You may recall a notorious moment from one of the 2012 president debates when President Obama cited Mitt Romney’s warning about the growing threat from Russia and dismissed it with a snarky one-liner: “The 1980s are now calling to ask for their foreign policy back.”

Fast forward a year or so, and President Obama faces the biggest foreign policy crisis of his presidency: Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, which brings the curses of war and imperial conquest back to Europe.

Let’s dispense, by the way, with the journalistic evasion of calling this an “invasion of Crimea,” as if the Crimean Peninsula were not part of the sovereign territory of Ukraine. While Putin may be particularly interested in securing the Russian naval base at Sevastopol, he knows very well that he can’t hold Crimea on its own, since it is dependent on the mainland for power and water. No, it’s clear that Putin is interested in carving off a large Russian-speaking slice of Eastern Ukraine. It’s just as clear he would like to take all of Ukraine, which is why he and his mouthpieces have been busy delegitimizing the new Ukrainian government and denouncing the victorious opposition in Kiev as “fascists,” which is most definitely a fighting word.

Putin is reviving the Brezhnev Doctrine, in which the Soviet Union declared that it could invade any country that tried to escape its domination. The Brezhnev Doctrine was summed up as “once you go Communist, you never go back.” Putin’s version is a bit cruder. The Putin Doctrine is: once you become a kleptocratic dictatorship subservient to Moscow, you never go back.

So what do we do? How can we roll back Soviet—er, Russian—aggression?

The 1980s are calling. They want to know if we want their foreign policy back.

Why should we look to the 1980s? Because that was the decade when we broke the Brezhnev Doctrine. By the end of the 80s, as Eastern European countries began to throw off the Communist yoke, the Brezhnev Doctrine yielded to the Sinatra Doctrine: Russia would let the countries of Eastern Europe do it their way.

What lessons can we learn for a new age of Russian imperialism?

First, when the aggression comes, it’s too late. President Reagan was mortified, when the Soviets demanded a crackdown on the Solidarity movement in 1981, that there was so little America could do about it, given the decline of our military power in the backlash against the Vietnam War. Barack Obama finds himself in in the same situation, given the decline of American military power that he has presided over in the backlash against the Iraq War.

But Reagan found plenty to do in Poland without using our military power. We imposed sanctions against the Polish regime and the Soviet Union, and throughout the 80s we gave Solidarity everything from moral support, to money, equipment, and training.

We did the same thing on a bigger scale in Afghanistan, providing extensive covert military assistance to the Afghan insurgency, including intelligence, training, and huge quantities of weapons. This famously included Stinger portable anti-aircraft missiles, which so terrified Soviet pilots that ground troops began to refer to them as “cosmonauts” because they would stay at high altitude and refused to offer close air support.

Afghanistan was the last place the Soviets implemented the Brezhnev Doctrine, and they soon regretted it. But Afghanistan was never just about Afghanistan. It was about breaking the world’s fear of the Red Army. The message was: if we can do this to you in Afghanistan, imagine what we can do to you in Poland.

Or central America, where American weapons and training helped beat back Communist insurgents in El Salvador, and just the suggestion of US support summoned into existence a resistance army to oppose the Sandinista regime in Nicaragua. We made similar efforts to roll back Communist expansion in Cambodia and Angola.

Please note, as a lesson to anti-interventionists on both the left and the right, that all of these actions were indirect and comparatively small in scale. This is the real truth of “peace through strength”: the stronger and more vigorous our policy, the less we actually have to do.

In fact, the biggest direct military intervention of the Reagan era was a US invasion of the tiny island of Grenada. This action was small but important, putting a quick end to Cuba’s attempt to militarize the Caribbean.

All of these specific interventions were backed by a wider policy: a renewed commitment to support our NATO allies and a massive military buildup backed by an economic revival. This was the material backing for renewed ideological opposition to the Soviets, including repeated public recognition of the evil of Soviet domination, from the “evil empire” to “tear down this wall.”

All of this was summed up in the Reagan Doctrine: a commitment to counter the Soviets and roll back their influence worldwide, point for point. This came from the president whose strategy for the Cold War was: “We win, they lose.”

If President Reagan could see what Russia is doing today, he would cock his head and say, “Well, there they go again.” And then he would deploy the whole panoply of resistance we used against Moscow in his day. He might start with the fact that Poland has strong ties to Ukraine’s pro-European majority and a direct interest in opposing Russia, making the Poles an obvious conduit for support to the new government in Kiev—both open and covert, and both economic and military. The Baltic states are also freaking out, given their own vulnerability to Russian aggression, and they can be counted on for extensive support. The urgent priority is to rapidly convert Western Ukraine into a “porcupine state”—one that may not be able to win a war with Russia outright, but can make such a war too painful to be appealing.

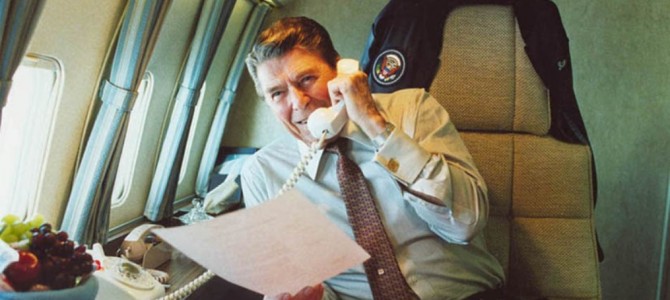

Instead, we get President Obama’s totally ineffectual response, in which he spends 90 minutes on the phone to warn Vladimir Putin that invading Ukraine would “negatively impact Russia’s standing in the international community.” As Julia Ioffe replies: “as if there’s much left or as if Putin really cares.”

Implementing the lessons of the 1980s will require a lot of money and a lot of effort, and some tough decisions that will be very unpopular in the halls of the United Nations. It will also require something this president has found even more difficult to do: challenging the preconceived notions of the left.

But we know what it looks like when American weakness and uncertainty allow an aggressive dictatorship and its allies to advance across the world. To avoid that outcome, we need to reverse course and do it fast.

If we don’t, pretty soon the 1970s will be calling.

Follow Robert on Twitter.