Over the past year, I taught four sections of a course entitled “Understanding Pain” (two sections per semester). Our understanding of pain is a continuous conversation likely to outlast me and future generations.

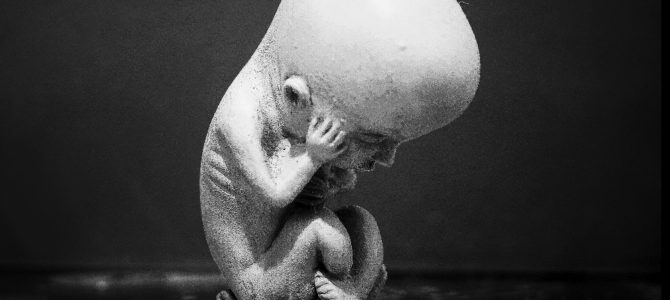

Pain is thought to encompass a biological, psychological, and social tripartite, that greatly depends on all three elements. In light of these three, I cannot argue from a scientific standpoint that a fetus can feel pain, nor do most medical professionals. Scientific studies have revealed specific nociceptive pathways in the body, in which nervous system pain receptors activated by noxious stimuli alert an individual to tissue damage or potential tissue damage. But emotions are also an indispensable part of the pain conversation, which tends to preclude knowing for certain a fetus can feel pain.

Because we have yet to understand all the brain regions involved in processing painful stimuli, it is difficult to definitively answer whether a fetus feels pain. Based on our knowledge of nociceptive pathways, the medical community currently believes pain perception is unlikely before the third trimester or pregnancy weeks 29-30, although the rudiments of nociception are in existence by weeks 7-8 and responsive in the spinal cord by at least weeks 16-20.

This article is not intended to argue the legality of abortion, as I am a scientist. Science is a poor tool for arguing the legality or morality of something. Science is a tool to inform decisions. For instance, science has found that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids can reduce pain perception, although not always. A physician uses this information to determine if certain medications would be appropriate for a patient’s pain.

Science can be used to build a nuclear weapon, but it cannot tell you when to use it. That is, science does not kill people; science provides the knowledge that allows one to kill people. But it also provides the knowledge to help and restore people, which is why I became a scientist.

Let’s Start by Defining Pain

You may have heard the standard definition of pain, as provided by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP): “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.” However, there is more to pain than just that. As the IASP notes:

The inability to communicate verbally does not negate the possibility that an individual is experiencing pain and is in need of appropriate pain-relieving treatment. Pain is always subjective. Each individual learns the application of the word through experiences related to injury in early life. Biologists recognize that those stimuli which cause pain are liable to damage tissue. Accordingly, pain is that experience we associate with actual or potential tissue damage. It is unquestionably a sensation in a part or parts of the body, but it is also always unpleasant and therefore also an emotional experience. Experiences which resemble pain but are not unpleasant, e.g., pricking, should not be called pain. Unpleasant abnormal experiences (dysesthesias) may also be pain but are not necessarily so because, subjectively, they may not have the usual sensory qualities of pain. Many people report pain in the absence of tissue damage or any likely pathophysiological cause; usually this happens for psychological reasons. There is usually no way to distinguish their experience from that due to tissue damage if we take the subjective report. If they regard their experience as pain, and if they report it in the same ways as pain caused by tissue damage, it should be accepted as pain. This definition avoids tying pain to the stimulus. Activity induced in the nociceptor and nociceptive pathways by a noxious stimulus is not pain, which is always a psychological state, even though we may well appreciate that pain most often has a proximate physical cause.

An important part of this definition is that verbal communication is not necessary to convey pain. That is why one might argue that animals feel pain, as we can observe an animal’s behavior after it has been wounded, which informs us to treat or euthanize the animal. It may surprise you to know that animals cannot feel pain—or, at least, the scientific evidence for that does not exist. Animals may very well experience a nociceptive response due to a noxious stimulus because we can directly measure that through electrophysiology and other means, but the experience of pain in animals is something humans attribute to them.

It is not entirely possible to objectively measure pain, but we can directly measure the activation of the neurons responsible for conveying nociceptive information to the central nervous system. We perceive pain at some point in the brain, which is wholly different from its sensation. Any optical illusion can impress upon you the difference between sensation and perception.

Just because a fetus cannot verbally communicate pain, then, does not negate the possibility that it can feel pain. So, as with an animal, we have to rely on behavior to inform our decisions. While we will likely never know whether an animal feels pain, a veterinarian should not withhold medication, just as a doctor should not.

