About once a week, I read another manifesto from someone who is quitting social media. Like resigning politicians, people offer a list of reasons for their Big Decision, which actually are weirdly reminiscent of those a politician might give. They’ve lost sight of what really matters in life. They need to spend more time with their families. The stress isn’t good for their health.

A friend recently suggested to me that all these resignations might portend a decline in the popularity of social media. I’m doubtful. To my mind, the dramatic nature of these announcements suggests exactly the opposite. Ten years ago we had never heard of Twitter, and now living without it is a major lifestyle change, like becoming a vegetarian or giving up television. It would seem that social media have infiltrated pretty deeply into our lives.

Innovations can do that. Every now and then, a new one comes along that substantially changes the course of daily life. Perhaps it fills some deeply-felt need, or unleashes a previously-untapped wellspring of human potential. Either way, truly transformative innovations can quickly change the face of society such that retreat seems impossible. Think about cars, cell phones, television or the internet. In just a few short years, goods like these can morph from novelty items into necessities.

Ironically, it may be the truly remarkable innovations that provoke the most criticism and angst in society at large. Properly understood, this is a tribute to their success. Tickle-me-Elmos and Chia Pets are unlikely to inspire much soul-searching, because they can just be discarded once the novelty wears off. Cars, by contrast, kill more than twenty-five thousand people each year without deterring us from buying more. We lament the risks and the environmental impacts of driving, but at the end of the day, we can’t live without cars. So we find ways to live with them. We build seat belts and install airbags and go on driving.

Social media is an innovation of this kind. We have allowed it to change us, such that there’s no going back. Even the people who resign in style generally find their way back sooner or later. They may switch from Twitter to Facebook, but it’s hard to live without social media nowadays. To understand why this is, we might glance back to Robert Putnam’s turn-of-the-millennium classic, “Bowling Alone.”

Social Capital Impoverishment

“Bowling Alone” popularized the idea that humans need “social capital” in order to be happy and thrive. This is the sort of good that we derive from friendship and family life, and more generally from our participation in human communities. Having loved ones you can trust, Putnam argued, is of tremendous worth. Unfortunately, he found evidence that Americans were becoming seriously impoverished with respect to social capital.

For Putnam, the problem can be neatly illustrated through a look at the fate of American bowling leagues. Bowling has actually become more popular since the sixties, but bowling leagues have gone into serious decline. People still bowl, but they do it alone. Putnam found similar patterns across a wide variety of clubs and civic organizations, leading him to conclude that the United States was turning into a country of antisocial loners who would opt for the flickering of their televisions over the give-and-take of communal activities that might promote discussion and the formation of civic movements. Bowling leagues were once the ultimate grassroots organization, until Americans became too lazy and fragmented to keep them alive. This fragmentation, Putnam believed, explained much about the social decay and general unhappiness that Americans were exhibiting.

“Bowling Alone” was published in 2000, four years before the advent of Facebook and six years before Twitter. Online socialization was already happening, of course, in chat rooms and through more personalized programs like Instant Messenger, but these were fairly crude, and their overall effect on social capital was probably marginal. Putnam saw computers mainly as a social negative. He blamed “the glowing screen” for eroding social capital, since it gave people more reasons to stay home alone instead of going to the Kiwanis Club. In retrospect, however, Putnam looks decidedly non-prescient in his failure to appreciate the potential of online social media. Even as “Bowling Alone” went to press, social media was on the brink of a revolution. In a country full of lonely people, with inadequate social outlets and a surfeit of flickering screens, the time had come. Putnam’s book preceded that social revolution by just a few short years.

Between 2003 and 2006, MySpace, Facebook and Twitter all launched. Other, more targeted social sites such as Linkedin, YouTube and Yelp were started in this same period. The age of social media was upon us. And even though these innovations provoked a chorus of complaints almost from their opening hours, they also attracted users by the millions. The verdict was in: social-capital-impoverished Americans were ready to use their glowing screens to talk to one another. Both Facebook and Twitter now boast hundreds of millions of active users, and the last few years have witnessed the launch of several new social media services such as Google Plus and Pinterest.

As with every major innovation, there are positives and negatives to the change. On the positive side, online socialization has had a definitely positive effect on the generation of social capital. Social media services help us to connect with those who share our interests, while also providing a comfortable medium for bolstering relationships with people we already know. Many of us already have friends and relatives scattered across the country and world, but time and distance have made it difficult to keep in touch with them. Social media enables us to re-kindle those ties.

