Vladimir Putin has suddenly emerged onto the world stage as a conservative. The former KGB colonel, turned democrat, turned technocrat styles himself a modern Tsar in the mold of Nicholas I. Indeed, the official ideology of that especially conservative despot, “orthodoxy, autocracy and nationality,” resonates eerily with Putinism’s most recent mutation. The Russian President has good reason to believe that a stronger sense of national identity, coupled with a more religious and family oriented culture would benefit his country. His choice of timing, however, suggests political expedience, as well as a profoundly shrewd geostrategic insight.

Russia’s rightward turn renders Putin’s regime immune to the criticism of western liberals, and polarizes western conservatives. It therefore strains the Atlantic alliance, and neutralizes the claims of policymakers in both Europe and the United States that Russia’s resurgence presents a threat. Thus it strengthens Putin’s hand in the former Soviet periphery, Eastern Europe and in the Middle East against the moral, legal and political objections of Western governments. Moreover, it establishes an entirely new ideological precedent for autocratic regimes who seek to challenge the American led world order. As Ukraine’s liberals seize the initiative against a government that enjoys Putin’s backing, they will look to the Western world for validation and support. The West could easily respond in kind; as of late however, its leaders have either been too reluctant, or have forgotten how. If Western Europe and the United States are serious about sustaining a world order that prevents conflict, enables prosperity and promotes liberty and the rule of law, then their governments should defend it on those terms. Evidently, the Kremlin has figured out how to either shut them up or turn them against each other.

Putin is undoubtedly looking for a new organizing principle for his regime. For the past decade he has given Russia a restoration of political order, and a rising standard of living courtesy of steadily rising oil prices and an increasing European dependence on Russian natural gas. The protests that rocked Moscow in 2011 and 2012, however, served as the proverbial writing on the wall: Putin can no longer reliably depend on a rising standard of living in Russia to secure his people’s affection. Moreover, in the long term the emergence of the United States as a natural gas exporter likely spells the end of Gazprom’s role as the guarantor of Russia’s internal stability. As the standard of living among Russia’s Middle class withers, resentment of the Kremlin elites’ corruption, wealth and autocracy will inevitably boil. Putin’s sudden turn to matters of national identity, the Russian soul and the Russian family suggests that he is effectively adopting a compensatory ideology that can sustain his rule.

Putin’s embrace of social conservatism does more than promote Russian religiosity or “traditional values” domestically; however, it targets and exploits latent Western frustration with post-modern liberalism itself. In his most recent address to the Russian Federal Assembly, Putin spoke disdainfully of what for decades Americans have known as “political correctness”:

Today, many nations are revising their moral values and ethical norms, eroding ethnic traditions and differences between peoples and cultures. Society is now required not only to recognize everyone’s right to the freedom of consciousness, political views and privacy, but also to accept without question the equality of good and evil, strange as it seems, concepts that are opposite in meaning. This destruction of traditional values from above not only leads to negative consequences for society, but is also essentially anti-democratic, since it is carried out on the basis of abstract, speculative ideas, contrary to the will of the majority, which does not accept the changes occurring or the proposed revision of values.

To hear a former KGB colonel bemoan the “erosion of ethnic traditions and differences between peoples and cultures,” and the “destruction of traditional values from above” is at the very least amusing, if not astoundingly mendacious. Putin is nevertheless speaking to sentiments that an increasing number of Westerners share. Moreover, he is the only statesman of any noteworthy stature who is publically addressing them.

In the United States, Putin’s right turn has exacerbated old divisions among its conservative intelligentsia. The reaction of some conservatives to Putin’s December speech has been positive, if not affirming. Putin’s call to return to traditional values and scorn for elites who willfully promote “abortion on demand, homosexual marriage, pornography, promiscuity, and the whole panoply of Hollywood values” compelled Pat Buchanan to wonder aloud whether Putin “was one of us?” Writing in The American Conservative, William Lind went so far as to claim that “American conservatives should welcome the resurgence of a conservative Russia.” Such praise for Putin couldn’t more strongly contrast the loathing of other American conservatives. Writing for National Review, the Stanford classicist Victor Davis Hanson compared Putin to Milton’s Satan, arguing that “he winds up existing to warn us in the West of what we are not.” Throughout the Cold War, American conservatives were predictably unified in their ideological stand against communism. Indeed, the Soviets faced few enemies as unyielding as those who shared the views of either Mr. Lind or Mr. Hanson. Evidently, Putin has divined the formula for polarizing his more traditional opponents.

