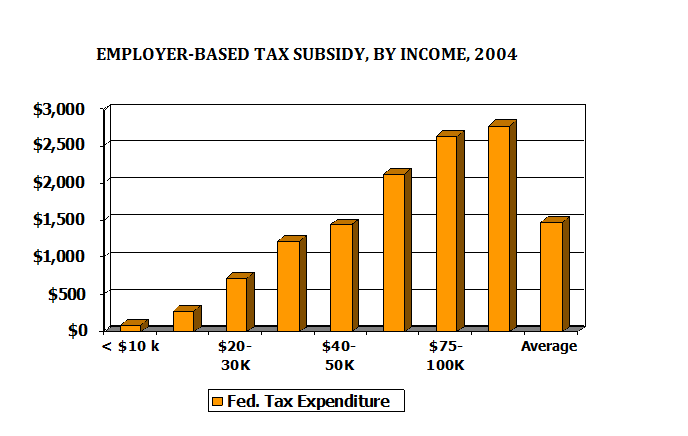

Further, the exclusion is the most regressive tax policy imaginable—the higher your income the greater your tax savings. See the chart below.

The whole concept of getting coverage as a benefit of employment is a disaster, and many of us have been advocating a move to individually-owned insurance for a very long time, without success. Employers resisted such a change because providing coverage locks workers into their jobs, and Democrats have been wary of “throwing people into the vagaries of the non-group insurance market.”

But Obama got it done. Yes, there is a façade of continued employer-based coverage, and there is even a mandate on employers. But that mandate isn’t really a requirement to provide coverage. It is a way of taxing those employers who do not. The tax cost is trivial compared to the cost of providing coverage, and the incentives are strong for employers to pay the tax and drop the coverage. Granted, it will take a few years for the corporate culture to change enough to allow that. But that is as it should be. There always needs to be a transition period when implementing as big a change as this.

2. Tax credits for individually-purchased health insurance. One of the reasons the individual market has had troubles is because there has been no subsidy for it. Anyone who can possibly get employer-sponsored coverage will do so because paying premiums with after-tax dollars nearly doubles the cost of coverage for most people. So the potential market for individual coverage has been very limited, largely confined to people with loose attachment to the workplace—early retirees, people with several part-time jobs, seasonal workers, independent contractors, and so forth. See my explanations here and here.

Conservatives have tried and failed for years to extend tax benefits to individuals who buy their own coverage. But Obama got it done.

Now, the way Obama did it is cumbersome, bureaucratic, and unfair. Many millions are receiving subsidies without being qualified for them because the government has no way to verify their status. Many others will be reluctant to improve their earnings because they will lose their subsidies.

Bob Moffitt and Alyene Senger write about this problem. They commend the proposal Sen. John McCain put forth during the 2008 campaign. It would have provided a flat tax credit of $2,500 per person or $5,000 per family. This would have applied to all insured Americans, including those with employer-sponsored coverage. This would have been administratively simple and, importantly, would not have discouraged work.

Add to this John Goodman’s idea of applying the tax credit to safety net providers for those who do not buy insurance, and you have a universal system that is fair to everyone without having to mandate that people buy it. Is the dollar amount sufficient? Goodman says this is what the Congressional Budget Office estimates the cost of enrolling new people into Medicaid, so, yes, it should be adequate.

These good ideas have been floating around conservative policy circles for a very long time, but only President Obama was able to break the ice and get a tax subsidy enacted for those who own their own health insurance. Now that the precedent has been set, there is no going back. The only question is how to best design the subsidy, something that was not really debated during the enactment of Obamacare.

3. High-deductible health insurance. Obamacare has also broken the ice on the acceptability of higher deductibles. This idea was despised in Progressive circles for decades, but now it is commonplace.

When the concept of Medical Savings Accounts (MSAs) was first introduced in the 1990s, it had broad bipartisan support. John Breaux, Dick Gephardt, and Tom Daschle all favored the idea at first. But, thanks largely to Ted Kennedy, Democrats were soon bullied into opposing it and it became strictly a Republican proposal. The charge was that MSAs and later Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) would be a boon to “the healthy and wealthy” but a disaster for everybody else.

Conservatives argued these charges were false. A typical product design might have a $2,500 deductible with a tax-free cash account to pay for expenses up to the deductible. Very often the savings on premiums would be enough to fund most of the account, so the non-wealthy would have a chance to save a large amount of money that would otherwise be paid to an insurance company. And the non-healthy would be better off because once the deductible was met coverage would be 100 percent of costs, unlike most other programs, which require a 20 percent coinsurance.

Meanwhile, conservatives maintained, high-deductible plans with an HSA would prompt people to pay more attention to their spending, seek out lower cost treatments, and become better informed about their options. This would lead to a healthier population and lower costs over time.

Of course, both sides were simply speculating at first. There was very little experience to support either side of the argument. Which side was more correct would have to be tested in the market under real-world conditions.

As it turns out, conservatives were right and progressives were wrong. In the ten years since HSAs first became law, everything the conservatives predicted has come true. HSAs lower costs and get people more engaged in their own health care decisions. See, for instance, these two write-ups of a RAND study that examined HSAs impact on “vulnerable populations,” here and here.

Enrollment is large and growing. The Employee Benefit Research Institute reports that enrollment grew by 16 percent just between 2012 and 2013, and that 78 percent of large and 64 percent of medium-sized employers will offer them by 2016. EBRI also finds that workers in an HSA or other “consumer driven health plan” (CDHP) are much more likely to engage in “cost-conscious behaviors” and participate in wellness programs.

Still, progressives resisted the idea of an empowered consumer. Just last year some researchers at Harvard University published an article in Health Affairs decrying the “burden” of high deductibles. As I wrote, while these researchers think any direct out-of-pocket payment is wicked, they seem unconcerned about the burden of higher taxes or higher premiums required to avoid such payments.

Now, conservatives have supported raising deductible to $2,500 per person or so and offering HSAs to help offset those expenses. But Obamacare has blown the doors off that level of cost sharing. In the exchanges, deductibles of $6,000 per person and $12,000 per family are commonplace, and there is additional cost-sharing on top of that and no savings account to ease the pain of such high out-of-pocket costs. HSA programs seem downright generous in comparison.

So, here are three conservative ideas that have been fiercely resisted by liberal Democrats in the past, but are now baked in to Obamacare. There will be no going back. Whatever Republicans might do in the future to improve the health care system, these items will be essential.

Who cares if a healthcare proposal is labeled Repeal, Replace, or Fix? If it is done right (that is, not like the current law) it will get us on the road to a much better health care system.