Five years ago, “Saturday Night Live” ran a sketch in which Will Forte expressed his undying love for college football’s Bowl Championship Series with a comic song. The point was, needless to say, not terribly subtle.

I love stepping in dog crap

And I love it when children get sick

I love paper cuts on my corneas

And I love the BCS

I love hanging at the DMV

And I love finding out I’m adopted

I love eating tacos filled with uncooked chicken

And I love the BCS

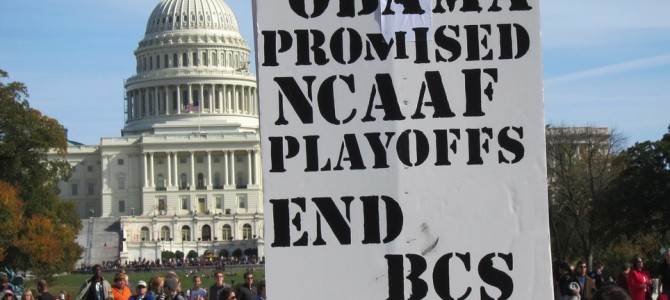

The week after it aired, about half-a-dozen friends sent me the link. I guess I was the only sado-masochist any of them knew who was willing to defend the BCS. That may help to explain why the BCS is now ending, to be replaced in January 2015 with a four-team playoff.

We’re not going to hear a lot of weeping over an arrangement that everyone loves to hate. I personally agree with University of Alabama head coach Nick Saban, however, who remarked, “When we look back at it, we’re going to see that it probably wasn’t all that bad.” Actually, I’m a little more pessimistic than Saban. I fear that we may look back on the BCS years as a golden age for college football. We may find, twenty years from now, that we all retrospectively love the BCS.

The Injustice Complaint

I realize that half of my readers are already in the barn hunting for their pitchforks. For those that remain, however, let me start by acknowledging the ugly. The BCS ranks college football programs using a computer algorithm that factors in, among other things, team record, strength of schedule, and the cumulative opinions of a committee of human beings, some of whom most likely have not watched more than a handful of the teams they are ranking. Unsurprisingly, almost nobody is satisfied with the results, and fans can sit for hours arguing about which of the many injustices of the BCS era wins the prize for being most egregious. Undefeated Auburn’s exclusion from the 2004 National Championship? The 2011 Alabama team that got the nod over one-loss conference champ Oklahoma State, even after failing to win its own division? Or perhaps you have a special soft spot for “BCS busters” like the 2008 Utes, who beat mighty Alabama and ended the season as the nation’s only undefeated team, but never got to play for the National Championship. (New evidence does suggest, of course, that the Crimson Tide only perform well in the post season so long as they’re playing for the National Championship. If there’s no crystal football in the offing, they just phone it in. Perhaps Utah’s victory was less impressive than we once supposed.)

Beyond the individual injustices, there is the principle of the thing. The BCS offended the sensibilities of sports fans, who have a deep yearning for performance-based meritocracy. Sports is satisfying to us in large part because it enables us to construct an artificial justice, such as is rarely found in other areas of life. You don’t win glory by being good-looking or charming, and even athletic talent is worthless except to those who can develop it through discipline and hard work. Glory comes to those who can do it on the field. This basic foundation of fairness is critical to the drama of sports. Both the elated highs and the soul-crushing defeats draw their strength from the realization that the glory or shame were earned; they reflect the greatness or weakness of the athletes and coaches, not the whimsical vicissitudes of Lady Luck. This is why sports fans get so enraged by bad referees, performance-enhancing substances or erratic ranking systems. They seem to threaten that core of justice that is so critical to the value of sport.

Of course, the BCS system does try to rank teams fairly, and no crazed fan has ever successfully proven that the system is deliberately rigged. Still, the cryptic and largely subjective nature of BCS rankings does indeed diminish the perfection of the college football meritocracy. Fans hate the way it raises the specter of girly sports like gymnastics, figure skating or synchronized diving, where everything comes down to the opinion of biased judges, and to semi-arbitrary standards that only experts understand. Such flim-flammery is not worthy of a great sport like football.

Football has a thick rule book, and is arguably the most strategically complex sport ever known to man; nevertheless, at the end of the day, even small children can understand that the winner is the team that most successfully gets the ball into the end zone. This juxtaposition of complexity and simplicity is the mark of a great sport. It is always preferable (all else being equal) to hang success on that deliciously simple algorithm, and not on the opinions of rarefied experts.

The Playoff

Now we come to the Christmas present college fans have been begging for almost since the BCS began: a playoff. The plaintive whining has been echoing through sports forums for years now. A playoff would legitimize the sport. We could move past the beauty pageant of BCS voters and finally settle things on the field. A playoff would make things fair.

At last, the NCAA has caved. Like parents who just couldn’t handle one more lecture on how “the puppy will teach me responsibility,” they broke down and gave us our playoff. As of next year, four committee-selected teams will face off in two semi-finals, with the winners to meet in the first college football playoff-selected National Title game.

It sounds great, right? Not so fast. Let me start with the obvious. There are 125 teams in Division I football. Four will compete in the playoff. Those four will be chosen by a committee of 13 humans, who are at liberty to use whatever criteria they see fit in making the selection. Don’t look now, but I think this is still a beauty pageant.

A four-team playoff will frequently leave out teams that could have a legitimate chance of winning it all. The 2008 Utes, for example, most likely would not have been selected. So there will still be endless arguments about the injustices, in which everyone will quickly assume their familiar roles. Teams from the more obscure conferences will contend that record should matter more than strength of schedule, and that it’s not their fault Ohio State and Boston College wouldn’t return their calls. Braggarts from the Southeast Conference will boast that, honestly, none of the other conferences have any respectable teams, so why shouldn’t we have an all-SEC playoff? This could quickly come to look like a movie we’ve all already seen.