Re-kindling Old Ties

It is easier to interact with old friends when we can reach them all at once, without the intrusiveness of a ringing phone. Most people appreciate this opportunity for a renewed closeness with loved ones. Instead of opening the paper and getting the morning news with our coffee, we can now open our laptops and get a personalized update on the people we most like. This is a much happier, more affirming way to start a day. Smart phones take things a step further by enabling us to carry our community in our back pockets. We are always in a position to share a cute picture or pithy comment, and to receive feedback in a matter of minutes, from people whose opinions we trust. To a lonely and under-socialized society, these are genuinely wonderful gifts.

Of course there are also problems. Social media cannot replicate every element of face-to-face interaction, and precisely because it does alleviate loneliness and isolation, it may make us even less inclined to rise from our armchairs and head off to the PTA meeting. That might be a bad thing, because there are downsides to having your closest friends scattered across the country. If your ox falls into a ditch, opposite-coast Facebook friends are in no position to help. (On the other hand, if a natural disaster levels your home town, it might be good that your bff lives three hundred miles away.)

Then there is the issue of decreased productivity. Social media services are so convenient that some find it difficult to tear themselves away. As with any addiction, the solution is to develop better self-control, but there will always be people in the world for whom this proves prohibitively difficult. Don’t be surprised to see “Facebook fasts” or “Twitter Anonymous” becoming a regular part of the American landscape.

Perhaps the biggest downside to social media, however, is its tendency to spur humiliation, animosity and boorishness. It brings people together, but does not necessarily encourage them to behave themselves. Teaching mannerly behavior has never been easy of course, and we can at least feel grateful that virtual interaction dis-enables physical violence. Still, the potential for gutter-level verbal exchange seems particularly high in the virtual world. People share things that are excessively personal, and then feel embarrassed or wounded by the response. They get in nasty arguments that rage on for days. Or, just as bad, they post inflammatory opinions and start deleting the remarks of friends who disagree, causing social rifts or intra-family feuds. In short, social media opens whole new vistas for rudeness, and our personal relationships suffer the consequences.

Making Social Media More Sociable

If indeed social media is here to stay, it will be worth our while to minimize the negative impacts. Just as our car-addicted society has devoted considerable energy to creating safer cars, so we must now put some effort into making social media more sociable. In part, this project may involve some continued adjustments to the technology. In the main, though, it will require self-control and prudent adaptations to the rules of etiquette. Social media raises new etiquette challenges, so we may need to work out some new rules to help govern its use.

Three features of social media make it particularly challenging. First, the convenience goads some people into over-sharing. Second, virtual interaction provides relatively few cues as to our interlocutor’s emotional state. We don’t see the facial expressions or hear the vocal inflexions that might persuade us to back off when the conversation heats up. Third, social media services make it difficult to adapt remarks to the audience. Every time you air one of your views on Facebook, you’re opening it up to any combination of friends or relatives who might care to comment; it’s like Thanksgiving dinner awkwardness 365 days a year. Most people don’t have the diplomatic skills to mediate that kind of conflict, so social media exchanges can turn ugly or awkward.

It’s hard to get around the fact that self-control must be exercised by individual selves. Over-sharing is the sort of problem that people may just have to get over through a painful process of trial-and-error. But audience regulation is the sort of difficulty that technology and etiquette might help ease. In some respects it seems unfortunate that social media services have bestowed miniature soap boxes (or bully pulpits) on all of us, just at a time when society that is so deeply polarized by serious political and moral disagreements. But the good news is that navigating disagreement is the sort of skill that can be learned, and it may be that social media’s greatest pitfall also represents its greatest promise. Robert Putnam wanted to see Americans mixing and mingling and sharing ideas. They are doing so. If we can figure out how to live with each other online, perhaps we can learn to do it offline as well.

Tolerance is difficult, and it is essential that we not glaze over the difficulties with happy platitudes about respecting everyone’s entitlement to an opinion. It is a familiar fact by now that people who loudly advertise their commitment to tolerance should generally be approached with caution. They are generally the nastiest of all when real disagreement arises. This is true for the same reason that veteran soldiers rarely boast about their skills in the way that a green recruit might do. Those who know the business understand that it is too serious for bravado. It takes considerable practice and discernment to learn how to handle grave disagreement without alienating friends or compromising our own integrity.

With time, good will, and reasonable expectations, this skill can be learned. And the good news is that social media have almost infinite potential for enabling us to practice, if we can avoid ripping each other’s throats out (metaphorically speaking) while learning the curve. Tactful management of serious disagreement requires us to find careful balance between seeking common ground and drawing lines where common ground does not exist. Etiquette can help by teaching us how to disengage when the potential for progress seems minimal.

