As is clear from congressional angst over impeachment, the political and media left make little or no distinction between the unindictable, unrebutted acts attributed to President Trump in the special counsel report and proven or even probable crimes. Now there is a new legal argument taking shape that underscores the difference. Why this sudden, unusual concern with the presumption of innocence?

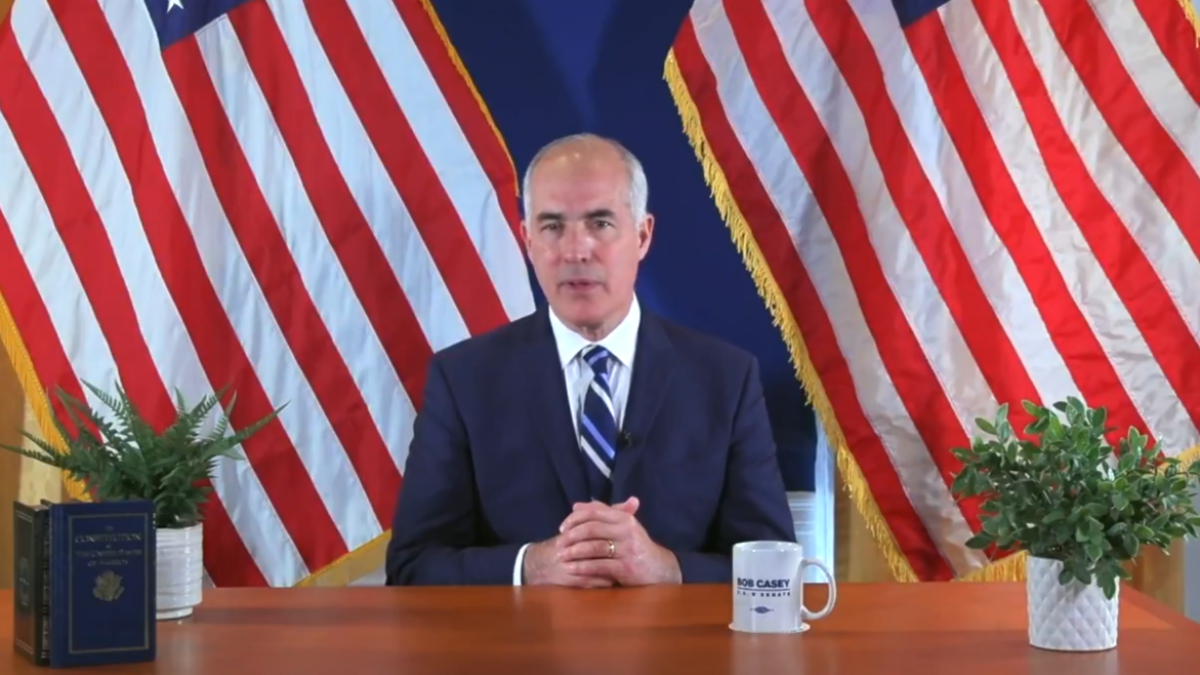

The answer is that the argument suggests how the next Democratic administration could use the Robert Mueller report’s denial of “exoneration” to game norms that would currently restrain a future Democratic president from using the justice system to prosecute Republican predecessors. Democratic candidate and Sen. Kamala Harris has already promised that, if elected president, she’ll direct her Department of Justice to investigate Trump.

In other words, if impeachment fails, Trump opponents may now have found themselves a longer-range tactic. If you look closely, however, this tactic requires them to acknowledge Mueller failed to do his job as a prosecutor.

Dems Politicize the DOJ

To be sure, this strategy, thrown out almost casually in a recent Lawfare article by Benjamin Wittes, appears to be peripheral to the author’s main point. Wittes, Lawfare editor in chief and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, was recently criticized by fellow legal star Jack Goldsmith for attempting to rehabilitate the remarkable deficiencies of the Mueller report. In the article, he seems to have accepted defeat, or at least changed tacks.

First, some context. Having blasted Trump on numerous occasions for supposedly menacing the independence of law enforcement with his public statements, including about Hillary Clinton and the special counsel’s “witchhunt,” Wittes now purports to be applying the same standards to the likes of Nancy Pelosi and Harris.

He reports being chagrined by Pelosi’s talk of jailing Trump as well as the Democratic presidential candidates’ promises to sic their future DOJ appointees on Trump after he leaves office. The latter’s promises, recall, come after Dems excoriated William Barr for daring to use the word “spying” and investigating the origins of the Russia probe, claiming Barr is toadying to Trump instead of representing the interests of the nation. Wittes calls out the Democratic presidential candidates for similarly appearing to politicize the DOJ.

Although Alan Dershowitz has penned a more nuanced analysis of the split role of the attorney general, Wittes’s discussion of the independence of the attorney general seems, at least, even-handed. One needn’t agree with the way he casts Trump’s statements to concede he’s not letting Democrats off the hook. Or so it at first seems. Problem is, Wittes’s argument is booby-trapped.

While affirming the country’s “deep tradition” of respecting electoral succession, which restrains new administrations from overturning the opposition’s previous prosecutorial decisions, Wittes invents an exception. It takes up only a paragraph. Its potential to seed new phases of the Resistance, however, gives it outsize significance. It thus deserves to be quoted in full. Stressing the importance of “peaceful transition,” Wittes says:

On the other hand, Special Counsel Robert Mueller never performed what he termed a traditional prosecutorial analysis of the evidence of obstruction, and Attorney General William Barr’s own analysis was quick and came off to many analysts (including me) as highly political. So its’s a really difficult question whether the next attorney general should regard it as a final prosecutorial judgment — and it’s probably an unanswerable question without seeing the work product that underlies Barr’s determination.