Putin’s appeal to right in Europe is far more serious. In his speech to the Duma in June of last year French rightwing geostrategist Aymeric Chauprade claimed to address Russia “as a French Patriot” who sees “Russia as a historical ally.” He decried the color revolutions, the legalization of gay marriage in his home country, the Ukrainian feminist group FEMEN, and the willful sacrilege of pussy riot. He characterized these unwelcome developments as the result of “the alliance of Western globalism with anarchist nihilism” which persist courtesy of American financial and military might. In what undoubtedly flattered the Kremlin’s elite, Chauprade concluded with the bold declaration that the world’s true patriots “now turn their attention to Moscow.” For most Americans it is likely tempting to dismiss Chauprade as a crank: a representative of a loud fringe element that lacks any real political influence. Recent polling data, projections for the EU elections this May, and the Hungarian government’s recent solicitation of a 14 billion dollar loan from Moscow, however, suggest that Putin’s right turn coincides with widespread European disenchantment with the EU. Indeed, European trust in the government in Brussels is at an all time low. Moreover, as the British academic Matthew Goodwin pointed out, the stubborn persistence of the Eurozone crisis will likely yield many voters who will go to the polls to vent their frustrations.1

Russia’s growing influence in European affairs begs the question, how can policymakers in Brussels counter Putin’s charms? More specifically, how can they address the grievances that many Europeans have against the EU, and indeed the transatlantic alliance itself? The dispiriting answer increasingly appears to be that they cannot; the only electoral trump card that the EU bureaucrats can play against Euroskeptics and the European radical right is the promise of continued economic growth, and the survival of Europe’s generous social programs. Other essential elements of the human condition: religious faith, national identity and a spiritual sense of purpose have no place in their discourse, or indeed in the EU’s very reason for existing. Putin has shrewdly chosen a debate over hearts and minds with an opponent who is entirely ill equipped to respond.

This is not to say that Western liberals and other defenders of the EU cannot go on the offensive, and call Putin out for his blatant moral shortcomings. Surely policymakers in Washington and Brussels can draw attention to the cruelty with which his regime treats the LGBT community, the brutality with which Russia has denied Chechen independence, and Russia’s continued shipment of armaments to a dictator who recently used chemical weapons against his own people. Unfortunately, however, it appears that the Kremlin has already thought these issues through.

On the matter of gay rights, Putin is likely more than happy to draw a stark contrast with President Obama. The choice to select gay athletes to participate in the Olympic Ceremony in Sochi undoubtedly won Obama praise from his supporters at home. On the world stage, however, it stands to reason that Putin was using the very same old Marxist tactic of “heightening the contradictions” against Obama. The choice to send gay athletes in a clear statement of protest against Russia’s “anti gay propaganda” law feeds right into Putin’s claims that global western “elites” are forcibly imposing their “abstract, speculative ideas, contrary to the will of the majority” appear credible. Such is also case with Chauprade’s claims that the United States is a decadent and nihilistic power that is willfully eroding most people’s sense of identity and common decency through its financial and military hegemony.

In the case of Russian skullduggery in the North Caucuses, Ukraine and in Syria, Putin has already won the debate against his Western liberal opponents. Such was evident in the Russian President’s letter to the American People urging them not to intervene in Syria in the New York Times on September 11th last year. Rather than draw a contrast with Obama, Putin cynically harnessed the American President’s very own liberal idealism, internationalism, and scorn for his predecessor’s bold use of American power. Putin warned the American people that action in Syria would undermine the credibility of the United Nations, that it would inspire hatred among foreigners towards the United States for its presumption and arrogance, and that it would prove every bit as fruitless as our efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Russian President’s sophistry notwithstanding, it was a flawless implementation of Saul Alinsky’s fourth rule of political warfare: make the enemy live up to his own book of rules. Many American liberals regarded the audacity of Putin to appeal their sensibilities with indignation, but they were speechless all the same. Senator Menendez of New Jersey claimed that Putin’s piece “made him want to vomit.” The New Republic made the effort to scrutinize it line by line to expose the Russian President’s hypocrisy. When all was said and done, however, none could actually claim that what Putin said was wrong. Thus Putin left Obama with an ugly choice between publically buying his nonsense, or compromising his principles. Obama opted for a third option: make no choice at all.

For an American President who ostensibly represents idealism and progress, Russia’s shirtless, botoxed and gay bashing tyrant should be an easy target of denunciation. Obama and his modern liberal cousins in Brussels, however, remain tongue tied in the face of such a blatant challenge to the world order they represent. Putin has the uncanny ability to simultaneously appeal to their enemies on the right, and beat their supporters on the left at their own rhetorical game. He is both the scourge of Western nihilistic decadence, and a messenger of Kantian perpetual peace in the pages of New York Times. Most disturbing of all, Putin’s successes demonstrate that he intuitively grasps the weaknesses inherent in modern liberalism itself. His objections to its shallowness, decadence, and materialism are especially potent, because they contain elements of truth. He sees that the European Union has a very tenuous hold on the identity of its citizens, and has noted that America’s leaders have articulated little to no vision of their country’s moral purpose in the world. Consequently, Brussels and Washington have effectively allowed their enemies to hold court on humanity’s great questions in international affairs. For the Kremlin, this has proven to be a tremendous reservoir of power that the West has sacrificed for free.