Further, scientific researchers are careful to note changes in animals’ behaviors and decide whether they should be sacrificed to eliminate distress. This is what one would have to focus on to ascribe pain to a fetus. It is also why we would still treat an elderly patient with Alzheimer’s or an autistic child who cannot appropriately communicate his or her pain.

Pain Is Subjective and Internal

Second, this definition tells us that pain is subjective, and can only be understood by the individual who experiences it. Many physicians will discount patients’ pain because it cannot be observed directly. Some compare pain to the color of an object, which is a misunderstanding. Color is something more than one person can perceive, as it is external to the body. Yes, people will differ in their description of colors, especially if they have mutations in the proteins responsible for transmitting sensations that we associate with specific colors, but it is nonetheless a shared perception. Pain is not.

Certainly, a patient can lie, say he is in pain, and acquire opioid medication. But that does not mean we can refuse treatment. Doctors are recommended to not withhold medication on the assumption that a patient is lying. We would rather treat a lying patient than withhold treatment from a patient with actual pain.

Following this logic, we cannot objectively say that a fetus cannot feel pain, just like we cannot objectively say that an animal does not feel pain. Instead, we must rely on biology and make assumptions. Otherwise, we have to accept that even the grass we cut might feel pain, if we ignore the biology as we currently understand it. However, plants’ underlying biology does not appear to permit such a sensation, discounting beliefs in their ability to perceive pain. This is why the lack of specific neuroanatomical circuits suggest a fetus cannot feel pain before the third trimester.

People Can Feel Pain Without Receptors Or Consciousness

The argument that a fetus is likely not to perceive pain before this time is based on the fact that the thalamocortical connections that would permit this perception are not fully developed, especially since these circuits are responsible for consciousness. However, it can be argued that these connections are not necessary to perceive pain, even though they might be necessary for consciousness. It has been known for some time that a doctor can lesion these thalamocortical connections yet pain can persist in the patient. Patients can even develop a central pain syndrome, which may include loss of cutaneous pain sensitivity but pain perception continues nonetheless (Wall and Melzack, “Textbook of Pain” 2013, p. 182-197).

Further, patients under general anesthesia, which is thought to eliminate all consciousness, have reported feeling pain during surgery, which has led to legal action. Again, since pain depends on self-report, one cannot discount this perception. If either lesion of thalamocortical projections or loss of consciousness does not eliminate pain, why do we assume they are necessary features for pain perception?

Similar results about a lack of pain reduction or the development of a central pain syndrome have been reported in many of the areas of the brain and spinal cord known to mediate nociceptive responses (Wall and Melzack, ibid.). In fact, lesion to the somatosensory cortex, which is the final destination of nociceptive signals, as presented in most anatomy textbooks, rarely produces a loss of pain perception.

In essence, eliminating nociceptive pathways is not sufficient to completely eliminate the perception of pain, even in areas we think are responsible for human consciousness. The suggestion that higher-order central nervous system processing areas are necessary for all pain perception is a simplification. In all likelihood, pain is more similar to long-term memories, where coordinated activity in multiple brain regions may be necessary. In this case, fetal pain would be even less likely as these structures and connections would not exist at their point in existence.

These Structures Aren’t Fully Developed Until Age 25

This explanation has its downsides. The idea of a pain matrix, using cognitive neuroscience techniques, has more recently been found to fail at its goal of correlating brain function with pain expression. Even the excessive elimination of limbic structures in patients fails to eliminate pain perception. Taking the argument of the pain matrix at face value, however, presents a conundrum for using higher order processing as a sole basis for pain perception. One important region thought also to be involved in pain, the prefrontal cortex, is not fully developed until age 25 (Wall and Melzack, p. 111-128). Following this logic, we might conclude that anyone under 25 cannot feel pain, or at least, not in the same way as someone who is 30.

These studies have led many to argue that pain has an emotional and cognitive component, the most important aspect of pain based on the IASP definition. However, emotion is a learned phenomenon, just as pain is. Many accept that emotions express physiological responses conditioned, or learned, from our parents and culture, which contribute to the social aspects of pain. In fact, nineteenth and early twentieth century research suggested that those who were considered inferior or criminal felt less pain. The idea that “lower cultures” in uncivilized nations had higher pain thresholds or tolerance suggested they were morally inferior.

Instead, Europeans believed they suffered pain to a greater degree because they were morally superior. Further, some argued that domesticated animals suffered greater pain because of their proximity to humans. It was thought that enlightenment determined how much pain one would experience. In late nineteenth-century Canada, some argued middle-class women had “evolved” to be more sensitive to pain. If interested in the historical perspective of pain and emotion, you can read about it in this book.

