A complaint I hear increasingly leveled at contemporary American politicians is that they are out of touch with voters, if not downright contemptuous of them. On a number of core issues, politicians seem less concerned with pursuing policies that are deeply unpopular with ordinary Americans than with upholding the ideologies and self-interests of the ruling elite. Two dramatic examples of this political disconnect with average citizens are the refusal of urban governments to prosecute violent criminals, which has caused a surge in crime, and the White House’s tolerance of mass immigration, which threatens jobs, security, and the rule of law.

As I survey the current political and intellectual landscape, I cannot help but see a resurgence of the arrogance and disdain of the 18th-century French revolutionaries for those they considered to be incapable of rational thought and moral behavior. But I am moving too fast. Let me slow down and give some historical background.

In The Roads to Modernity: The British, French, and American Enlightenments (2004), Gertrude Himmelfarb distinguishes, convincingly, between the French philosophes, who championed reason; the American Founding Fathers, who concentrated on liberty; and the British moral philosophers, who emphasized human nature, benevolence, and our shared, internal moral sense.

While the English reformers showed compassion for the poor and uneducated and treated them as members of the same human race, and the American framers sought to ensure freedom for all classes, most of the French intellectuals looked down on the peasants, dismissing them as bestial and irrational, filled to the brim with the prejudices and superstitions of the Catholic Church. To the philosophes, the common people were neither honorable nor moral, but ignorant and unteachable, enthralled by religion and profoundly non-progressive. They were not citizens but the rabble. Even Rousseau, who extended some sympathy to the masses of the countryside, felt they needed to be guided by those who were enlightened to adopt the “general will.”

“In his article on the Encyclopédie,” Himmelfarb writes, “Diderot made it clear that the common people had no part in the ‘philosophical age’ celebrated in this enterprise. ‘The general mass of men are not so made that they can either promote or understand this forward march of the human spirit.’ In another article, ‘Multitude,’ he was more dismissive, indeed contemptuous, of the masses. ‘Distrust the judgment of the multitude in matters of reasoning and philosophy; its voice is that of wickedness, stupidity, inhumanity, unreason, and prejudice. … The multitude is ignorant and stupefied. … Distrust it in matters of morality; it is not capable of strong and generous actions … heroism is practically folly in its eyes.’”

Diderot, like Rousseau, believed that the masses had to surrender their individual wills to the general will, which would define for them how far they “ought to be a man, a citizen, a subject, a father, a child, and when it is suitable to live or to die. It is for the general will to determine the limits of all duties.” For Diderot and the philosophes, though not Rousseau, what set them above the masses was their superior grasp of reason.

“The moral sense and common sense,” Himmelfarb explains, “that the British attributed to all individuals gave to all people, including the common people, a common humanity and a common fund of moral and social obligations. The French idea of reason was not available to the common people and had no such moral or social component.”

As a citizen in a representative democracy, I expect our political leaders, including Donald Trump, to be held up to public scrutiny and questioned, even investigated, when the facts warrant it. What I do not expect, and find increasingly troubling, is the widespread and ongoing demonization and character assassination of all those who support Trump and approve of his candidacy and his policies.

I am old enough to remember how roughly the political establishment treated supporters of Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush, especially if they identified with a conservative branch of Christianity. Reagan and Bush supporters routinely had their concerns ridiculed, motives suspected, and intelligence doubted. Still, the dismissal of Reaganites and Bushies as boobs and rednecks pales in comparison to the viciously sanctimonious profiling of Trump supporters as authoritarian, narcissistic white supremacists utterly unconcerned for the common good.

Whereas the liberal progressives of the 1980s expressed some compassion for the needs and struggles of the working man, the woke philosophes of today express only contempt for those who work with their hands. While carrying on the oppressor/oppressed identity politics of Karl Marx and his heirs, they have reduced America’s blue-collar proletariat to a racist, sexist, transphobic rabble who must be suppressed, managed, and reeducated.

Convinced, as philosophes were, of the “wickedness, stupidity, inhumanity, unreason, and prejudice” of the rabble, today’s progressive philosophical, political, and social engineers have appointed themselves the task of redefining for the masses what Diderot believed the general will should define for them: what it means “to be a man, a citizen, a subject, a father, a child, and when it is suitable to live or to die.”

The ironic difference between the philosophes of the past and the progressives of the present is that the latter have jettisoned reason altogether in their anti-scientific embrace of transgenderism and other uprootings of natural law. The superiority they claim over the masses is not, like that of Diderot, based on their more refined power of reason. On the contrary, their claims of superiority rest on the dubious ground of rejecting truth, logic, and reason as the product of white, patriarchal, heterosexual, and cisgender minds.

