Since a federal judge struck down the federal mask mandate, commentators have parsed the decision from both left and right, claiming the ruling was legally suspect. While their legal arguments are wrong, at least they’re not as wrong as Anthony Fauci’s response before (where else?) the TV cameras.

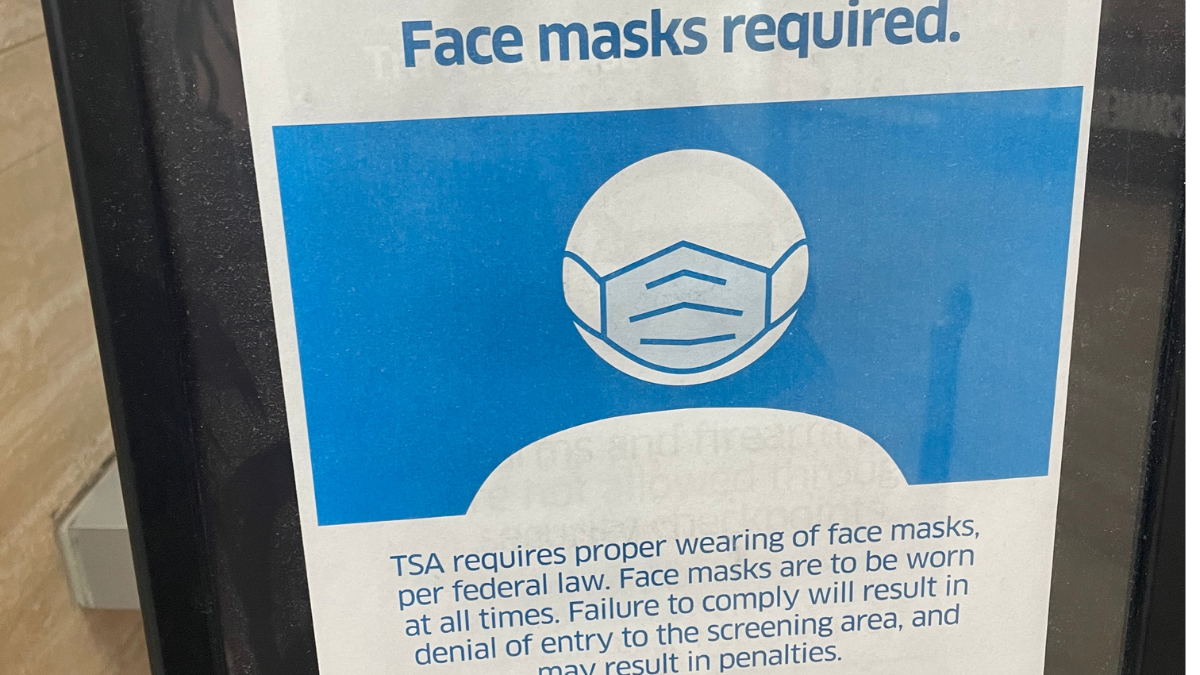

On April 18, Judge Kathryn Kimball Mizelle ruled that the Centers for Disease Control mask mandate for public transportation exceeded the agency’s delegated powers and violated the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), the law that governs rule-making by federal agencies. Mizelle found the mask mandate was not within the regulatory powers Congress granted to federal health authorities.

But even if the scope of the mandate was within the power granted by Congress, the CDC failed to follow the procedural requirements of “notice and comment,” failed to establish “good cause” for why they bypassed the notice and comment requirement, and failed to adequately explain the reasons for the mandate, as the APA requires.

Mizelle did not rule on whether the mask mandate was necessary to curb Covid-19, whether masks protect the wearer and others from Covid-19, whether the benefit of mask-wearing outweighs the risks associated with masking, and other public health considerations. In other words, Judge Mizelle analyzed the legal issues in the case; she did not second-guess the CDC’s medical judgment.

That, however, didn’t stop Fauci, a non-lawyer, from criticizing the judge’s ruling. In an interview on April 21, 2022, Fauci said the ruling set a “dangerous precedent” and opined that courts and the legal system should not be involved in public health matters. That, he said, should be left to public health experts.

Fauci apparently prefers government by experts and doesn’t understand, or chooses to ignore, that the CDC is not granted unfettered discretion by either the Constitution or Congress to make laws. The interviewer failed to challenge Fauci about his misguided view of our system of government and his promotion of the “rule of experts” instead of the “rule of law.”