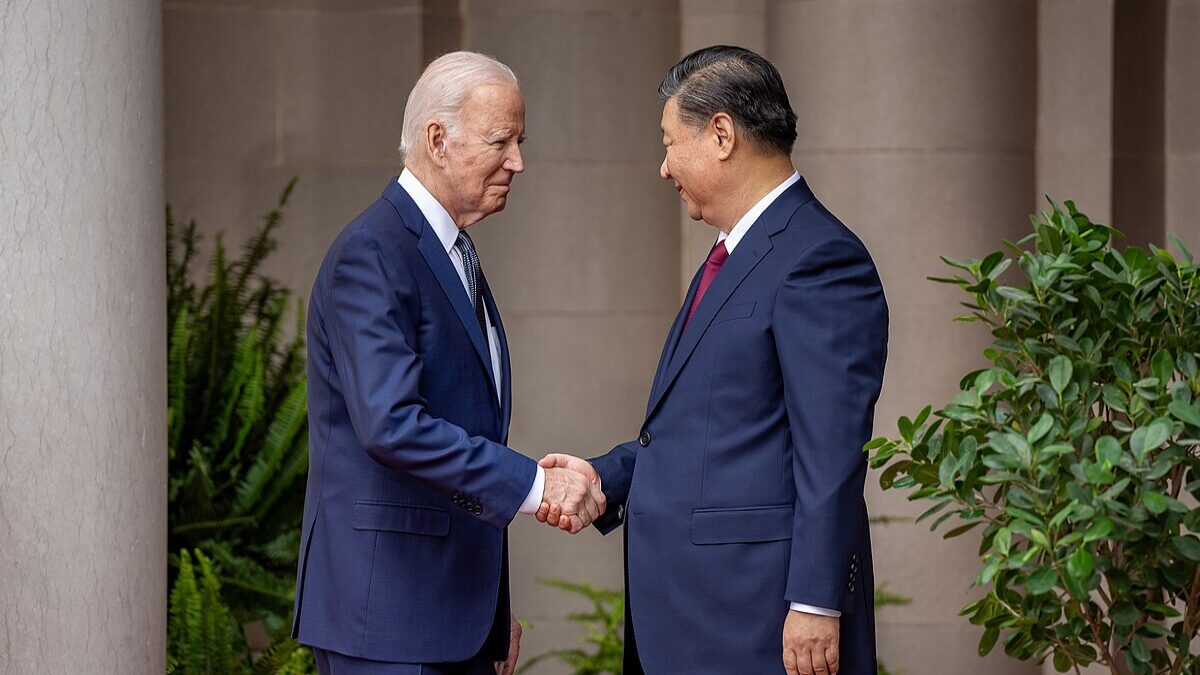

Contrary to the claims of some American conservatives, however, the old Transatlantic Alliance should not welcome Russian resurgence under Putin. True, the new Russia is not the Soviet Union, and it shouldn’t be treated as such. Nevertheless, an empowered Kremlin will only contribute to the withering of the world order that the Atlantic Alliance forged during the Cold War. Western enthusiasts for Russia’s resurgence who believe Putin to be a force of sensible stability would be wise to consider the Kremlin’s willful enabling of Iran’s nuclear weapons program, its armed support for militant Shi’ism, its support for militant leftists in Latin America and its poisonous influence in the Middle East. True Burkean conservative or not, Putin’s Russia is expanding in influence in the same manner as its predecessors: by fostering conflict both abroad and along its periphery. Any attempt by the West to establish an arrangement with Moscow in which both sides respect each other’s “sphere of influence” that relies on Russian contentment within its own borders will certainly fail, just it always has at every other time in recorded history. Moreover, Putin is setting a precedent in the post Cold War era: a great power is challenging Western hegemony on ideological terms. As China’s elite wrestles with the contradictions of autocracy and liberalism, Putin’s turn to conservatism could provide an alternative worth imitating, especially if it proves effective in blunting American power.

Effective grand strategies are distinguished insofar as they are able to articulate their objectives in moral terms, and then methodically filter them through rigorous assessments of what is possible. Currently, Putin is adopting a moral purpose for his country in international affairs, and it is lending him strategic clarity. Western Europe and the United States, by contrast, are increasingly confused about their moral purpose, and have thus lost the initiative in shaping global events. Their statesmen would be wise to blunt the divisive effects of Putin’s right turn by turning back to the basic elements of their civilization, and articulating why they are a force for good. As Ukrainian liberals struggle to gain political traction following their ouster of a Kremlin backed stooge, Washington and Brussels could challenge Russian influence by calling for self- government, ordered liberty and the rule of law. Moreover, they could call out the Kremlin for its lawlessness and aggression. The Kremlin will inevitably shoot back mocking and sophistic charges of hypocrisy: they can be ignored. Putin’s challenge to the current world order lends him power because no one is willing to defend it on its own terms. Thus, the longer Western uncertainty persists, the more its autocratic enemies will gain in power, influence, and strategic initiative.

David Ernst, a graduate student at the Institute of World Politics, is a Research Assistant at the Hudson Institute’s Center for Islam, Democracy, and the Future of the Muslim World.