Please note, in this quote, it’s not that Mueller tried to make the obstruction statute apply under the given facts and circumstances and mangled it, it’s that he never tried. It is not Mueller who failed to carry out his mandate but Barr.

This is how the thinking goes: If Mueller never performed the requisite prosecutorial analysis and Barr only pretended to, it remains to future Democratic officeholders to see that it gets done. Thus, tried-and-true norms that constrain Republicans wouldn’t apply to Democrats, at least, not on Trump, whose egregious conduct warrants extreme measures. Sound familiar?

Dems’ New ‘Insurance Policy’

So if the question of whether Barr’s judgment should be regarded as final is, essentially, “unanswerable,” why raise it? The special counsel regulations put the final decision of indictment in the hands of the attorney general, Barr.

By suggesting Barr’s underlying analysis was “highly political,” Wittes offers a pretext for later “appealing” his resulting decision not to pursue a charge of obstruction. In the event of a Democratic win in 2020, such fake appeal would involve handing the decision over to Barr’s successor, a Democract appointee. Of course, we know that any such appointee’s redo wouldn’t be “highly political.” Of course not!

Sarcasm aside, why would challenging Barr’s finding under the guise of determining whether a prosecutorial analysis was performed (or performed sufficiently, according to Wittes’s and Mueller’s definition of “traditional”) violate deep-seated traditions any less than Trump’s statements are accused of being? The answer, of course, is that it wouldn’t be. By suggesting a way for Dems to get a second bite at the apple, Wittes is proposing to undermine the justice system’s independence.

Indeed, second-guessing Barr by delving into his “work product” goes much farther along the road of “delegitimizing broader internal executive checks on the presidency” than political rhetoric, be it Trump’s or Pelosi’s. This theory apparently requires retraction of Wittes’s previous stance, and others’, that the Mueller report contained the evidential prerequisites for obstruction.

Although the possibility of this strategy getting legs is far off, its formulation is revealing. It has the potential to open another avenue of endless quasi-legal dispute over Trump’s legitimacy. True, such dispute would be applied retroactively to Trump’s presidency. But the threat of delayed judgment is something Dems can keep in their hip pocket. It is, in effect, a new brand of “insurance policy”.

Saving Robert Mueller

Wittes’s analysis illustrates the bind that the left is in. Dems and their media mouthpieces are walking a tightrope. To launch future sorties against Trump, they have to protect Mueller’s reputation for integrity in the face of mounting evidence of investigative irregularities, prosecutorial abuse, and factual distortions. At the same time, they must navigate the political mess the report has left them in.

Presumably this is why we see a trend among leftist national-security-oriented legal commentators to double down on their idealization of Mueller. David Pries, for example, chief operating officer of the Lawfare Institute and former CIA officer under George W. Bush, advanced a novel interpretation for Mueller’s failure to issue explanations for either prosecution or declination in Volume II, as required by the regulations.

Pries asserts Mueller’s non-performance stemmed from uber-valor. Claiming that Mueller reached his conclusions in “strict adherence” to the Office of Legal Counsel’s precedents interpreting obstruction statutes—a claim disputed by other legal experts—Pries also turns Mueller’s losing brief into proof of heroism. Prefiguring Wittes, he says of Mueller: “He self-consciously wanted to preserve evidence for future prosecutors (should they choose to charge the president with crimes after he leaves office) . . . “

Another example is Bob Bauer. White House counsel under President Obama and former partner at Perkins Coie, the Seattle law firm that funneled money to GPS Fusion for the Steele Dossier, Bauer waxes similarly panegyrical.

He attempts to restore Mueller’s plunging reputation by suggesting Mueller is a martyr, a victim of his own unbending integrity in a fallen Trumpian world: “Mueller was under pressure to . . . vindicate regular order when the president and key associates at the center of his inquiry hold regular order in contempt.”

In the end, Bauer laments, Mueller was given too few choices (meaning he had to follow the law) so instead opted to “push the boundaries” (meaning “abdicate his core responsibility”). Bauer refers to “suspended judgments” against Trump, also implying the threat of a second, partisan adjudication.

Finally, there is Goldsmith. He is in a surprisingly small minority among this group of interlocutors in seeming capable of admitting Mueller’s credibility was hobbled long before he failed to pull the ace out of the hole progressives staked their political future on. Although he supports impeachment, he also recognizes that the intelligence community’s “missteps” need fixing and supports Barr’s investigation, albeit with reservations.

He equivocates on the origins of the probe: “I firmly believe that the intelligence community would have been grossly irresponsible had it not pursued this course.” A strange statement, given that it is the factual basis of the justification for the counterintelligence investigation that is now being questioned and that may have provided the rationale for the “[p]olitical use of intelligence” that Goldsmith deplores and Mueller ignored.

Mueller Boosters Haven’t Given Up the Ghost

Whatever comes out in Connecticut U.S. Attorney John Durham’s report, it is clear the mentality of saving American democracy from Trump will continue to thrive. We can look forward to progressive commentators continuing to patch over the intelligence community’s “missteps” by elaborating new theories like Wittes’s latest one that excuse Democrats alone from observing important norms and traditions.

Meanwhile, it will be interesting to see in the coming months if this particular theory succeeds in worming its way into the national discourse.