Exit Strategies

Perhaps what we need, then, is a range of graceful “exit strategies” that enable people to back out of a discussion when it gets uncomfortably heated. Technology can make this easier by providing convenient ways to “unfollow” a conversation or perhaps just hide (or delete) an entire thread. But the key really lies in both sides’ willingness to respect (at least in that polite-fiction manner that generally suffices for etiquette) that withdrawal from a conversation implies nothing about its content. However angry we are, we cannot demand a rebuttal from our friends, nor should we accuse them of cowardice or oversensitivity if they wish to disengage. On the other hand, withdrawing parties may not claim victory by fiat, nor are they entitled to the last word in the conversation. If you don’t want to talk about it any more, stop talking.

Facebook, because it enables people to edit their own comment threads, is particularly bad in this respect. Airing an opinion in public and deleting people’s replies is deeply insulting. It is as though you had invited friends for a dinner party and held forth on your own opinions, only to silence anyone who tried to offer a contrasting view. (‘Nobody wants to know what you think!”) Friends occasionally point out to me that they might, in fact, evict someone from a dinner party if that person was behaving badly and making others uncomfortable. Deleting comments in the virtual sphere is much the same thing. Here, then, is my suggestion: delete comments only as often as you evict people from your home. If everyone will stick to that rule, I think we’ll probably be fine.

As a child attending progressive public schools, I recall being told a number of harsh things about the ultimate fate of quitters. Age and wisdom have taught me, however, that there are a number of things that should not be attempted except by those who know how to quit. Graduate school. Gambling. Dining at all-you-can eat buffets. In certain areas of life, it is essential to learn how to say, “enough, this is accomplishing nothing good”. If we can learn how to politely withdraw from unproductive arguments, social media might realize its potential for generating social capital, relieving loneliness and stimulating productive, free exchange.

Social media have penetrated our lives because we were yearning to talk to one another, and despite the challenges, most of us still want that. Online etiquette challenges are the sort of problem an advanced society should be able to tackle. So go. Join Facebook. And be nice.

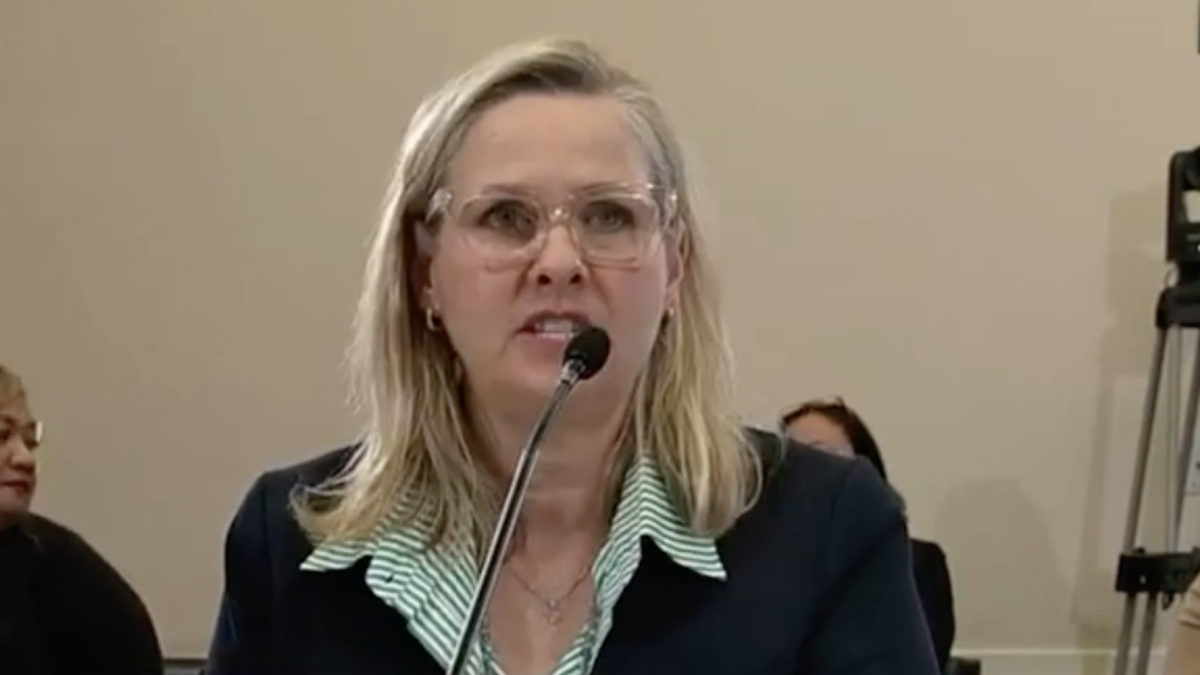

Rachel Lu teaches philosophy at the University of St. Thomas.