As they work to ram through their massive tax-and-spending bill, Democrats suddenly want to take credit as fiscally responsible deficit cutters:

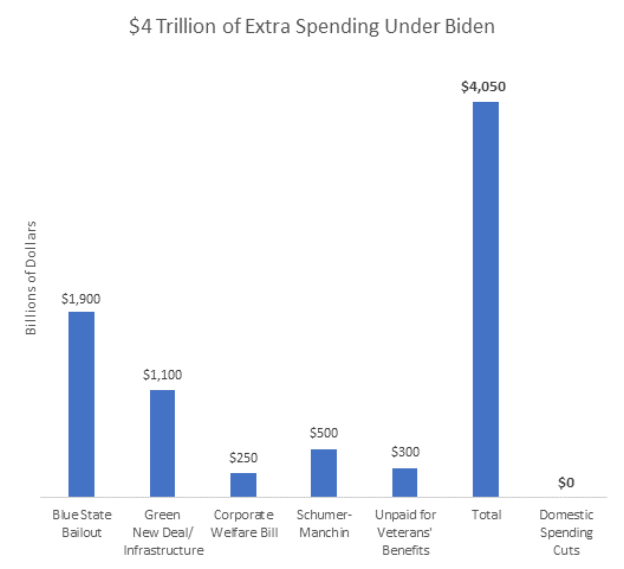

Forget for the moment that the original Build Back Better legislation proposed roughly $5 trillion in budget-busting spending. Also ignore that, notwithstanding the inflated $4 trillion cost of the President Trump tax bill quoted in Murphy’s tweet, Republicans also have a far-from-stellar record at cutting spending.

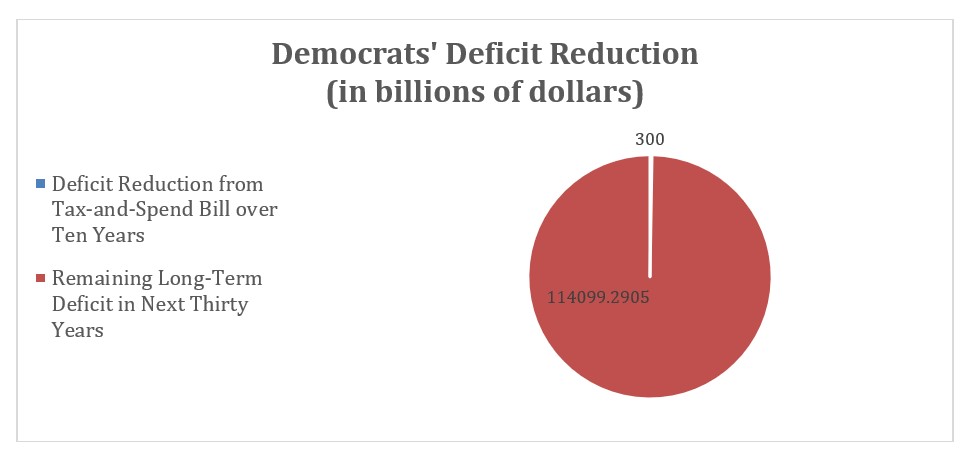

But even assuming the Democrat bill reduces the deficit by the $300 billion over a decade that Sen. Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., alleges, take a guess at the size of the collective deficits our federal government will run over the next three decades. The total: A staggering $114.4 TRILLION. That’s $114,400,000,000,000 in unpaid-for federal spending.

This budget bill, even if enacted and implemented as Democrats claim, would reduce the cumulative deficits over the next three decades to “only” $114.1 trillion. In other words, it would allegedly reduce our collective deficit by a currently estimated 0.3 percent. Here’s a visual representation of that “deficit reduction” even if Democrats’ claims come true (a pretty shaky assumption):

Given this meager impact on an overall dismal budgetary picture, perhaps Murphy should stop bragging about Democrats’ supposed “fiscal responsibility.”

New Budget Office Analysis

The $114 trillion figure comes from a new report by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) regarding the nation’s long-term budget outlook. Ironically enough, as Schumer and Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., were working behind closed doors to put the final touches on their tax-and-spending spree last Wednesday afternoon, CBO was releasing a report quantifying the vastness of the fiscal gap we face in the coming years.

CBO estimates deficits will go from 3.9 percent of GDP in the fiscal year ending Sept. 30 to 11.1 percent of GDP by 2052. Multiplying CBO’s estimated annual deficits as a percentage of the economy by their estimates of GDP in each year provides the $114 trillion figure for our cumulative deficits from now through 2052.

Most ominously, CBO believes that net interest costs will rise sharply, from 1.6 percent of GDP in the current fiscal year to 6.2 percent by 2052. Like a snowball rolling down the proverbial hill, or someone who keeps paying the minimum on his credit card, the debt we have accumulated will require more and more resources to fund every year. Moreover, this near quadrupling of federal interest costs as a percentage of our economy means paying down government debt will squeeze out private investment—making our economy permanently less productive and poorer.

Unrealistic Assumptions

Believe it or not, the assumptions behind these CBO calculations actually make our fiscal situation look good compared to more realistic scenarios. Consider the following:

- CBO assumed that discretionary spending—that’s the portion of the federal budget that includes defense, border security, transportation, K-12 education, and most government programs beyond Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security—will decline as a percentage of GDP. However, this assumption would require a significant reduction in spending compared to the average over the past two decades. As one might expect, a budget that assumed discretionary spending would remain near historical averages would increase future deficits and debt.

- CBO assumed that revenues would increase following the expiration of many provisions of the Trump tax bill in 2025, while adding that “this upward trend [in federal revenues] does not align with experience.” If instead revenue aligned with the historical average over the past 50 years, and discretionary spending aligned with historical practice, total federal debt in 2052 would total 262 percent of GDP, rather than “only” 185 percent in the scenario cited above.

- Beginning with this year’s report, CBO used different methods for determining interest rates and the growth of health care costs in the years beyond the official 10-year budget window. Both of the new scorekeeping methods had the effect of lowering cumulative deficits in the “out years,” i.e., the second and third decade studied by CBO.

Even with a series of favorable and potentially unrealistic assumptions, the CBO report shows how debt and deficits will soon skyrocket to unsustainable levels.

Congress Needs Big Cuts, Not to Spend Like Nuts

All the talk of billions and trillions can either make one’s eyes glaze over, make one depressed, or both. But one paragraph in the CBO report puts the choices we face in more understandable and practical terms:

If lawmakers wanted debt in 2052 to remain at roughly its level at the end of this fiscal year (about 100 percent of GDP), they could, for example, cut noninterest spending or raise revenues (or do both) to reduce the deficit in each year beginning in 2027 by an amount equal to 2.8 percent of GDP, which would amount to $800 billion, or about $2,400 per person, in 2027.

In other words, if we wanted to stabilize federal debt, lawmakers would need to find budget reductions equal to $2,400 per person per year—not budget reductions per household, but for every man, woman, and child in this country. Keeping spending at that lower level would still leave the federal government with debt at historically high levels, and near the all-time high of 106 percent of GDP, set just after World War II.

Of course, spending reductions (or tax increases, or both) necessary to achieve this level of fiscal savings could well spark an economic downturn. But a CBO report released earlier this year shows that failing to act in a prompt manner will only make the problem worse, as federal debt slowly strangles the economy over time.

Unless and until Murphy wants to propose the kinds of savings contemplated in the CBO report—that’s $800 billion of deficit reduction in one year, rather than $300 billion over a decade—he might want to stop preposterously claiming fiscal responsibility. Because, in the words of Winston Churchill, he and his fellow spendthrift lawmakers have much to be modest about.