As usual, though, the sequel will be less good than the original. With the playoff system established, the rest of the post-season will recede further and further into the background. Under the BCS, the National Title game was a cherry on top of a delicious Bowl Sundae. The BCS post-season has always served up some wonderful games, and in fact, this year’s bowl sequence has been a string of almost non-stop thrillers, as if the stars have somehow aligned to remind us how good we really have it, right before we kill the golden goose. Officially the bowls will still exist next year, but realistically, a playoff has a tendency to suck all the oxygen right out of the room. Every game that doesn’t “go anywhere” might as well be re-named the Also Ran Bowl. We’ve traded a rich bowl tradition for a mess of playoff pottage.

Just Not A Playoff Sport

The specifics of the playoff can be adjusted, and will be. Almost immediately, fans will begin rallying for a larger playoff so that more teams can get into the mix. There will be some inevitable tinkering with the selection process, and the informal guidelines may be hardened or just rewritten. Committee members may be traded in and out as we strive to find the perfect judging panel. In the end, though, we will have to sit down and admit to ourselves that college football simply is not a playoff-friendly sport. If we try too hard to regularize it, we may end up destroying the things that make it wonderful.

To some extent this is just a matter of numbers. To adequately represent 125 teams, the playoff would have to be large. But football is a physically punishing sport, and most everyone recognizes that it would be unreasonable to ask unpaid college athletes to play in a March Madness-size tournament. If we want the playoff selection process to be more fair, we will need to make better use of the regular season by smoothing out some of the inconsistencies, thus making it easier to judge teams based on their regular-season performance. As the quest for meritocracy continues, we are likely to see conferences, recruiting practices and scholarship numbers adjusted in an effort to level the gridiron and make teams more comparable.

We’ll gain something. There will be fewer blowouts and more close, hard-fought games. But consider: if meritocracy is such an all-encompassing good, why do people even bother with college football anymore? Why not focus their energies on the near-perfect meritocratic machine that is the National Football League? The NFL provides us with a supremely high-functioning football machine in which it really does all come down to what happens on the field. If you want an illustration of just how unsentimental a pro franchise really is, try watching an episode of HBO’s “Hard Knocks,” which documents in excruciating detail the struggles of those unfortunate characters who have spent their lives as athletic superstars, and who suddenly find that their best just isn’t good enough anymore. Or, if you don’t have time for that, just consider the amazing fact that fan super-favorite Tim Tebow is not currently on an NFL roster.

NFL rules and procedures have been relentlessly adjusted to bring us what is arguably the highest-functioning athletic organization in history. The level of play is fantastic, and the games are hard-hitting and suspenseful. There is a reason why Forbes’ list of the world’s most valuable sports franchises is dominated by NFL teams. For all its merits, though, there is a soulless, even socialist aura surrounding the NFL. Super Bowl winners are rewarded with rings and the worst picks in the subsequent draft. Your favorite player could be suiting up for your arch-enemy next week if something goes wrong with his contract. Most of the players on your home team probably grew up rooting for someone else, until a multi-million-dollar contract changed their loyalties. It’s hardly even possible anymore for an NFL player to be anything more than a gun for hire.

College football is different. In terms of performance, it will always trail far behind its professional counterpart. Nevertheless, there is a reason why it remains far and away the most popular college sport. College fans will tell you that they love the younger athletes for their heart and their spirit. They play for love of their team, their school and their sport. It’s not about a paycheck. That isn’t only because the college athletes are unpaid and (for the most part) stuck with the team that signed them. It’s because the college football landscape reflects the American cultural landscape in a way that pro football just can’t anymore.

Why are certain conferences and teams consistently stronger than others? Of course money is a factor, but on a deeper level, it reflects the significance football has in a particular region. Kids grow up cheering for their local team, and then the talented ones go on to play for that team. They become the little platoons that represent their people, fighting for the honor of home and family. Or, in a few special cases, they fight for a different kind of honor. The service academies proudly defend the reputation of the US military on the gridiron. Notre Dame carved out its hallowed place in football history by representing Irish Catholics in a Protestant society that despised them.

Conferences and rivalries have grown up across the college football landscape in an organic way that reflects other idiosyncrasies of American culture. Behind every rivalry is a story, or perhaps a book of stories, that reflect something about the school and the athletes and the fans that fueled the competition. Professional teams have rivalries too, but precisely because it hasn’t been ruthlessly regularized, the college game can give a clearer and more meaningful expression to the hopes and aspirations of a particular people.

Must we choose between the goods of meritocracy and the goods of cultural representation? Probably it would be most accurate to say that there are trade-offs. The BCS did a fairly good job of protecting the organic network of programs and rivalries that make up the larger college football tradition. It was less successful at providing a clear and obviously just method of ranking teams. So it didn’t give us everything, but it gave us an awful lot. If we could pull ourselves away from the injustice debate for a moment, we’d realize that there are a lot of great memories from the BCS era of college football.

Thinking about it a bit more, we should realize that football fans are extremely fortunate. We really can have it all. We just can’t have it all in the same system. The NFL offers us the benefits of ruthlessly mechanized sporting meritocracy. College football is messier and more irregular, but it has the beauty intrinsic to an organic sports tradition that can still express the spirit of the American people in a deep and satisfying way. If we edit out those glorious idiosyncrasies in an effort to make the sport more fair, we will end up with an inferior version of something we already had. College football will cease to have a significant identity of its own, and will become more equivalent to a minor league, which is of interest only to truly committed fans.

We all sustained a few bumps and bruises (metaphorically speaking) in the BCS era. At the end of the day, though, wasn’t it a thrilling ride? Is it really so impossible to love the BCS?

Rachel Lu teaches philosophy at the University of St. Thomas.