The Washington Post was busted for publishing fabricated quotes from an anonymous source, attributing them to a sitting president, and using those quotes as a basis to speculate the president committed a crime. The invented Donald Trump quotes, which related to a fight over election integrity in Georgia, were cited in Democrats’ impeachment brief and during the Senate impeachment trial.

But the fake quotes, bad as they were, are just one of many ways the media have done a horrible job of covering election disputes in the state.

According to the media narrative, the Georgia presidential election was as perfectly run as any election in history, and anyone who says otherwise is a liar. To push that narrative, the media steadfastly downplayed, ignored, or prejudiciously dismissed legitimate concerns with how Georgia had run its November 2020 election and complaints about it.

That posture was the complete opposite of how they were reporting on Georgia elections prior to Democrats performing well in them. In the months prior to November, some media sounded a bit like Lin Wood when they wrote about Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, Dominion Voting Systems, legal challenges in the state, and Georgia election integrity in general.

How Media Talked About Georgia Before Biden Won

“Georgia’s Election Mess: Many Problems, Plenty of Blame, Few Solutions for November,” read the June 10, 2020, New York Times headline of a story by Richard Fausset and Reid Epstein about the “disastrous primary election” in June that was “plagued by glitches, but Democrats also saw a systemic effort to disenfranchise voters.”

Citing irregularities with absentee ballots and peculiarities at polling sites, the authors said Georgia’s “embattled election officials” were dealing with a voting system that suffered a “spectacular collapse.” They said it was unclear whether the problems were caused by “mere bungling, or an intentional effort” by Raffensperger and his fellow Republicans in the secretary of state’s office.

“Georgia’s troubled system” would be exacerbated by voting by mail and the increased burden of handling absentee ballots, the article said. The “trouble that plunged Georgia’s voting system into chaos” was related to its Dominion Voting Systems, “which some elections experts had been sounding alarm bells about for months.” Indeed they had!

“Georgia likely to plow ahead with buying insecure voting machines,” wrote Politico’s Eric Geller in March 2019 about the plan to replace voting machines. He said cybersecurity experts, election integrity advocates, and Georgia Democrats had all warned about the security problems of the new machines, which would be electronic but also spit out a marked paper ballot.

“Security experts warn that an intruder can corrupt the machines and alter the barcode-based ballots without voters or election officials realizing it,” he wrote. It was alleged that a “meaningful audit” was “impossible.”

When Georgia picked Dominion Voting Systems in August 2019, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution warned “critics say the system will still be vulnerable to hacking,” citing high-profile hacks of Capital One and Equifax, as well as the online attacks on Atlanta and Georgia courts. “Election officials will have to be on guard against malware, viruses, stolen passwords and Russian interference,” the article continued. Yes, Russians.

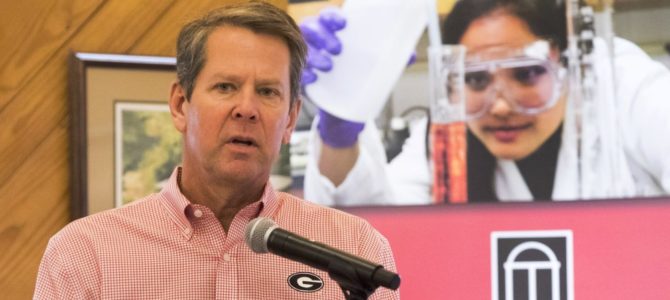

“Georgia in Uproar Over Voting Meltdown,” The New York Times proclaimed in a June 9, 2020, story, citing problems with Dominion Voting Systems and Raffensperger’s management of the election. “The machines bought by the state last year were instantly controversial. Security experts said they were insecure. Privacy experts worried that the screens could be seen from nearly 30 feet away. Budget hawks balked at the price tag. And one of Dominion Voting Systems’ lobbyists, Jared Samuel Thomas, has deep connections to Gov. Brian Kemp, the Republican who defeated Ms. Abrams in 2018,” the article read.

Washington Post went with “As Georgia rolls out new voting machines for 2020, worries about election security persist,” which said, “election security experts said the state’s newest voting machines also remain vulnerable to potential intrusions or malfunctions — and some view the paper records they produce as insufficient if a verified audit of the vote is needed.”

