What does totalitarianism look like? Ask leftist corporate media in this last month of the presidential election, and you’ll get one answer. “New fears that Trump threatens democracy,” reports CNN. “Trump Is a Threat to Democracy,” declares New York Magazine. Rolling Stone offers “A Guide to Trump’s Fascist Rhetoric.”

There is a certain absurdity to this alarmism, given that former President Donald Trump was already a democratically elected president, vacated the White House, and is once again competing in an election in which his ticket will be beholden to a bureaucratic process guided by thousands upon thousands of election officials. That certainly doesn’t sound like authoritarian behavior.

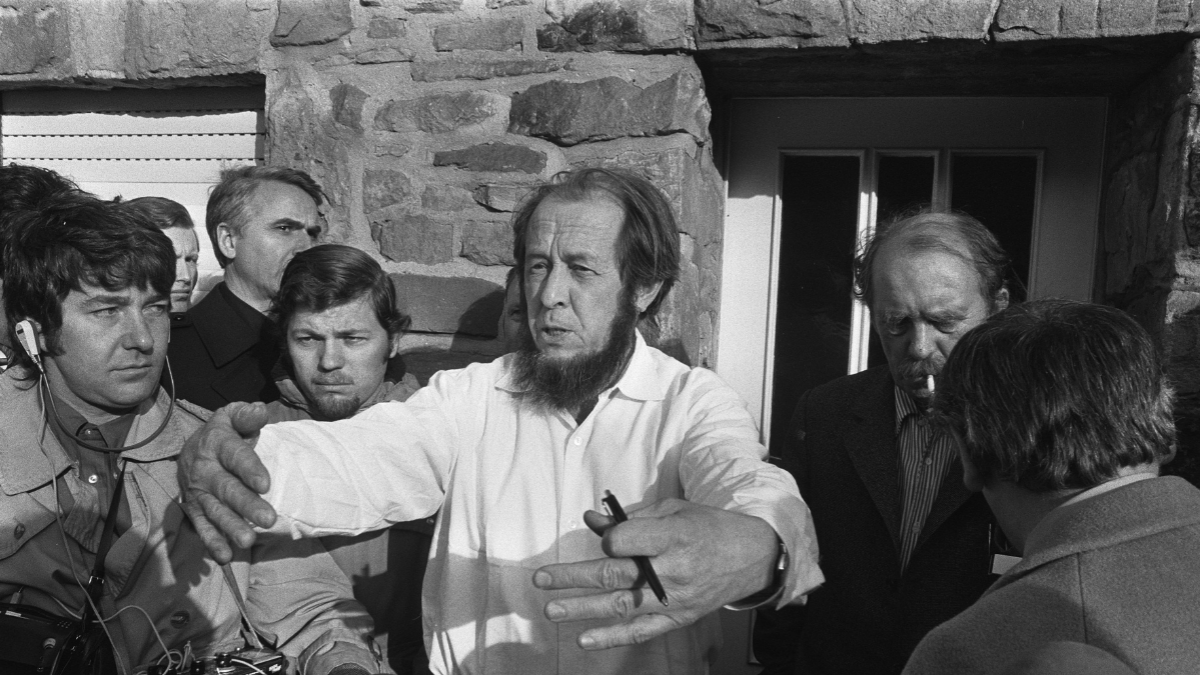

Perhaps it would be worthwhile to revisit the tenor and texture of actual authoritarianism. The 50th anniversary of Russian author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago circulating throughout the former Soviet Union offers an extensive, disturbing lesson on how coercive, unaccountable governments can vitiate human freedom and flourishing.

The ‘Best Nonfiction Book of the Twentieth Century’

It is difficult to overstate the importance of The Gulag Archipelago, written by one of the most important writers of the 20th century. Solzhenitsyn, once an ardent communist and atheist, who was twice decorated while commanding an artillery battery during World War II, became increasingly disenchanted with Stalin and the brutality of the Red Army during his service in East Prussia. Private letters criticizing the Soviet regime were uncovered, and Solzhenitsyn was convicted of “founding a hostile organization” and sentenced to an eight-year term in a labor camp. Through this harrowing experience, Solzhenitsyn underwent a profound religious and political conversion.

