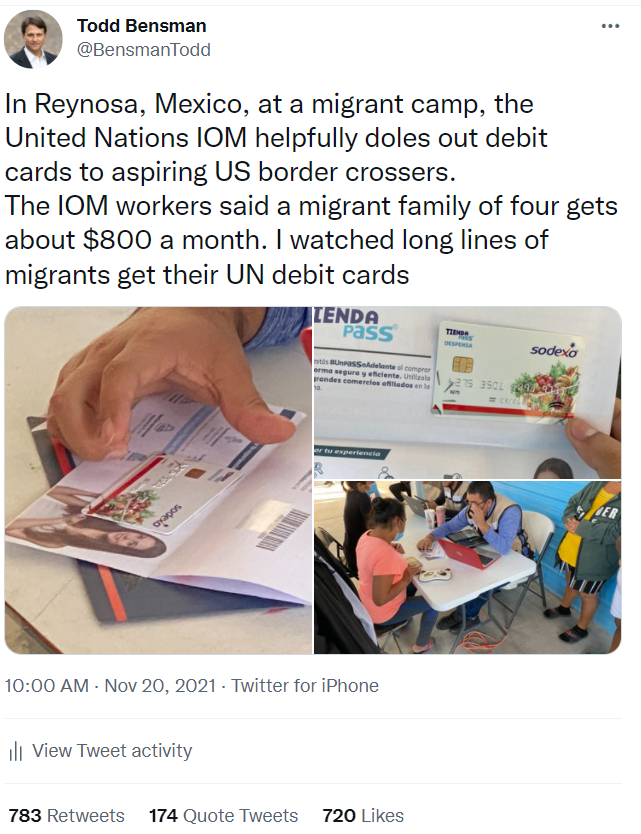

AUSTIN, Texas – During a recent trip to a Reynosa, Mexico migrant camp, I took photos of a United Nations-supported International Organization for Migration (IOM) operation to hand out cash debit cards to intending and repeat border crossers.

One of two workers at a plastic folding table inside the Reynosa camp, which was filled to capacity with at least 1,200 mostly U.S.-expelled Central Americans, said they were distributing the cards for IOM to help migrants waiting until they cross the Rio Grande at greater leisure to claim asylum, for which most will be declared ineligible years later. Many parents, for instance, got about $400 every 15 days, I was told, or $800 a month if they were still there to collect it, although the support level varied.

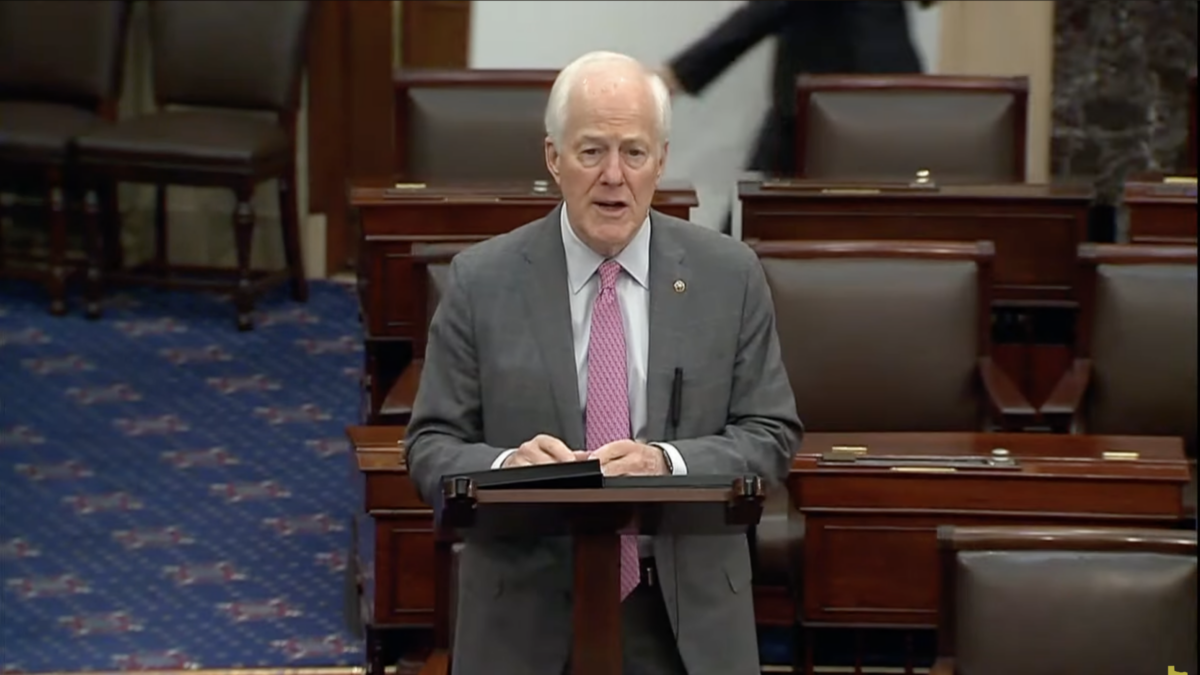

My photos of this posted to Twitter and related dispatch for the Center for Immigration Studies drew outrage among some Republican lawmakers. They saw the images as evidence that the U.S. taxpayer-funded IOM was providing material support to an ongoing mass migration harmful to America’s national interest.