If critics on the right were to restate these complaints now, it is likely that tech platforms would ban them or otherwise constrain their free discussion. The same media outlets would likely characterize these claims and concerns as unfounded.

‘Sue and Settle’ Smuggles In Major Change to Mail-In

Democrats use various strategies to implement changes to voting laws in order to limit election integrity or make it more difficult for election overseers and observers to detect election fraud. One of the approaches is termed “sue and settle.”

Perkins Coie, the law firm that also ordered what became the Russia collusion hoax against Trump in 2016, runs an extremely well-funded and highly coordinated operation to alter how U.S. elections are run. The firm will sue states and get them to make agreements that alter their voting practices.

Marc Elias, well known for his role in the Russia collusion hoax and other Democrat operations, runs the campaign to change voting laws and practices to favor Democrats. Perkins Coie billed the Democrat Party at least $27 million for its efforts to radically change voting laws ahead of the 2020 election, more than double what they charged Hillary Clinton and the Democratic National Committee for similar work in 2016. Elias was sanctioned in federal court just yesterday for some shenanigans related to a Texas election integrity case.

In March, Raffensperger voluntarily agreed to a settlement in federal court with various Democrat groups, which had sued the state over its rules for absentee voting. The end result was a dramatic alteration in how Georgia conducted the 2020 election.

Republicans were not party to the agreement, despite their huge interest in the case. The agreement explicitly states that neither Raffensperger nor the Democratic groups who sued him take a position on whether the laws and procedures being changed were constitutional or not.

Democrats’ high-powered attorneys introduced several significant changes, such as the opportunity to “cure” ballots. That means that when an absentee ballot comes in with problems that would typically lead it to be trashed, the voter is instead given a chance to “cure” or correct the ballot. It also said Democrats would offer training and guidance on signature verification to county registrars and absentee ballot clerks.

Most importantly, the settlement got rid of any meaningful signature match. The law had previously required signatures to match the signature on file with the Georgia voter registration database. But the settlement allowed the signature to match any signature on file, including the one on the absentee ballot application. That meant a fraudulently obtained ballot would easily have a signature match and no way to detect fraud.

The ballot also could only be rejected if a majority of registrars, deputy registrars, and ballot clerks agreed to it, another burden that made it easier to just let all ballots through without scrutiny. It made a huge difference in how many ballots were rejected.

Raffensperger’s decision to voluntarily agree to such a dramatic change in the rules of the game without input from the Republican Party of Georgia, much less the Republican National Committee, angered many Republicans, including Sens. Kelly Loeffler and David Perdue, as they learned about it following the November 2020 election. Other Republicans felt he harmed election integrity by mailing out millions of absentee ballot applications, ostensibly because of health concerns related to COVID-19.

Election Day Drama

This brings us to election day. Because so many people had voted by mail or otherwise early, the in-person voting was fairly routine with just a few problems here and there. But one major problem was with counting votes.

A major processing center in Fulton, the state’s most populous county, claimed at one point to have trouble counting ballots in the evening because of a burst pipe or even, some officials said, a water main break. It turned out it was actually a minor urinal leak that had occurred that morning and hadn’t really disrupted anything.

Things only got weirder. That night, an election official curiously announced that they were closing up shop for the evening, even though there were tons of ballots left to count. As workers closed their counting operations and many began to leave, the news media and other election observers left. The news media reported they’d been told the ballot counting would stop.

But even though Fulton publicly said they were stopping the count, they didn’t stop counting ballots. Republicans who were already frustrated that they weren’t near enough to properly observe the counting were outraged and cried foul when they discovered they’d been misled and encouraged to leave.

Election officials denied wrongdoing. A video came out corroborating the claims of Republican poll watchers and the media about being told the counting would stop. The video also showed ballots being pulled out from under a table, and other suspicious actions that led many observers to question the integrity of the operation. Fulton County and Georgia secretary of state officials pooh-poohed the concerns or claimed, without providing a report or substantive rebuttal, that they’d looked into the situation and found nothing problematic.

For context, the shutdown — or not — of the counting of ballots was at the point in the evening when people nationwide were realizing that the media’s polls purporting to show that Biden would win the election significantly and easily were false. Trump had won Florida big. He had won Ohio big. He had won Iowa big. He was performing better than the polls had told people he’d perform. And he was up big in Georgia, too.

