Many on the right have argued in recent years that Democrats are trying to destroy, abolish, or squeeze out of existence the suburbs and that we should rally the troops to stop them. Tucker Carlson, for example, made the case on a June 29 episode of his Fox News show that Democrats want to make the purple suburbs more like the blue cities “to make the country a one-party state.”

To prevent this, Carlson and company want to protect single-family zoning from being eliminated through federal incentives, like those that exist in the infrastructure package currently being debated in Congress.

For reasons including debt, inflation, and respect for local control, let’s all agree that the federal government shouldn’t spend any money in this bill on carrots to encourage certain zoning. But that doesn’t mean the current “conventional suburban development” model, often called urban or suburban sprawl, is conservative. In fact, this model violates multiple core conservative principles — it breaks with tradition, wastes taxpayer money, limits property rights, is a major factor in the deterioration of our community life, and largely ignores aesthetics.

Suburbs (in their traditional balance to urban and rural areas) are a vital part of a metro region, so no one should abolish them. But the danger at the moment is not that suburbs are on the verge of disappearing. On the contrary, urban and rural areas are increasingly being gobbled up by suburbia, and this shouldn’t be seen as a victory for the right.

Suburbia Is Undeniably Ugly

The first complaint for conservatives, who should pursue truth, beauty, and goodness above all else, is these neighborhoods are mostly ugly. Sure, that may seem like a subjective statement, but think of the most beautiful (manmade) places you’ve ever traveled. I’m guessing what comes to mind isn’t the disorienting monotony of suburbia, with its office complexes, McMansions, and strip mall parking lots.

It’s probably somewhere more like Charleston, South Carolina, (ranked America’s favorite city in the country seven years running) or another city that uses the “traditional neighborhood development” model — with a walkable downtown, a mix of uses, a simple street grid, and an attempt at “vernacular” architecture. Many of these places are old, but they don’t have to be; they just have to be built using the basic best practices of placemaking embraced in most times and places before the mid-20th century.

So, rather than seeing modern suburbia as the traditional American dream, we should be clear that it is a new model, begun after World War II, and a major break with the past. Conservativism relies on customs that slowly develop and are tested by time. The traditional town- and city-planning models were just that.

Before WWII, whether you were in New York City’s Little Italy or some Mayberry-like small town, they were designed so generations of families could live and die there. There was housing for all ages and income levels, and many buildings had a diversity of uses, so you could work, live, play, worship, and go to school all within a few blocks. Then outside of this density were suburbs, and outside that, rural areas.

Zoning Gone Wrong

But city planners’ obsession with micromanaging through zoning led to a separation of uses when developing land, which was made possible by the growing ubiquity of the automobile. One area would be zoned only for housing, another only for retail purposes, another for schools, another as a business park only for offices.

This is where the fight over “single-family zoning” comes in. In many cities, the bulk of land is zoned in a way that only detached houses with large-sized lots can be built. If you want to build townhouses, a corner store, a duplex, or, God forbid, an apartment complex, good luck.

Carlson argues that if the federal government pressures towns to scale back single-family zoning, you “are no longer in charge of how large your lot sizes can be.” But what he really means is, you will no longer be in charge of how large your neighbor’s lot size will be.

Are conservatives only against impositions on freedom and property rights from the federal government, while local governments should have absolute power over the size and use of all property in their jurisdictions? To paraphrase Mel Gibson in the “The Patriot,” who was paraphrasing American royalist Mather Byles, “Would you tell me, please, Mr. Carlson, why should I trade one tyrant 3,000 miles away, for 3,000 tyrants one mile away?”

Rather than being a byproduct of American freedom, endless suburbia has arisen because local governments have forced property owners to only build for one type of use — single-family housing — in the vast majority of their zoning.

Carlson’s native San Francisco Bay Area of California is a great example. More than 80 percent of its land is zoned for “single-family housing.” In San Jose, where Silicon Valley is centered, it is 94 percent single-family zoning. Is it any wonder that nobody can afford to live there and people are leaving in droves? If it’s illegal to build up and fill in spaces to create density close to where people work, all you achieve is traffic and boring developments for hours in all directions.

Then people have to decide whether to live in an inner suburb (formerly known as a city), where they can get a sad-looking 816 square-foot-house for $800,000 or an outer suburb (formerly known as the countryside), where for the same price they may be able to get twice the square footage but will have to spend hours more of their week behind the wheel. It’s no wonder that many gainfully employed Bay Area residents decide to just get an RV and park it somewhere close to work. The fear shouldn’t be that we’re at risk of “abolishing the suburbs” but that we’re abolishing everything else.

The Senseless Fight Against Apartments

Part of the fear from the Sprawl Defense League (and the major objection I see in conservative articles on the topic) is that if you get rid of the mandated single-family zoning in their area, then a giant apartment complex full of gangs and crime will pop up on the empty lot in their cul-de-sac. As Carslon put it, “If they wanted to live next to Section Eight housing, they would have stayed in the city in the first place.”

But in many cases, they do live in the city; they just don’t want to admit it. San Jose is apparently happy to approve bringing in 250,000 high-tech jobs, just not to give these (mostly foreign-born) workers anywhere to live.

Also, even if an area did decide to reduce its percentage of single-family housing, developers would still be highly unlikely to choose expensive land around a wealthy suburban development to build low-income housing. They’ll continue to find the cheapest land for such projects, as they always have. But a major reason lower-income people are concentrated in complexes like that in the first place, rather than spread throughout the region, is precisely because so few areas of American cities allow development of low-income housing.

