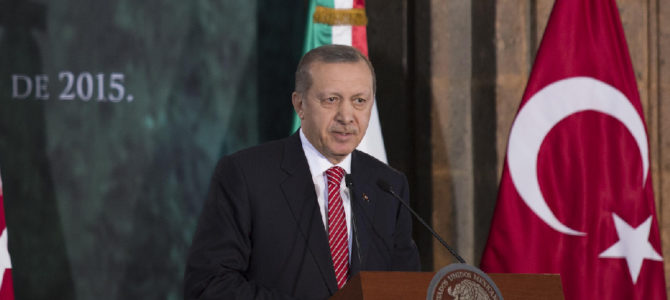

Today most major American newspapers seem to be engaged in a full-court press to do what the plotters of Turkey’s failed military coup were unable to accomplish in July 2016. Turkish opposition leaders, including Fethullah Gülen (the exiled Turkish leader who was blamed for inspiring last year’s coup), are now given free rein to regularly publish editorials in the U.S. press, where they denounce Turkey’s current president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, for his crackdown on political dissent.

One major editorial board recently opined that Secretary of State Rex Tillerson “betrayed democratic ideals” by not criticizing Ankara’s alleged authoritarianism. But Tillerson did the right thing: U.S. government policies should focus on promoting citizens’ security and rights at home, not human rights abroad

For the moment, Erdogan is too powerful and popular a politician in Turkey to be unseated from within or reformed from without. Under his reign the Turkish economy grew on average by 4.5 percent annually, and in 2017 this figure has accelerated to 5 percent. Meanwhile, religious Turks support his policies that expanded the space for religious tolerance in politics, the military, and civil service.

The journalistic assault in the American press to dislodge Erdogan from power is thus unfortunate for Turkish citizens themselves. Such editorials only reinforce his paranoia that last year’s coup was linked to Washington and lead him to fire or jail perceived political opponents.

It is also likely the anti-Erdogan assault in the Western press prominently figures in Erdogan’s daily calculus about whether to further shift Turkey’s strategic direction to the east. In 2016 Erdogan officially apologized to Russia’s President Vladimir Putin for the Turkish military downing of a Russian military plane in 2015, more than half a year after the fact, as if he had finally concluded that he can no longer count on Washington’s support. This year both countries joined a pipeline that will provide Turkey with hundreds of billions of cubic feet of Russian gas annually, and last week Ankara agreed to acquire a $2.5 billion missile defense system from Russia. Turkey’s increasing dependence on Moscow for energy and military equipment threaten its continued participation in NATO and the future of the Incirlik air base, which hosts 1,500 American military personnel.

These developments are worrying because today Turkey’s geostrategic location makes it more important for U.S. foreign policy than at any point since the end of the Cold War. The country borders Iraq and Syria, where thousands of American service members are countering ISIS. It shares a border with Iran, which remains the world’s biggest exporter of terrorism and whose clerical leadership is still bent on developing a nuclear weapons capability.

On its northeast is Georgia, where Russian troops are grabbing new land a decade after illegally invading and occupying South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Its northern coast is directly across from Crimea, which Russia forcibly annexed in 2014; to get access to the Black Sea all naval warships must first get Turkey’s permission. With a few exceptions, Turkey is at the epicenter of U.S. foreign policy. And, according to the latest military figures, Turkey has more ground troops, main battle tanks, artillery pieces, combat aircraft, and attack submarines than does any other NATO ally.

Ultimately, it is in Washington’s interest to have Ankara on its side if a major crisis ever breaks out in Europe or the Middle East. Secularism and liberalism—two key tenets on which the country’s founder, Kemal Ataturk, built modern-day Turkey—will gradually be restored of their own accord.

For the moment, Washington must become more attuned to Turkish strategic concerns, more willing to provide the military aid Ankara requests, and seek to strengthen Turkey’s role in NATO. Americans and Turks will both benefit more from a relationship built on closer military, diplomatic, intelligence, and trade ties than from counterproductive lectures on human rights.