Many days after election day, with ballots taking an extremely long time to count, Biden began taking a small lead in the Georgia race. A “secret,” “well-funded cabal” of left-wing groups, as Time magazine would later describe them, had told allies in the media to prepare for a situation where Trump was ahead bigly on election night but Biden pulled ahead as the days dragged on. It was part of the Democrat strategy.

But for Republicans, already concerned about the inherent lack of election integrity associated with mail-in ballots, the questionable security and chain of custody problems associated with rampant use of ballot drop-boxes, the large outside funding of vote processes by tech oligarchs, and all the other problems wrought by voting and counting ballots over a period of many weeks, if not months, the situation was deeply alarming.

Even without all these changes, average Americans’ ability to trust an election is free and fair is one of the most important and basic things that preserves the republic. In 2020, election officials who were introducing radical changes at the same time scrutiny was being done away with were playing with fire.

All that being said, Biden was looking like he won Georgia by enough of a margin to make any challenges a heavy lift.

A Serious Lawsuit Is Filed

While conspiracy theories about election fraud went wild during this time — ranging from The New York Times’ claim that there was no election fraud anywhere in the entire country to dramatic claims of a global conspiracy involving Venezuela and voting machines — the Trump campaign’s official claims in its lawsuit filed on Dec. 4, 2020, were sober and serious. They weren’t alleging foreign meddling or outside hacking, as The New York Times, Washington Post, Politico, and Atlanta Journal-Constitution warned just months earlier were serious concerns.

The Georgia Supreme Court had previously ruled that challengers to an election don’t need to show definitive fraud with particular votes, just that there were enough irregular ballots or violations of election procedures to place doubt in the result. Judges never want to overturn the results of an election, but under Georgia law, the remedy for showing enough problems to cast doubt was that a new election be held. One was already scheduled for early January for Senate runoff races. Trump’s lawsuit argued that it appeared votes had come from:

- 2,560 felons,

- 66,247 underage registrants,

- 2,423 people who were not on the state’s voter rolls,

- 4,926 voters who had registered in another state after they registered in Georgia, making them ineligible,

- 395 people who cast votes in another state for the same election,

- 15,700 voters who had filed national change of address forms without re-registering,

- 40,279 people who had moved counties without re-registering,

- 1,043 people who claimed the physical impossibility of a P.O. Box as their address,

- 98 people who registered after the deadline, and, among others,

- 10,315 people who were deceased on election day (8,718 of whom had been registered as dead before their votes were accepted).

Unlike so much of the Trump campaign’s legal efforts, outside observers agreed that this lawsuit was serious:

The 64-page complaint is a linear, cogently presented description of numerous election-law violations, apparently based on hard data. If true, the allegations would potentially disqualify nearly 150,000 illegal votes in a state that Biden won by only 12,000.

But as legitimate as the lawsuit was, it entered a Kafka-esque world where it couldn’t get heard.

The election code in Georgia requires that an election contest has to be served to defendants by the sheriff. The clerk is supposed to quickly give special notice to the relevant sheriffs that it needs to be served, since election lawsuits need extremely quick resolution and require a hearing within 20 days.

Lawyers for Trump had to keep asking the clerk to give that special notice to the sheriffs where the defendants lived. In one case, a county sheriff waited until the end of January of 2021 before asking if he should serve it.

At the same time, all sorts of attorneys associated with Elias and Perkins Coie began filing pro hac vice requests, where you ask to appear in court for a particular trial, even though you’re not admitted to the bar in that state. The powerhouse attorneys began filing all sorts of special motions to dismiss, even before they were given permission. The Trump attorneys were responding anyway, just in case a court took those requests seriously.

Fulton County Judge Constance Russell, assigned by lottery to the case, turned out to be ineligible because the law says the judge hearing the case can’t be an active sitting judge from the county where the suit is filed. But before she left the case, she entered an interim order that the case was going to go on a normal procedural course, “which means it will not be resolved any time soon,” as the Journal-Constitution put it.

The Trump team had filed their lawsuit with an emergency temporary restraining order request to prevent certification of the election. When Raffensperger certified the election, the Trump team withdrew their motion and filed a new emergency motion to decertify.

With no hearing in sight, the Trump team — desperate to get to a court date before the Electoral College convened — appealed to the Georgia Supreme Court, asking it to grant immediate review of that interim order slow-walking the case, as well as the judge. That court said they couldn’t do anything about the interim order because they lacked final jurisdiction.