Currently, some argue that women, minorities, or those of lower socioeconomic status are inferior because they have lower pain thresholds and tolerance, the exact opposite as before. Therefore, a clear cultural component leads to contradictory positions on this topic. Hence, those who argue the emotional or even cognitive role in pain will tend to use it as a measure of superiority or inferiority, which is not appropriate.

What we understand is that emotions and cognitions influence the perception of pain and occur simultaneously with pain processing. It is the simultaneous occurrence of emotions and cognitions that follow self-report of pain that leads to the conclusion that pain is always psychological. It is easy to explain this principle since we use weapons or wounds as metaphors to express emotional pain, as in the case of the broken heart. Biologically, one’s heart is not broken, but the expression is nevertheless an accurate descriptor for the individual.

We Learn to Associate Pain with Certain Physical Changes

Further delving into the definition, note:

Biologists recognize that those stimuli which cause pain are liable to damage tissue. Accordingly, pain is that experience we associate with actual or potential tissue damage. It is unquestionably a sensation in a part or parts of the body, but it is also always unpleasant and therefore also an emotional experience… Activity induced in the nociceptor and nociceptive pathways by a noxious stimulus is not pain, which is always a psychological state, even though we may well appreciate that pain most often has a proximate physical cause.

Again, the emotional component is something that is learned along with pain, but we have to recognize that both likely stem from some initial biological process that involves nociception. This is an eliminative materialist stance, which is why the phrase psychological state is used, which at some point we accept must have some biological presupposition.

Why do I accept this line of reasoning? There is a rare condition known as congenital insensitivity to pain. People with this condition lack the appropriate nociceptive aspect of pain and therefore do not associate what we might consider painful sensation, which are conveyed by these signals, with the emotional and cognitive aspects that are thought to be requisite for the perception of pain. Because of the lack of this sensation, those who have the condition must learn to associate another sensation with the appropriate response, for example “ouch.”

But this person is not saying “ouch” because he feels pain, but because he has learned that this response leads to treatment for potential tissue damage. They are conscious individuals, but they do not feel pain. The converse is also true, that someone might not have any apparent tissue damage, but express that he or she is in pain. This fact is what prevents us from only ascribing pain to nociception, but I think the emotional aspect is the brain attempting to explain an occurrence and attributing it to what has been perceived as pain in the past.

This is much like how our brain fills in gaps and allows for optical illusions in order to make sense of reality as the individual understands it. Again, this does not mean we do not attempt to treat the pain, as it is nonetheless a real phenomenon for the patient.

This has been recognized abundantly in patients who feel pain in a limb that no longer exists. Here we have a conscious individual who experiences a pain that biologically should not be there. One explanation for this apparent paradox is the infiltration of nerve signals into those areas of the brain that were once responsive to the missing limb (Wall and Melzack, p. 182-197). There have been some successful reports of mirror therapy to reduce phantom limb pain.

Here, the patient is treated by displaying his still-functioning limb in a mirror, giving the perception of having both arms. As patients move the normal arm, they can see similar movements of an arm that is very much like their lost arm. Referring to pain as always a psychological state, again, is more of a filler based on eliminative materialism. A psychological state has some biological component that we do not quite understand, but a patient in pain will usually refer to an emotional and cognitive response that has at some point been associated with nociception in early life.

In Short, Pain Is Both Physical and Mental

So it is likely, in early human development, that nociception is necessary to form the concept of pain. It might be that pain, in early life, is conveyed primarily through the canonical nociceptive pathway, but later it is conveyed by many different brain regions that we have yet to fully identify, that are also responsible for the emotional and cognitive aspects of pain that always exist contiguous with what a patient refers to as pain, whether there is nociceptive signals or not. This may explain why lesion of the nociceptive pathway is not sufficient to eliminate pain.

However, if one lacks this nociceptive input throughout development, he or she fails to develop pain perception. It is well understood that our perception of the world depends on associating sensations within environmental contexts, such as learning that the word “ouch” should follow activation of nociceptors due to actual or potential tissue damage. Along with this, the idea of critical periods is also well-established and is likely true for pain.

Since we know that nociception exists at the level of the spinal cord, at least by gestational weeks 16-20, it is likely that this may begin the process of learning what pain is. However, the perception of pain is learned via a multitude of life experiences, making it difficult to put an exact developmental period at which this perception is learned. It is quite possible that fully developed pain perception does not exist in humans until age 26.

However, we are not apt to say that those under 25 cannot feel pain, even though we really do not know exactly when pain becomes a salient feature of one’s life, if it ever does. To argue that fetal pain does not exist prior to the third trimester is to argue that our understanding of pain is complete and to ignore the overwhelming evidence that it is not.