No wonder the majority of working men and women in America look to Trump as their advocate. He not only defends their traditional family values, common sense, and God-given humanity. His seems to be the only voice in Washington speaking up for, or even understanding, the joys and woes, hopes and fears, victories and struggles of that “rabble” that the political establishment, on both the left and right, seems only to dismiss, disparage, and despise.

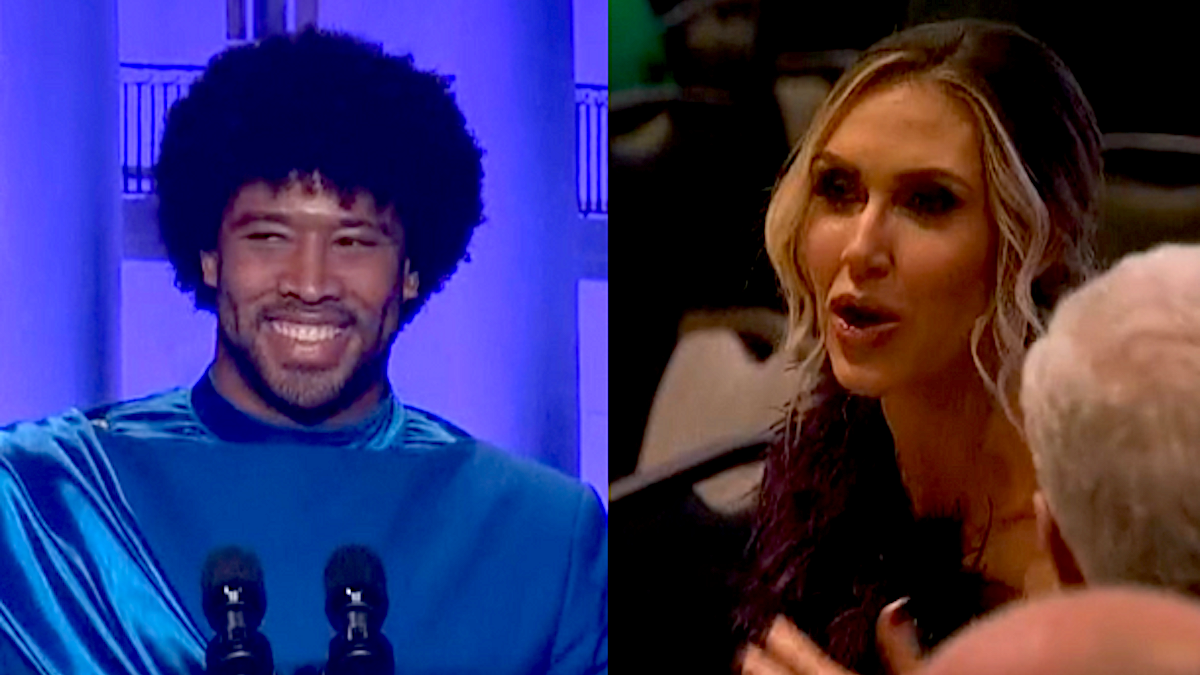

Most of “polite” society attacks Trump for his caustic tone, his cutting remarks, and the obvious glee he takes in labeling and mocking his opponents. They fail to understand that Trump’s rhetoric is central to his appeal. The “masses” who flock to his speeches do not go merely to be entertained. They go to witness a much-needed turning of the tables, a political topsy turvy during which the weapons of the progressive philosophes are turned against them.

Far from the bully, Trump is the champion of those who have been bullied relentlessly and mercilessly by a self-appointed elite who holds them in contempt. In Trump, they have found a modern George Bailey — albeit a crasser and more combative one — who is willing to stand up to the Mr. Potters of the world.

In “It’s a Wonderful Life,” Frank Capra, who combined in his work the American fight for liberty and the British embrace of benevolence and our shared human moral nature, raises up an unwilling hero to protect the working families of his town from a man who would manipulate and crush them to fit his vision of, and general will for, Bedford Falls.

At one point in the film, Potter almost tempts George to come to his side and forget about the lower-middle-class homeowners he has devoted his life to defending. Then George, in a burst of insight, sees through the cold heart and colder contempt of Potter. Rejecting the offer that would have given him the rich and adventurous life he has always dreamed of, he exclaims boldly:

Just remember this, Mr. Potter, that this rabble you’re talking about, they do most of the working and paying and living and dying in this community. Well, is it too much to have them work and pay and live and die in a couple of decent rooms and a bath? Anyway, my father didn’t think so. People were human beings to him, but to you, a warped, frustrated old man, they’re cattle. Well, in my book, he died a much richer man than you’ll ever be.

When the majority of Trump supporters listen to him speak, this is what they hear: a spirited defense of the hard-working despised and a fearless denouncing of the fashionable despisers.