After his release in 1953, Solzhenitsyn began writing about his experiences suffering under the callous brutality of Soviet totalitarianism, and ultimately his writing reached its apotheosis in the three-volume Gulag Archipelago. The paperback edition of the first volume alone sold more than 2 million copies, and the book effectively silenced Western intellectuals who for decades had expressed glowing admiration for Soviet communism. A review in Time magazine labeled the book no less than the “best nonfiction book of the twentieth century.”

What Solzhenitsyn Saw

Entire doctoral dissertations have been written analyzing Solzhenitsyn’s magnum opus, but for our purposes here, it is enough to observe some of its most salient themes. The first of these would be the ubiquity of party purity tests, the means by which communists were expected to demonstrate their unwavering commitment to the regime. Any derivation from the party line, no matter how absurdly insignificant, could be viewed as insubordination and risk not only one’s career but even one’s life.

In one amusing scene, Solzhenitsyn describes a hall full of party members, all applauding, everyone afraid to be the first to stop clapping for fear of being labeled a dissident. “They couldn’t stop now till they collapsed with heart attacks!”

What awaited those dissenters, whether they be real or imagined, was a byzantine bureaucratic process that degraded and dehumanized its victims to break their will to fight. The outcome of cases brought against alleged offenders was always predetermined in order to eliminate all perceived threats and send a message to potential subversives. It had its desired effect: “For several decades political arrests were distinguished in our country precisely by the fact that people were arrested who were guilty of nothing and were therefore unprepared to put up any resistance whatsoever. There was a general feeling of being destined for destruction …”

The agents of this autarchic Soviet apparatus were unaccountable, self-aggrandizing bureaucrats of middling intellectual abilities. Their power was practically uncontestable, their decisions “always right.”

Their preferred targets were often dispassionate professionals focused on faithfully performing their jobs and uninterested in revolution — for such persons will inevitably prioritize common sense and science over ideology and its narrowing delusions. “If they hurried, they were hurrying for the purpose of wrecking,” writes Solzhenitsyn of the charges brought against meritocrats. “If they moved methodically, it meant wrecking by slowing down tempos. If they were painstaking in developing some branch of industry, it was intentional delay, sabotage.”

The result, of course, was a type of societal suicide, persecuting the most competent because of their unwillingness to conform to the mindless, capricious dogmas of the elite class.

What Do You See?

It doesn’t take a Ph.D. in Russian literature to perceive the overlap between Solzhenitsyn’s Soviet dystopia and America today. Party purity tests are administered by H.R. departments promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion. Failure to engage in the correct performative gestures honoring woke creeds regarding race or sexuality often has serious professional and social consequences, as many even on the left have learned.