A couple of weeks later, Texas Rep. Lance Gooden, R-Texas, and 11 other House Republican co-sponsors introduced the “No Tax Dollars for the United Nations Immigration Invasion Act” bill. It would prohibit the $3.8 billion in contributions currently proposed in the White House 2022 budget to the IOM and other UN-supported organizations. A Daily Caller story that broke news of the bill’s introduction quoted Gooden citing my Reynosa photos.

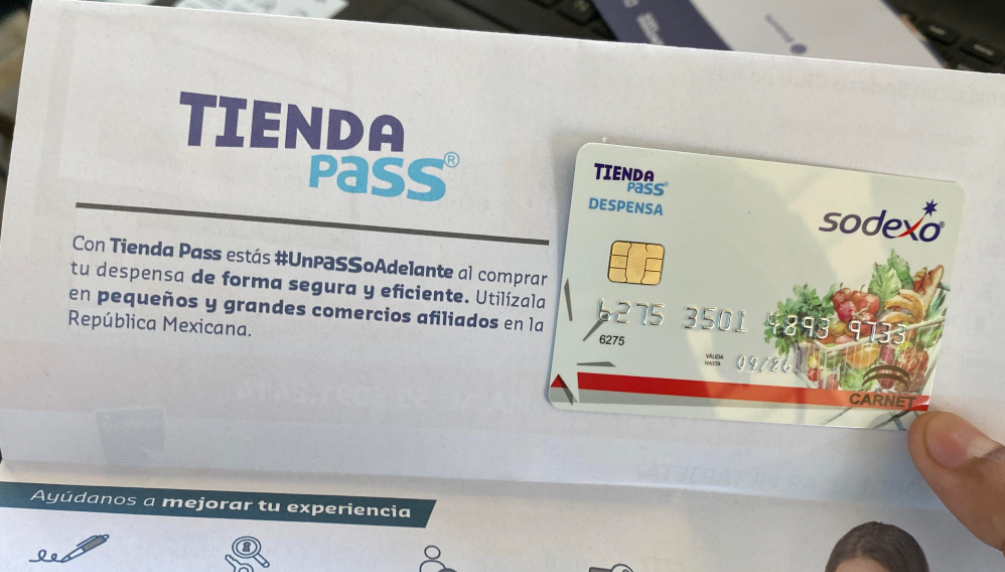

When I took the photos, I wasn’t exactly sure of exactly what I was seeing in Reynosa. But here’s what I have learned since: The money card is confirmed beyond doubt, but also “hard cash in envelopes” and “movement assistance”; and an online IOM “Emergency Manual” describes what I saw as part of a program it terms “Cash-Based Interventions,” or CBIs.

Paying People Who Illegally Enter the United States

So, for starters, country-specific IOM “Cash Working Groups” are indeed coordinating the handouts of the cash-holding plastic cards I saw (referred to as prepaid debit cards, e-wallets and e-cards) to intending U.S. border crossers in Reynosa, Mexico. But it turns out that is just an iceberg tip. The IOM is handing out cash and other material support to intending illegal border crossers in as many as 100 other shelters it helped build, expand, or supports from Central America north.

Some form of this has been around for years, but starting with a mass-migration event and Trump’s “Remain in Mexico” policy in 2019, the IOM supercharged the program and “institutionalized” it. This doubled the countries where it is used in 2020 and increased by 77 percent the number of recipients to 1.6 million worldwide, according to an annual 2020 IOM report. That would include Mexico.

The IOM Emergency Manual document says this cash assistance also includes less-seeable bank transfers, mobile transfers, and e-vouchers that go to intending illegal border crossers en route or at least temporarily blocked like many of those I saw and interviewed in Reynosa. In addition to those and the pre-paid plastic cards, the IOM says in its Emergency Manual that it also sometimes hands out “cash in envelopes (hard cash).” No details are offered on that.

Many payments are given as “unconditional; unrestricted cash transfers” for “multi-purpose use,” the manual says. Still other handouts subsidize the lodging, rent, and utilities of intending border crossers for “safe tenure, to reduce the risk of forced eviction.”

Start Tapping U.S. Taxpayers Before You Get There

Then there is “movement assistance” in the form of conditional or unrestricted cash transfers. The IOM describes this money as providing transportation access after, say a camp is closed, but also simply “to sites and other situations related to onward movement of population.”

To border hawks, all of this looks, feels, and acts like an agency providing the means for illegal border crossings. The IOM’s own stated purpose for cash-based interventions would only reinforce the perception: the money is intended to “restore feelings of choice and empowerment for beneficiaries.”