Fauci was, after all, commenting on a legal matter appropriately brought before a U.S. federal court. The irony is that while the non-doctor judge did not second guess a medical question, non-lawyer Fauci was perfectly comfortable second-guessing a legal question.

Legally, the Judge Was Correct

Under Article I of the Constitution, “[a]ll legislative powers” are vested in Congress. That means Congress, not administrative agencies, has the exclusive power to make the laws.

In furtherance of that power, Congress has granted some rule-making authority to federal agencies. But Congress also spelled out in the APA the procedural steps required if an agency issues regulations that have the force and effect of law. The question before Mizelle was whether Congress delegated the CDC the authority to issue the mask mandate and, if so, whether the CDC followed the procedural steps required by the APA.

The CDC relied upon the Public Health Services Act of 1944, 42 USC § 264(a), for the authority to issue the mandate:

The Surgeon General, with the approval of the Secretary, is authorized to make and enforce such regulations as in his judgment are necessary to prevent the introduction, transmission, or spread of communicable diseases from foreign countries into the States or possessions, or from one State or possession into any other State or possession. For purposes of carrying out and enforcing such regulations, the Surgeon General may provide for such inspection, fumigation, disinfection, sanitation, pest extermination, destruction of animals or articles found to be so infected or contaminated as to be sources of dangerous infection to human beings, and other measures, as in his judgment may be necessary.

The government argued that requiring travelers to wear masks on airplanes and in transportation hubs fell within the “sanitation” methodology authorized by the statute. Mizelle was not persuaded. She found that the ordinary meaning of “sanitation” as used in §264(a) at the time the act was adopted referred to cleaning or sanitizing property by destroying or removing the contamination, in this case the Covid-19 virus. Because facial coverings do not destroy or remove the Covid-19 virus from tangible property, she held the mask mandate was not within the power delegated to the CDC by Congress.

Reasonable minds may differ on how to interpret the specific language of §264(a). The government argued for a much broader interpretation of sanitation. Nevertheless, the CDC’s authority to impose such regulations is also limited by the APA.

In other words, assuming Judge Mizelle erred in interpreting the scope of the CDC’s authority under §264(a), the APA sets out the procedural steps required to issue a binding regulation. Mizelle found that the CDC did not follow the steps required by Congress.

How the CDC’s Mask Mandate Broke the Law

First, 5 USC § 553(b) required the CDC to provide the public with notice of the proposed rule, give the public at least 30 days to submit comments, and then to consider those comments before adopting the final rule. It was undisputed that the CDC did not do any of those.

Instead, the CDC argued that the notice and comment provisions did not apply because the mask mandate was not a rule binding the public. As the court noted, “the government abandoned that untenable position on review.”

The second argument the government put forward was the mask mandate fell within the “good cause” exception to the notice and comment requirement. To invoke that exception, the law requires the agency to show that notice and comments are “impracticable, unnecessary, or contrary to the public interest.” The government’s justification for using this exception was:

Considering the public health emergency caused by COVID–19, it would be impracticable and contrary to the public’s health, and by extension the public’s interest, to delay the issuance and effective date of this Order [to provide for notice and comment].

In other words, notice and comment was not required because the CDC didn’t think it should be. Judge Mizelle found that the unsupported assertion of the CDC’s employees was not sufficient to satisfy the burden Congress placed on the agency to justify its failure to provide notice and comment before imposing the mandate on the traveling public. The rule of law cannot be ignored because some experts find it inconvenient.

The Mask Mandate Was Arbitrary and Capricious

Finally, the court found the mandate was arbitrary and capricious because the CDC did not set out their reasoning for the rule as required by the APA. Like the “because we said so” justification for ignoring the notice and comment requirements, the CDC did not explain why masking was required in some instances but not in others.

For example, the mandate created exceptions for passengers who were eating, drinking, had medical conditions that precluded them from wearing masks, and for those under two years old. There may well be legitimate reasons to draw the lines where the CDC drew them, but the law requires the rulemaking agency to explain why it drew the line where it did. Even experts must abide by the rule of law.

No, Fauci, the judge’s ruling did not create a “dangerous precedent,” it vacated the mandate because the CDC did not follow the law. Besides, if Mizelle was wrong in her legal analysis the court of appeals will reverse her; there’s a check on her authority. The dangerous precedent is Fauci’s view that experts can impose rules with no check on their authority. Our system is based on the rule of law, not the rule of experts. Even public health experts must understand that.