Even in death, Franco Harris still had an uncanny sense of timing. The demise of the Hall of Fame running back for the Pittsburgh Steelers, who passed away Tuesday night at the age of 72, comes mere days before Pittsburgh, and the nation, will commemorate one of the iconic moments in pro football history. The man who played “Johnny on the spot” to help his team to a miraculous victory half a century ago reinforced the bond between certain athletes and the cities in which they play.

For if ever a series of events demonstrated the way in which sports serve as a window into a region’s civic culture, the last days of 1972 in the seat of Pennsylvania’s Allegheny County provide as good an example as any.

Within the span of just over a week, the city of Pittsburgh went from ecstatic celebrations over an improbable — and historic — victory in football’s playoffs to losing not just a Hall of Fame baseball player but a local and national treasure. Half a century later, people from well outside the Steel City can and do commemorate both occasions — one of them epic, the other tragic.

A Historic Catch

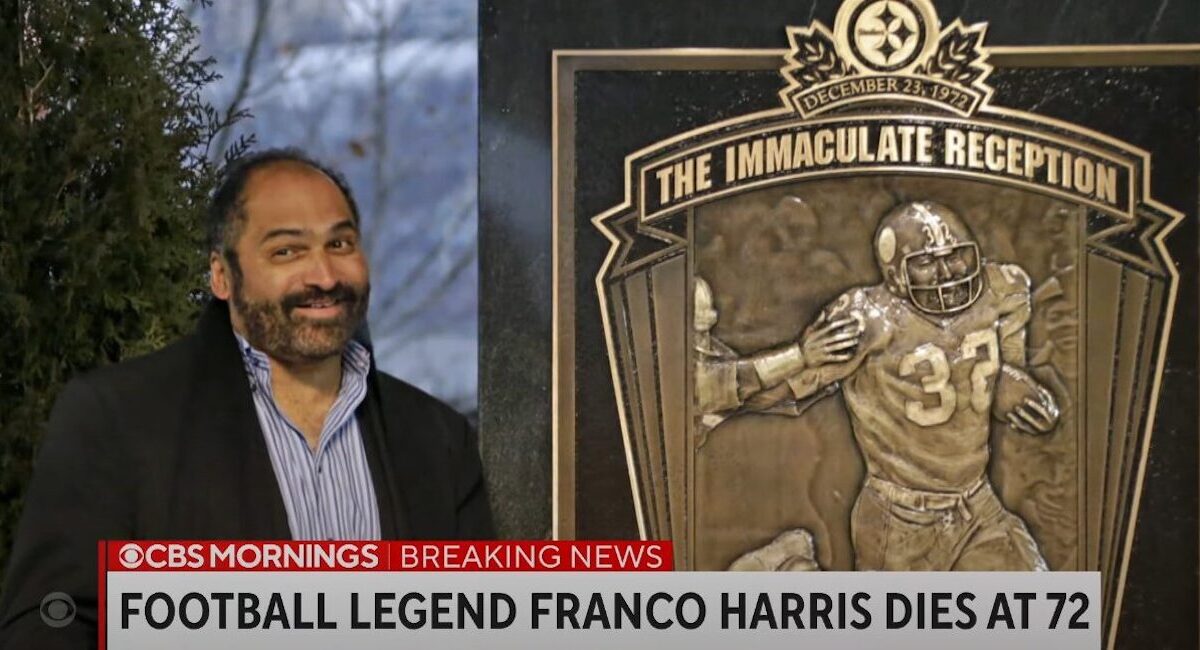

It stands as perhaps the most famous play in professional football history and certainly the one with the best nickname. On Dec. 23, 1972, the “Immaculate Reception,” which topped the NFL’s 100th-anniversary list of greatest plays, changed the trajectory of a previously hapless Pittsburgh Steelers franchise.

Trailing the Oakland Raiders by one point in a playoff contest, but with mere seconds left in the game, Steelers quarterback Terry Bradshaw hurled a desperation pass in the direction of running back “Frenchy” Fuqua. The ball caromed — off of Fuqua and/or Raiders defensive back Jack Tatum — straight into the hands of Harris, who sprinted down the sideline for the touchdown that won the game for Pittsburgh.