Migrant advocates defend cash support to aspiring illegal border crossers as a means to prevent death and suffering among populations they believe have no choice but to migrate and would whether or not any UN agency helps out. But the legitimate flip side of that claim is that cash in envelopes or in e-wallets—filled in part by U.S. taxpayer money—can also be said to enable, sustain, or even entice many driven not by urgent dangers but by a desire for better jobs amid reports that Americans would let them in.

Spending U.S. Money to Encourage ‘Invasion’

An aggravating irony among the fast-expanding coterie of Republican congressional critics of the UN largesse is that U.S. taxpayer money is being spent in contravention of American immigration law and national interest in controlling the border against economic migration.

“All of this sounds like they’re using U.S. tax dollars to encourage this invasion into the nation, and it seems strange to me that we would support an organization that encourages and funds this,” Gooden told me. “It’s totally crazy. I am baffled that there’s not more outrage but I think the lack of outrage is due to the lack of knowledge.”

While it may be true that IOM money relieves the suffering of intending border crossers, it is just as arguably true that it creates financial breathing room they need to prepare for more opportune crossing moments. The money enables that highly desired payoff, rather than a forced trip home for lack of funds after, say, an expensive smuggling journey that ended with U.S. expulsion. Those ones arrive in villages with a deterring don’t-try-this message to friends and neighbors.

Regarding the importance of such messaging in the development of mass migration crises, I’ve never met one who didn’t carry a cell phone connected to Internet social media. In interviews with perhaps hundreds of migrants in Mexico and beyond, I learned that this live-time social media grapevine constantly sings with news from the trail upstream that directly informs decisions downstream as to whether to launch north or remain in place.

So when word of these IOM cash, lodging, and transportation benefits spreads via social media to hometowns, friends and relatives undoubtedly feel more emboldened to invest smuggling money for their own journeys to UN waystations. Because of all this, monthly IOM cash for food, lodging, and “movement” assistance amounts to material support for illegal immigration. It influences decisions to cross.

Increasing U.S. Cash Support for Illegal Immigration

It’s unclear just how much the United States gives IOM to sustain intending border crossers until they succeed, or how many got some during 2021. But the cash giveaways have been on a steep skyward trajectory since 2019 and only show signs of continuing upward.

The public reporting as to how much the United States, through the State Department, gives IOM and how many got it is opaque at best. President Joe Biden’s 2022 budget calls for $10 billion in humanitarian assistance “to support vulnerable people abroad.” But there’s no detailed breakout.

A Fiscal Year 2019 summary (starting page 37) by the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM), which provides U.S. funding to the IOM and many other United Nations agencies, offers one clue of the pre-expansion levels. IOM spent more than $60 million in 2019 for activities in the northern part of South America, Central America, and Mexico during the so-called “caravan migrant crisis” earlier that year, the fiscal year report said.

State Department-funneled money helped IOM provide 29,000 people in the Western Hemisphere with cash and voucher assistance and supported 75 shelter waystations, the State Department report states on page 42, much like the one I visited in Reynosa. Along the northern border of Mexico in July 2019, at the height of a “caravan” crisis, the IOM provided 600 beds and essential items to the Mexican government and helped it expand existing shelters and build new ones to accommodate the “asylum seekers.”

This came as a response to the Trump administration’s “Remain in Mexico” turn-back policy. That deported economic migrants trying to abuse the asylum system, while others chose to wait for Democrats to take the White House in November 2020—a sound bet, it turned out.

The IOM decided to increase the size and scope of the program after 2019, even after President Biden took office and ended Trump’s “Remain in Mexico” policy. The extent is unclear, but the IOM institutionalized cash handout programs in Panama, El Salvador, and Mexico in 2020. Ambiguously, the IOM’s annual 2020 report on the program showed only that it gave cash to somewhere between 10,000 and 100,000 people in Mexico that year.

Whatever the recipient numbers since 2019, the IOM clearly intends an upward trajectory for the cash giveaways. The IOM’s Emergency Manual stated several times it would do so in alignment with a fairly recent pact among an international consortium of organizations known as The Grand Bargain, of which the IOM is a signatory. The Grand Bargain pact dates to 2016.

An Inter-Agency Standing Committee Grand Bargain website reports that number 3 on the objectives list is “Increase the use and coordination of cash-based programming.” A November 26, 2021 Grand Bargain caucus on cash coordination had all principals agree to increase the use of cash “beyond current low levels” through the use of even more means of delivery.

The section’s first line starts out using familiar language seen in the IOM’s Emergency Manual: “Using cash helps deliver greater choice and empowerment to affected people…”

Here’s the problem: with the greater choice and empowerment that IOM money can buy, aspiring migrants are able to remain within striking distance of the southern border to choose the time of their inevitable illegal border crossings. No one should wonder why border hawks hate this system and open borders advocates love it.