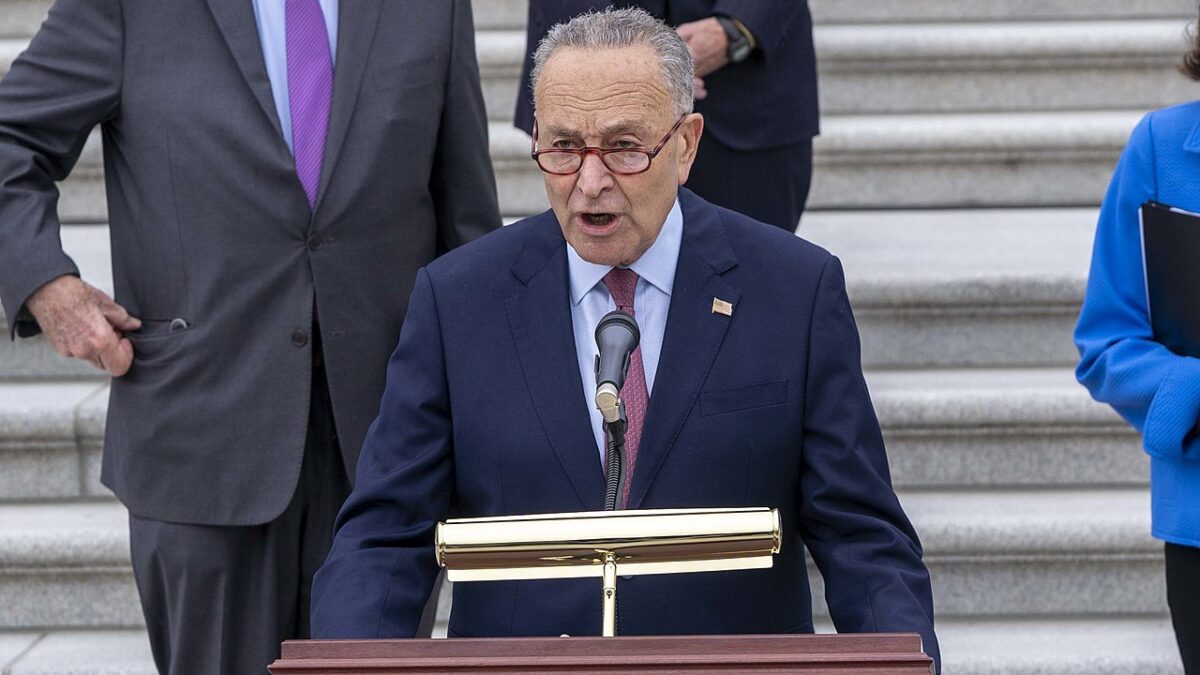

Federal agencies in turn leverage their powers against the Democrat Party’s political opponents, from the Internal Revenue Service’s patently biased scrutiny of conservative groups to the Department of Homeland Security claiming that white nationalists present the greatest domestic security threat to the Department of Justice targeting pro-life groups. The same happens at the state level: New York Attorney General Letitia James has notoriously conducted lawfare against the National Rifle Association and Trump.

Today the total federal workforce is composed of approximately 4.3 million employees (including military service members, who comprise almost half of that number). Federal employees vote Democrat by a not insignificant margin. This is unsurprising, given that the right for decades has been calling for a reduction in the size and influence of the administrative state — which now exercises executive, legislative, and judicial powers, as Ned Ryun argues in his new book, American Leviathan: The Birth of the Administrative State and Progressive Authoritarianism.

Solzhenitsyn himself recognized the potency of this threat, quoting one senior Soviet leader who declared: “It is very good that the legislative and executive power are not divided by a thick wall as they are in the West. All problems can be decided quickly.”

The victims of the managerial class and its stultifying ideology, in turn, are meritocrats, independent and creative thinkers, and ultimately our nation itself. Affirmative action in business and government undermines excellence across our institutions, ensuring that racial and gender quotas take priority over innovation and success. In the military, as Will Thibeau has recently argued, the de-emphasis on merit in favor of DEI initiatives has severely compromised its readiness for the next conflict.

‘Tiny Droplet[s] of Truth’

In The Gulag Archipelago, Solzhenitsyn speaks of “tiny droplet[s] of truth,” those various moments — in which there are revelations of the blatant hypocrisy of our managerial class or the exposure of the lies of the propaganda machine — when citizens even in an oppressive environment can perceive the world for what it is. We have our fair share of recent examples, whether it be the confused, capricious nature of pandemic restrictions; the dramatic rise in crime following the left’s embrace of the “defund the police” movement; trans activists impressing their sexual beliefs on prepubescent children; or unprecedented numbers of illegal immigrants overwhelming local municipalities.

It is these tiny droplets of truth that must remind us of what totalitarianism really looks like, and what our future will be if we fail to resist its many manifestations. The effects of that deadly ideology ruined a once proud people. Perhaps it could have the same effect in our own once glorious republic. But it seems doubtful the agent of that change would be Trump.