In addition to the seemingly impossible and dramatic outcome, the reception also brought with it controversy. Under NFL rules at the time, if the ball had caromed solely off of Fuqua — as opposed to Tatum, or both Fuqua and Tatum — Harris’s catch would have been illegal. Officials waited several minutes, and the head referee ducked into a dugout at Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium before awarding the Steelers the touchdown.

In an era before the NFL or other sports leagues authorized instant replay and before ubiquitous slow-motion cameras allowed for the dissection of plays from every angle, the “Immaculate Reception” holds its lure in part because no one really knows exactly what happened — who did or did not touch the ball during that fateful carom. Raider players have maintained for decades that Fuqua alone touched the ball; Steelers enthusiasts, the opposite. The NFL even got a professor of physics (who, it must be noted, worked for a Pittsburgh-based university) to analyze the ball’s trajectory in the hopes of bringing an end to the controversy. Spoiler alert: It didn’t.

But neither side can dispute the way in which the “Immaculate Reception” marked a turning point in the Pittsburgh Steelers’ fortunes. The game served as the franchise’s first-ever playoff win — in their 40th season of operations. Thanks to the “Reception,” the team gradually shed its image as loveable losers, going on to win four Super Bowls later in the 1970s.

The site of the “Reception,” Three Rivers Stadium, was imploded in 2001. But at the successor stadium, Heinz Field, the Raiders (who have since moved to Las Vegas) and Steelers will convene on Saturday night to renew their rivalry and commemorate one of the most famous plays in football history.

Near Heinz Field, a statue marks the exact spot where Harris caught the famous pass half a century ago. It stands as a testament to the athletic greatness that awaited the Steelers following Harris’s dramatic touchdown and the controversy surrounding the play that persists to this day.

A Tragic Loss

Not two weeks after celebrating the highs of a historic victory, the city of Pittsburgh lost one of its icons and an icon of American sport. Roberto Clemente perished on the evening of Dec. 31, 1972, in an airplane accident off the coast of his native Puerto Rico.

The accident ended the Hall of Fame career of a 15-time All-Star, a right fielder who won 12 Gold Gloves for his fielding abilities and incredibly accurate throws. Clemente notched his 3,000th — and, as it happens, final — hit just three months before his death, joining an elite list of players reaching that milestone.

While playing all 18 seasons in Pittsburgh, Clemente faced challenges as one of the first prominent Caribbean and Latin-American players in Major League Baseball. Persistent back and neck pain from a 1954 accident when a drunk driver plowed into his car prompted some sportswriters to (wrongly) think him lazy. But in time, the Pittsburgh community grew to appreciate the talent and heart of their star.

Despite the strength of his achievements on the field, Roberto Clemente’s greater accomplishments came when he was off the diamond. He served his country by spending six years in the Marine Corps Reserves. And he returned to Puerto Rico every offseason, keeping his links to the land of his birth and working to support his Latin American brethren.

That spirit of service led to his untimely demise. On Dec. 23, 1972 — the very day of the “Immaculate Reception” — a massive earthquake struck Nicaragua. Clemente immediately began organizing rescue supplies for the victims but feared (correctly) that the corrupt government of Nicaraguan President Anastasio Somoza would siphon off the relief supplies.

Thinking Somoza and his henchmen were less likely to steal from Clemente himself, the star decided to accompany the next shipment of relief supplies to Nicaragua. His spirit of service, and dedication toward others, prompted Clemente to hop on board the rickety, overloaded DC-7 that took off on New Year’s Eve, 1972. The plane soon disappeared from radar, and the bodies of Clemente and four others on board were never recovered amid the wreckage found in the Caribbean.

American Experience ended its biography of Clemente with a quote from one of his friends that elegantly captured the man’s legacy: “If he had died as a player, only the sports fans would have remembered him. But while helping others, he would be remembered as a humanitarian.”