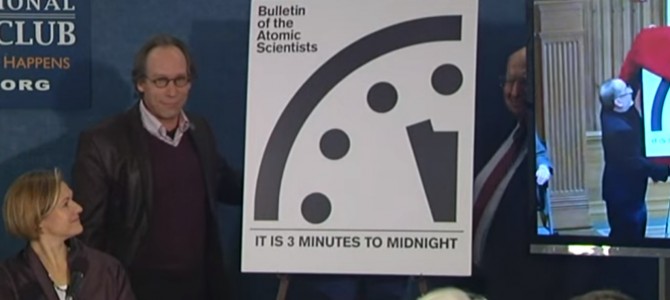

This week, a group of very smart people unveiled the hands of the famous “Doomsday Clock.” Like last year, it’s set at three minutes to “midnight,” meaning we are, at least metaphorically, perilously close to a global cataclysm of some sort.

Relax. We’re no closer, and no further away, from the apocalypse than we usually are.

The brainchild of a well-known journal called The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, the Doomsday Clock was kind of a big deal during the Cold War, mostly as a way for scientists to remind us (rightly) that we were always on the verge of blowing ourselves to Kingdom Come with nuclear weapons. The Bulletin is a great and venerable journal, even if I haven’t always agreed with its politics, and in its day, the clock was a harmless if thoughtful expression of anxiety about nuclear arms.

“Midnight” in those days meant a real apocalypse, a global thermonuclear conflict, rather than some notional climate-changed future in which London is kind of swampy. During the Cold War, the clock’s distance to midnight mostly depended on the state of affairs between the United States and Soviet Union. When times were bad and tensions were high, the clock moved closer to Armageddon. In 1953, when the hydrogen bomb was developed, we stood at two minutes to zero hour; when the SALT Treaty was signed in 1972, it moved back to 12 minutes.

The World Today Is Much Safer

Now, however, the clock is a kind of kitchen sink of stuff that worries particular cadres of scientists, and especially their liberal audiences: nukes, climate change, and generally being mean to each other. The position of the hands, insofar as they once reflected anything, now means nothing. In 2015, for example, we’re still supposedly four minutes closer to extinction than, say, in 1980, when President Jimmy Carter announced a sweeping new nuclear warfighting plan and Ronald Reagan took the presidency promising to confront the USSR head-on.

Indeed, we’re in a lot more danger now, according to the Bulletin and its scientists, than in 1991, when the clock (again, now at three minutes to The End Of All Things) was set at 17 minutes to go. This makes no sense: how could 1991 be the safest year ever, back when the crumbling Soviet Union was in the process of collapse while still in possession of tens of thousands of nuclear weapons? Back when the United States had thousands more strategic arms actively deployed, on even higher alert?

The world is a lot safer today, but no one is going to say that. No one can predict a “black swan” accident or miscalculation, of course, but one of the few things President Obama’s ever said that was perfectly accurate is that the world is generally more peaceful today than it was 40 or 50 years ago.

To assure people that things are more stable than they were 25 years ago, however, doesn’t make news, and it doesn’t advance an agenda. I doubt anyone really believes the world in 2016 is almost as dangerous as the days of Stalin and the H-bomb, but “things are generally safer than when you were a kid” is not a headline.

The Clock Is Political Theater Anyway

The clock, of course, doesn’t mean anything at all. It’s theater, a kind of events-driven political hypochondria. It’s whatever it needs to be to create a sense of urgent worry about things certain scientists think need urgent worry.

More important, the Doomsday Clock and the issues that now drive it aren’t about danger but about political power. Scientists, especially since the end of World War II, have been trying to figure out how to translate being smart in a narrow area—chemistry, physics, earth sciences—into political power. This is the old feud between science and policy, in which scientists give advice then are appalled when people and their leaders, for perfectly good reasons unrelated to science, reject it.

Scientists, understandably, have a hard time accepting that not everything is amenable to a scientific answer. For example, scientists were right that we were playing with fire during the Cold War, but we didn’t have much choice about that conflict because of decisions made by people in another country who were adherents of a dangerous ideology. (Sound familiar?) Setting the clock at one nanosecond to midnight wouldn’t have changed the fact that the Soviet Union still existed. No amount of laboratory know-how could change the fact that the Cold War was a political problem, not a quadratic equation.

