At the end of January, popular Twitch live-streamer Brandon Ewing — better known as Atrioc — was exposed in a now-deleted post online for allegedly patronizing a pornographic website that specialized in the production of “deepfakes” of online personalities, many of whom were his colleagues on Twitch and his personal friends.

Atrioc was accused of consuming pornography of his colleagues and friends that was generated through artificial intelligence (AI) technology without these individuals’ consent. In an apology stream, Atrioc admitted to the accusations and said he found the source of the deepfakes through advertisements on another porn website. He also admitted he was paying for videos in which AI was used to superimpose the likenesses of his friends and colleagues onto the bodies of pornographic actresses.

The resounding uproar online, originating with a video of Atrioc’s apology that has amassed millions of views, does appear to be justified. After all, he willfully solicited and consumed pornographic content in which the essence of his personal friends and his business partners was stolen and exploited.

The recent development of using AI technology to create pornography of individuals without their awareness or consent is an incredibly pernicious phenomenon. Some online refer to it as a form of “free speech” and suggest its existence isn’t doing harm since the people pictured in the videos are often public figures who are only having their likenesses nonconsensually grafted onto sexual content and are not forced to actually participate in nonconsensual activity.

In some ways, the advent of deepfake pornography is akin to “revenge porn.” But revenge porn, the nonconsensual leaking of sexual materials in order to humiliate and exact revenge upon someone while using prior consent and intimacy as the genesis of this content, largely involves humans exploiting their past interactions with other humans.

Deepfake pornography, on the other hand, is created entirely out of whole cloth through advanced pattern recognition software that is able to fabricate compromising situations in which these people were never participants. Obviously, revenge porn isn’t a morally superior alternative to this, but the fact that these materials can be created through self-automating software ought to be deeply concerning.

There is also little legal recourse for people who have had their likeness used in this manner. Karen Hao of the MIT Technology Review wrote that “46 states have some ban on revenge porn, but only Virginia’s and California’s include faked and deepfaked media.” She continued:

This leaves only a smattering of existing civil and criminal laws that may apply in very specific situations. If a victim’s face is pulled from a copyrighted photo, it’s possible to use IP law. And if the victim can prove the perpetrator’s intent to harm, it’s possible to use harassment law. But gathering such evidence is often impossible … leaving no legal remedies for the vast majority of cases.

Sure, deepfake pornography is akin to revenge porn in that both relate to the dissemination of lewd and compromising materials without an individual’s consent, but deepfakes have the potential to cause more harm than personal humiliation and reputational damage.

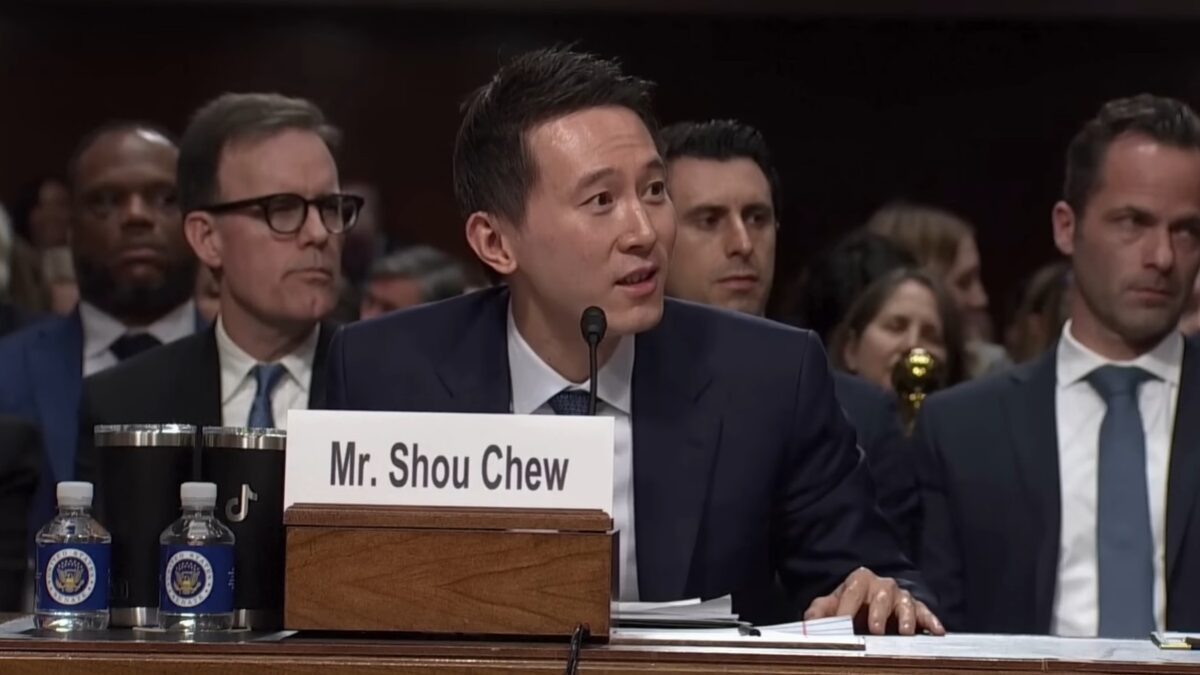

Why couldn’t this same technology be used to falsify evidence or create political propaganda? If it can create high-definition pornography of online personalities, why couldn’t it be used to falsely implicate the leader of a nation in possessing weapons of mass destruction? Why couldn’t well-connected criminals use it to scrub incriminating video of their presence entirely and implicate someone else?

AI technology is very new, but it is developing rapidly and is receiving billions of dollars in corporate investment, as seen with Microsoft’s several billion-dollar investment in ChatGPT. It isn’t going away anytime soon as it does present itself as potentially providing great utility to society.

In Italy, the AI chatbot company Replika was ordered to “stop processing Italians’ data effective immediately” because it posed “too many risks to children and emotionally vulnerable individuals.” This program was initially developed to provide people with AI-simulated “friends” they could banter with online, but it quickly evolved into a service used by adults and children alike to send and receive sexually explicit messages back and forth with artificial intelligence. Because of the “factual risks” Replika poses to people, the company could lose “roughly four percent” of its annual global turnover.

As is the case with everything else in life, there are tradeoffs. Italy’s response to Replika shows that if this technology can’t be regulated and kept from doing psychological and cultural harm, the people who own it can at least be held accountable. If AI is the future and its utilization is going to be widely assimilated into society, there will continue to be risks. Guardrails must be placed around AI so its use doesn’t fully erode the human experience as it so clearly has the potential to do.