They did get a liberal senior judge from Cobb County, Adele Grubbs, to handle the case. She set a date for a hearing of Jan. 8, which was of no help to the Trump team as it was after Jan. 6, when Congress would process the Electoral College vote.

In the midst of all this, the Trump team also had a federal case before Judge Mark Cohen on Jan. 5. That case dealt with the Trump team’s view that they had not gotten their day in Fulton County Superior Court, which they perceived as a due process violation.

While he dismissed the case, noting that they’d soon have a hearing before Grubbs, Cohen also noted that the power and authority to do anything about the election dispute lies with Congress, not the court. All the lawsuits being filed over the country were being turned away by courts and dismissed for lack of standing, but this judge provided some direction by saying the power regarding contesting the 2020 election lay with Congress, and not the courts.

Following Trump’s phone call with Raffensperger’s team on Jan. 2, counsel for Raffensperger sent a letter saying that if the Trump team wanted access to the state’s data in order to determine the merits of their claims about improper voting, they would have to drop their lawsuit.

“[W]e are still willing to cooperatively share information with you outside the pending litigation on the condition that all currently pending suits against the Governor, the Secretary of State, and/or the members of the State Election Board be voluntarily dismissed. Absent dismissal, we have no choice but to remain in a litigation posture and to continue resolving these disputes in court,” wrote Christopher Anulewicz.

The Trump team discussed whether to accept the offer. They decided to opt for access to the information. A letter from a Trump attorney said the offer was accepted and that “[w]e look forward to working and meeting with” staff to “receive the heretofore withheld November 3, 2020 election data,” specifically mentioning expert reports, official election records, voter registration records, applications for absentee ballots, investigative reports, and other relevant data and information. The team suggested making a joint statement that the contest had been settled.

Raffensperger’s team opened the email immediately but waited several hours to respond, and when they did, they claimed they’d never made an offer to share information, just that they wouldn’t even consider discussing the matter unless the case was dropped.

Finally … The Phone Calls

This brings us back to the phone calls.

We now know that the account of Trump’s call to an investigator was based on false quotes. Another call with Raffensperger was also leaked to the press to harm those who opposed Raffensperger’s handling of the election, days before another pivotal election.

Much of the angst over the calls was about Trump saying he needed the secretary of state to “find” votes. This was always characterized as him asking Raffensperger to commit fraud or do something unethical. It even made it into the article of impeachment that Democrats supported.

Anyone familiar with the lawsuit knew Trump was saying his team had already “found” nearly 150,000 irregular or fraudulent votes and simply needed the secretary of state’s office to agree. He was saying they didn’t need to agree that all 150,000 were bad, just that fewer than 10 percent of them were problematic.

The secretary of state and his team kept asserting that Trump’s figures were wrong. Trump’s legal team kept asking Raffensperger to provide the state data and information that would enable them to see for themselves. For some reason, Raffensperger and his team have never been willing to share their data or reports.

Fox News’ Martha MacCallum asked Raffensperger directly if he authorized the leak of the second call, and he repeatedly refused to answer the question. The leak happened just days before a close Senate race that Republicans would lose, and Raffensperger admitted to MacCallum that it coincided with his anger at Republican Sen. David Perdue, whom he blamed for animosity directed at his wife after Perdue called for him to resign.