Worse yet, scientists can sound ridiculous when trying to play in the policy arena, as was often the case during the Cold War. Exhibit A: the support of many scientists for the “nuclear freeze,” a proposal that would have prolonged, rather than curtailed, the arms race.

Leftists still believe the “freeze” moved Reagan toward arms control; that’s because they never understood Reagan, and in any case most of them have little idea what really happened because they were functionally frozen out of Washington in those days. Suffice to say that the Soviets were big fans of the freeze, which should tell you all you need to know, and Reagan wisely ignored it.

Scientific Knowledge Doesn’t Equal Wisdom

We’re seeing the same thing today. Last year, I ended up in a debate over the wisdom of the Iran deal during a symposium at Brown University, where Nobel Laureate Leon Cooper assured me that the science of the deal was solid. I didn’t dispute him on the technical details—who would?—but I asked what happens if political circumstances change.

What happens, I asked, if Russians decide to ignore cheating? What happens if Iran pulls out? “Bunker busters,” he answered, and when I said we didn’t have them, he shot back: “The Israelis do.” (I am not making that up. You can watch here.)

This is why people with Nobel Prizes in physics are not nuclear strategists. I wouldn’t argue with Cooper about the periodic table, where I’m certain he knows his beans. But if his fallback position in a negotiation is a proxy war run by Israel, I’m pretty sure he shouldn’t be making our non-proliferation policy.

If you’re a liberal and you’d like examples from the other side of the aisle, consider the career of Edward Teller, the father of the H-bomb. If you think scientists should run things, read up on Teller first. Likewise, the celebrated mathematician John von Neumann advocated preventive nuclear war. (Read that again: preventive nuclear war.)

“If you say today at five o’clock,” he wrote of nuclear war in 1950, “I say why not one o’clock?” Four years later, he was sitting in the Atomic Energy Commission. It’s easy to be a fan of scientists running things as long as it’s your own guys doing the science-ing, but scientists can be wrong about politics in all kinds of ways.

Scientists Are Manipulating You to Gain Power

This desire to translate scientific knowledge into political power is likewise at the root of the climate change debate. Climate change scientists who are trying to instill a sense of crisis in us with Doomsday Clocks aren’t telling us that we have to find better ways to continue our way of life while scrubbing carbon boogers out of the air, they’re telling us they don’t like what they see as under-regulated capitalism.

Having long ago lost the argument that technocratic socialists should run the business world, they’re now resorting to a time-honored tradition among scientists trying to seize the policy initiative: they’re not just saying “listen to me,” but “listen to me or we’re all dead.”

This is not Einstein worrying about nuclear war and peace in the next year, but a group of MacGuyvers jury-rigging wonky arguments together to gain control of the economy based on disaster in the next hundred thousand years. (Think I’m kidding about that long window? Read this.)

Climate change, of course, isn’t nuclear destruction, no matter how many labored metaphors about “slow-motion” Armageddon are brought to service that argument. Only Armageddon is Armageddon, and responsible diplomats and leaders are working on that. The rest of it is a scientific problem we’ll figure out over the next few centuries. (You do your job, scientists, and we policy guys will do ours.)

When the clock is just a general expression of a basket of liberal anxieties, it loses even the small metaphorical power it once had. I care a lot more about Putin’s finger on the Russian trigger—or, God help us, Donald Trump or Bernie Sanders controlling ours—than I do about whether Paris will be a beachfront property in 2270.

So my modest proposal to my friends at the Bulletin is either to change the clock back to a measure of actual nuclear danger from the arms race, or to retire it. Personally, I’m hoping we’ve seen the last of the Doomsday Clock. It was a well-intentioned warning during the Cold War, when counting down the minutes to all-out war was understandable. Today, counting down the minutes to—well, to whatever it is that seems to be scaring Nobel Laureates in any given year—makes no sense and trivializes one of the iconic images of the Cold War.