In 2005, Annie George bought land near tiny Tyrone adjoining the Gila National Forest in southwestern New Mexico. To secure her horse, she fenced her acreage with a gate on the road that crossed her property and accessed the national forest.

In response, her neighbor, the U.S. Forest Service, demanded the public have “unfettered” access, tore down the fence, and loosed her horse. She rebuilt the fence, but the agency again removed it, which then occurred a third time.

Matters soon became acrimonious in oral and written communications between George and agency employees. She posted no trespassing signs; the agency sent investigators, took photographs, and collected “evidence.” In 2009, she sued the federal government, its departments, agencies, and bureaucrats.

That she could sue the United States was a right of recent vintage.

The federal government owns a third of the country, and its borders with private landowners run well more than the distance to the moon. Yet for nearly 200 years, citizens and their attorneys had to invent novel legal theories to reclaim land from the United States, without whose permission no lawsuits are allowed. None worked, so Congress, with sole constitutional authority over federal lands, remedied the injustice with the Quiet Title Act (QTA) in 1972.

Congress provided that the QTA was triggered when property owners “knew or should have known of the claim of the United States” to an adverse interest in their property, after which they had 12 years to sue to quiet title.

Congress viewed the deadline as a waivable affirmative defense that the United States could assert. Over time, however, federal lawyers claimed it was more than that.

They asserted, and many federal courts agreed, that a landowner’s failure to file within that period robbed federal courts of jurisdiction to hear the case.

Moreover, federal lawyers broadly defined when property owners “should have known” to include: 1) claims of any interest, no matter how minor; 2) claims without evidence reasonably ascertainable by the landowner; and 3) claims denied by federal employees.

Thus, when George arrived at the New Mexico federal district court, government lawyers argued that, despite the absence of any evidence of federal ownership in the deed she received, she “should have known” of the government’s claim.

When the Forest Service, 26 years earlier, sold the land to one of her predecessors, it reserved an easement, Forest Development Road 6819. The extent of that easement, the agency argued, though undefined in the deed, was found in a 1977 Federal Register notice that barred fencing a “[f]orest development road.”

In response, the district court ruled George’s time to file a lawsuit had passed. In 2012, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit in Denver, Colorado, heard her case.

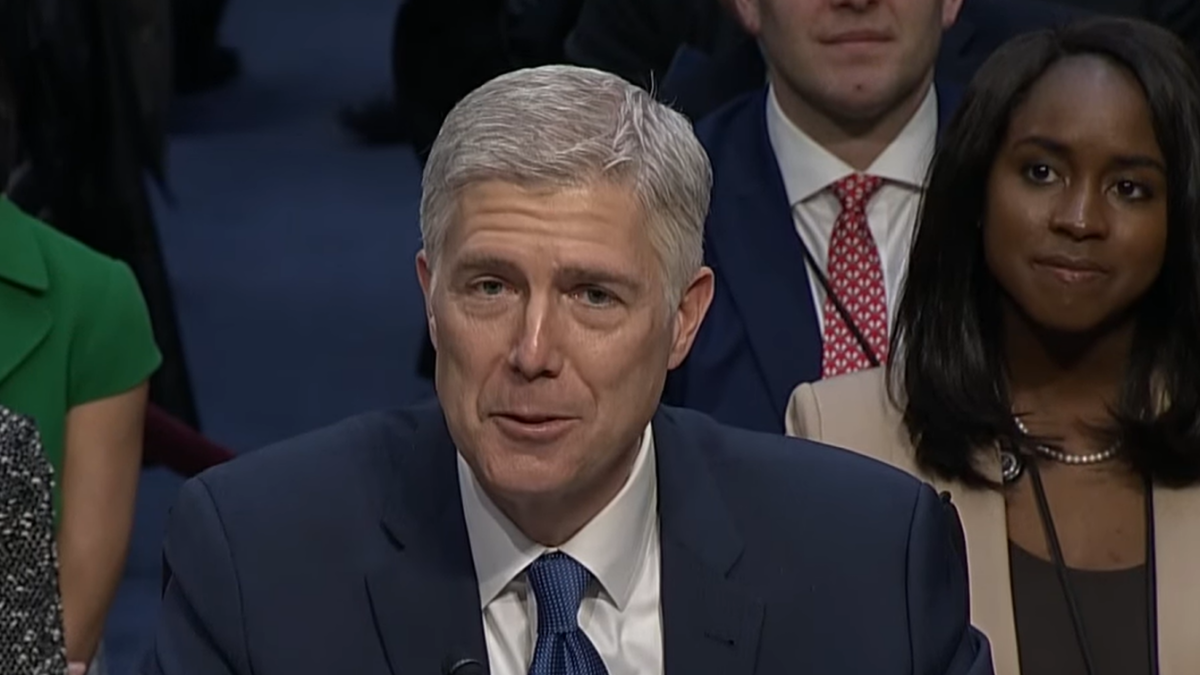

On behalf of the panel, then-Judge Gorsuch, in his fifth year on the federal court that hears appeals from six states, including New Mexico, held that George’s case came “18 years too late.”

He refused to rule on its merits, including whether federal regulations not included in the 1979 deed or the government’s easement could determine the scope of an easement granted by private contract and thus subject to New Mexico property and contract law.

“[W]hether the Forest Service regulations are valid we don’t (and don’t need to) say,” he wrote. “It’s enough Ms. George’s predecessors were legally charged with knowing of them.”

“The problem,” Gorsuch wrote, “is that what the QTA gives [in the right to sue the government] it often proceeds to take away.”

That citizens, therefore, “must turn square corners when they deal with the Government” is not “callous” but merely articulates the obligation that courts adhere to the conditions by which Congress “waive[s] sovereign immunity and allow[s] individuals to tap the public fisc.”

I thought Gorsuch’s ruling “callous,” but I was biased. My outfit represented George and other similarly situated landowners who sought not “to tap the public fisc,” but only to retrieve property rights wrongfully seized by the federal government. That a Federal Register notice doomed her and, decades earlier, her predecessors, was galling.

I recalled Justice Robert Jackson’s dissent declaring it, “an absurdity to hold that every farmer … knows what the Federal Register contains, or [should] peruse this voluminous and dull publication … to make sure whether anything has been promulgated that affects his rights, [assuming] that a reading of technically worded regulations would enlighten him much, in any event.”

Hence, when I learned my friend Jeffrey W. McCoy of Pacific Legal Foundation was at the Supreme Court of the United States on behalf of two Montana landowners who suffered the same fate under the QTA at the Ninth Circuit as we had at the 10th Circuit, I wondered about Gorsuch.

Days ago, in Wilkins v. United States, Larry Steven Wilkins and Jane Stanton, who experienced the sort of mischief that George did, won when the Supreme Court ruled that breaching the 12-year time limit did not stop federal courts from hearing landowners’ cases. The reason was simple: Congress did not clearly say so and neither had the court in its past rulings.

It was great news for the landowners and others like them across the country who have the federal government as a neighbor, as well as for McCoy and Pacific Legal Foundation.

What made the ruling particularly fascinating was the unlikely crossing of philosophical lines. The three liberal justices, with Justice Sotomayor writing for the majority, joined with Justices Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett, over Justice Thomas’ dissent for himself, Chief Justice Roberts, and Justice Alito.

As for Justice Gorsuch’s apparent but most welcomed change of heart 11 years after George’s case, perhaps he explained the reason during oral argument when he declared, while questioning the solicitor general, “There’s a degree of judicial humility required about our own past work.”

How refreshing that a Supreme Court justice appointed by a Republican grows in his position in the right direction.