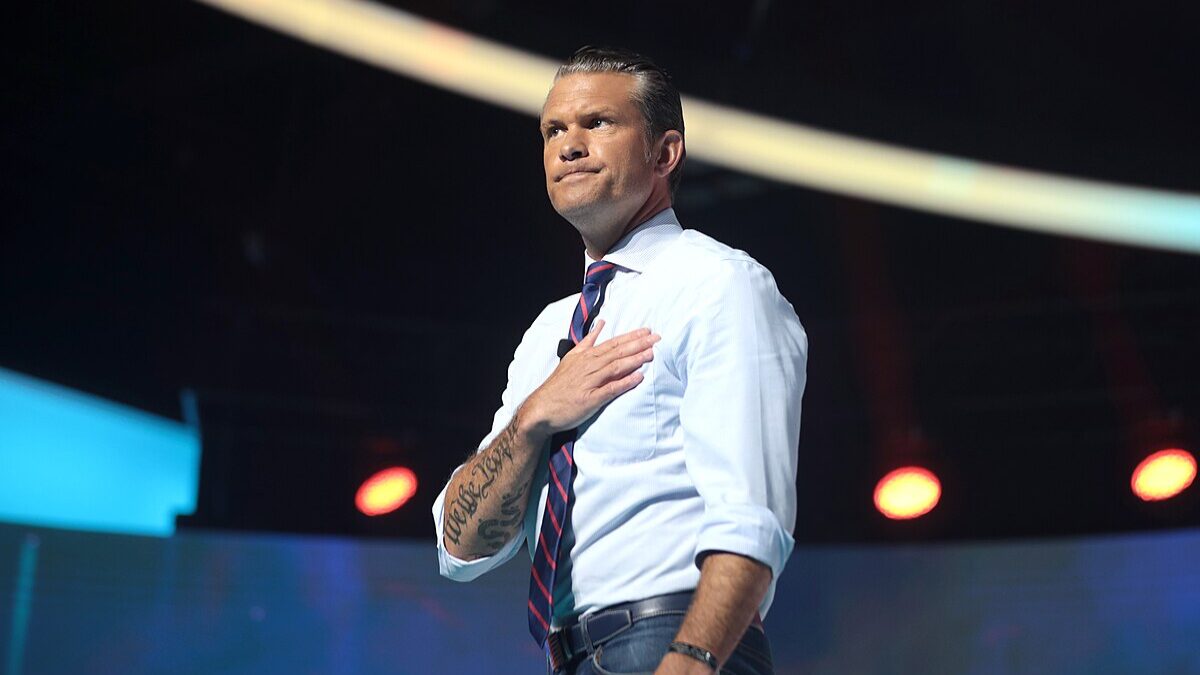

Jordan Fuchs, the deputy secretary of state, has also been fingered as being involved in both of those leaks, and the Washington Post said she agreed to be named as the source of the quotes on the former call. Fuchs has no background in election management or experience running a large organization, but she was Raffensperger’s campaign manager in 2018.

That might explain why she has run the office more as a campaign shop. Even the mildest of criticisms of her boss and their office meet brutal pushback, which has caused a serious deterioration with the legislature and many Republicans, even before the last few months.

Fuchs’s Twitter account isn’t quite as unhinged as Jen Rubin’s or Bill Kristol’s, but it’s pretty close. There are few NeverTrumpist arguments she avoids, and she shares the media’s newfound talking point that election fraud is a “big lie.” It doesn’t exactly build confidence that she knows what she’s doing, is able to separate her emotions from her work, or is capable of understanding legitimate complaints with how she manages elections.

For months, the Trump team tried desperately to get a hearing in court to make their case, and the court dockets prove that. In fact, they kept getting into trouble for how aggressively they were trying to get a hearing. Trump attorneys were on record saying they wanted the hearing so they might get access to Raffensperger’s information. The information was really what they were after.

They issued a statement after the leak to the Washington Post saying Raffensperger’s office “has made many statements over the past two months that are simply not correct and everyone involved with the efforts on behalf of the President’s election challenge has said the same thing: show us your records on which you rely to make these statements that our numbers are wrong.”

Raffensperger’s office finally said, after that infamous phone call, that they’d share state data and information “on the condition” that the Trump team drop their lawsuit. They agreed to that. Instead of turning over the data that would settle the issue, Fuchs and Raffensperger issued a press release that said, “on the eve of getting the day in court they supposedly were begging for, President Trump and Chairman David Shafer’s legal team folded Thursday and voluntarily dismissed their election contests against Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger rather than submit their evidence to a court and to cross-examination.”

It showed just how political Raffensperger and Fuchs are. While the media strongly support Raffensperger, at least until such time as a Republican wins in Georgia again, the concern about the integrity of the election remains.

Perhaps Raffensperger is completely and totally correct. But it would behoove him to share the data that proves that rather than issue antagonistic and uncharitable press releases while sitting on the information that could settle the issue.

As for the media, they’re doing what they always do — advancing a political agenda. Believing their characterization of lawsuits, phone calls, or anything else they report on is unwise.

But it wasn’t just the quotes they got wrong about Georgia. It was pretty much everything.

Update: This piece was updated to correct spelling, and that the Secretary of State’s office mailed ballot applications out to millions of Georgians.