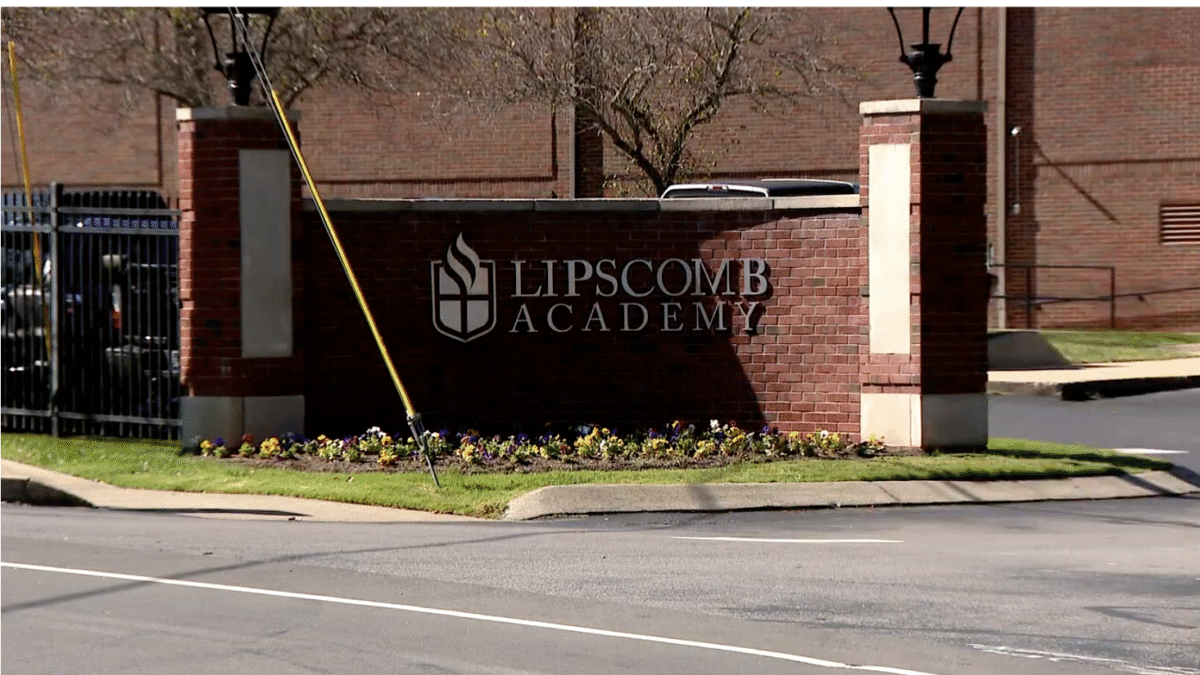

In my home state of North Carolina, our biggest city, Charlotte, currently has 84 percent of its land zoned for single-family housing. Much of the rest is for commercial or other purposes, so the segment that allows multi-family housing like apartments has to concentrate virtually all of the city’s poorer residents. If rates of social dysfunction are generally higher among the poor, what effect do you think cramming them all in a few blocks of the city will have?

Cheaper housing is obviously not just used by the criminals that suburban residents often fear. Some of it is used by older, retired people on a fixed income. Some of it is used by young adults, like recent grads or newlyweds, who haven’t had a chance to build up much wealth yet. Some of it is used by recent immigrants supporting families.

Some of it is used by “creative types,” like artists and writers, who don’t have a lot of money, but also don’t pose much of a threat. By legalizing other forms of development, these lower-income residents will not be forced to live in dangerous areas, and criminal elements won’t be concentrated in areas where lawlessness then takes over.

Sprawl Hurts City Budgets and Communities

We can’t even really make the fiscal argument on this one as conservatives, because allowing a mix of uses and denser development around urban centers is much more efficient on city budgets. Municipal governments are having to extend their infrastructure further and further out to provide services when the same development could have been built where the infrastructure already exists if more density were allowed.

A federal study found that conventional suburban development is between 32 percent and 47 percent more expensive than building the traditional way. Sprawl also requires massive highway projects to constantly be increasing capacity in new areas, another expense of this CSD model that shouldn’t be overlooked.

The last point, and one that will probably appeal more to social conservatives than fiscal conservatives, is that sprawl destroys our sense of community. If you live in one place, work in another, shop in another, exercise in another, and between each activity you need to get back in your car and drive miles away, you’re not rooted anywhere.

This is likely part of why Americans no longer know their neighbors or have many (or any) friends (especially men). It’s also likely part of why they no longer join churches or community clubs. It’s impossible to have a sense of pride in place or create real community as a collection of isolated transients who are shut in our homes when we’re not behind the wheel.

It’s true there are a lot of progressives pushing for the same “traditional neighborhood design” elements that I described — density near urban centers, multi-use zoning, walkable neighborhoods etc. But this is one issue where you will find very odd alliances, with a variety of left- and right-wing types on all sides.

Also, just because some on the “other side” are for something doesn’t mean we need to reflexively fight it. Many on the left who care about this issue seem to be motivated by their belief that this model is better for the environment and that it makes affordable housing more available and dispersed.

Those are small concessions for getting more efficiently run local governments, more beautiful towns and cities, less traffic, less crime from concentrated poverty, more freedom to use our property as we wish, and stronger community life.