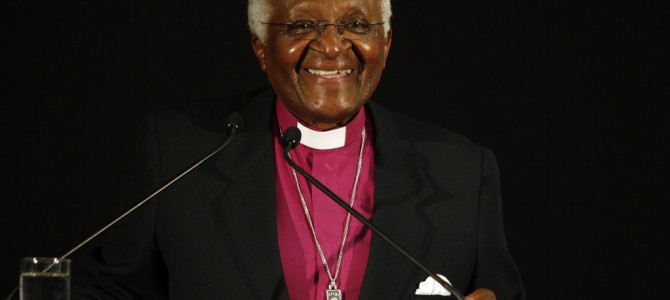

The proposed Keystone XL pipeline between the United States and Canada is one of the most prominent battles in the larger war between environmentalists and economically-informed political advocacy today. Earlier this month, retired Anglican archbishop Desmond Tutu of South Africa took to the pages of The Guardian to inveigh against the pipeline’s latest phase, which would provide a new connection between the oil sands of Alberta in Canada and refineries in the United States.

For Tutu, such movement of oil between nations is akin to an environmental and moral catastrophe. He argues that the pipeline “could increase Canada’s carbon emissions by over 30%” and that the consequences would be devastating. Keystone “will affect the whole world, our shared world, the only world we have. We don’t have much time.” The urgency of the situation is due to the perceived threat of climate change, and Tutu’s proposed response is a massive boycott, including a “fossil fuel divestment campaign,” akin to the tactics used in the “anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa.”

Tutu’s rationale arises from a particular reading of the Christian responsibility to care for the environment, one which meshes well with the near-religious zealotry of anti-development environmental activists. As Tutu puts it, human stewardship of the natural world involves “a responsibility that begins with God commanding the first human inhabitants of the garden of Eden ‘to till it and keep it’. To keep it; not to abuse it, not to destroy it.” This is true enough as far as it goes; human beings are called to responsible stewardship. But Tutu’s depiction aligns with a view of the environment as a pristine wilderness which must be preserved rather than cultivated and developed, and is in this way the antithesis of responsible stewardship.

The preservationist account of Christian environmental responsibility tends to view human activity as destructive and abusive in ways that parallel the secular and even pagan perspectives of other environmental activists. This is also why such accounts, whether Christian or not, tend to view the human population as a problem to be controlled rather than a blessing to be celebrated. Robert Nelson has persuasively argued that environmentalism has become one of two major modern secular “religions” competing for authority in the public square. The other is a kind of “economic” religion, which uses only the logic of material growth to judge the merits of policy. As Nelson puts it, these are two sides of a basically progressive ideology. Where economism preaches salvation by ever-increasing exploitation of the material world, environmentalism proclaims a green gospel: “In environmental religion, global warming is a sin against God, not an issue to be resolved by economic calculations of possible future benefits and costs to human beings,” writes Nelson.

A hallmark of an ideological and idealistic perspective is a congenital lack of flexibility and ability to compromise. For Tutu and other anti-petroleum activists, there simply is no middle ground on fossil fuels, precisely because this is a great moral and religious conflict. The depiction of the difference between fossil fuels and alternative, “sustainable” sources of energy is stark and incontrovertible, and fossil fuels have become a great shibboleth in this holy war. Tutu’s anti-Keystone activism is an all-or-nothing gambit: “People of conscience need to break their ties with corporations financing the injustice of climate change.” The market, meanwhile, has adapted and found alternative ways of transporting petroleum, and in so doing rendered an environmentalist victory on Keystone symbolic at best.

A more biblical and responsible account of Christian stewardship of and care for creation recognizes the complexity of the environmental, economic, social, and political realities at play. Not all fuels are created equal, but there is a continuum rather than a dichotomy between more or less clean, sustainable, and affordable sources of energy. This is a continuum that must include considerations of nuclear power as well as “our own solar panels” and energy-efficient water heaters, as Tutu suggests. In addition, there are sound geopolitical reasons for nations like the United States to seek reliable streams of energy domestically as well as in partnership close neighbors.

A view that sees the Christian stewardship responsibility as involving the mandate to cultivate and be productive is able to do justice both to environmental and economic realities. Oil and other fossil fuels, no less than other aspects of the created order, should be viewed as resources to be responsibly developed and productively cultivated. The best kind of stewardship is economically-informed and environmentally-responsible, norms which are not, in the last analysis, mutually exclusive.

In emphasizing a view of the natural order as something merely to be protected and maintained, Tutu has embraced a dangerous half-truth. The natural world is not, on the Christian view, simply a wilderness to be preserved but is instead both a garden to be cultivated and a city to be constructed. We see the reconciliation of these two realities in the biblical image of the new Jerusalem, a city paved with streets of gold and with a river flowing “down the middle of the great street of the city.” On either side of this river stands the “tree of life, bearing twelve crops of fruit, yielding its fruit every month” (Rev. 22:2). This is a vision of the garden within the city, the consummation of Eden, and the true stewardship of creation demanded by the Creator.

Dr. Jordan J. Ballor is a research fellow at the Acton Institute for the Study of Religion & Liberty, and author most recently of Get Your Hands Dirty: Essays on Christian Social Thought (and Action). You can follow him on Twitter @JordanBallor.