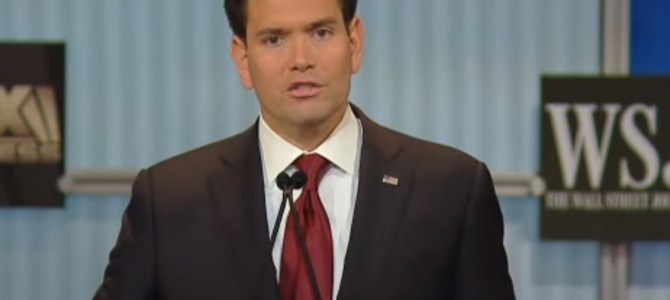

Marco Rubio took social media by storm Tuesday night with his declaration that America has a dearth of welders and an excess of philosophers. Welding, he informed us, is more lucrative, and more needed.

Within hours, multiple sites had slammed Rubio with pieces like this, purporting to prove that Rubio was wrong. For philosophers, the mean annual salary is 70,000 a year. Welders come in at a lowly 40 grand. Take that, brainiac.

Rubio was making a legitimate point in a foolish way. The rebuttals, however, have been equally sloppy. Rubio is quite right that for most young Americans welding would be a much sounder career choice than academic philosophy. On the other hand, philosophy is genuinely valuable, and poking fun at the Greeks (as Rubio is wont to do) is a dreadful way of pointing out the deficiencies of higher education.

Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up To Be Philosophers

The question that provoked this contentious line concerned minimum wage. The Democrats have been throwing around extravagant promises of higher minimums and more benefits, so Republicans need to answer by explaining how they’ll help struggling parents put food on the table. Rubio talked about the importance of a healthy, pro-business economy, then offered a final tip: become a welder, not a philosopher. Vocational training is a better way to earn money.

This is good advice for just about anyone who is concerned about minimum-wage laws in the first place. Yes, it’s true that (tenured) academic philosophy is nice work if you can get it. I would imagine the same could be said of working as a sportscaster, or being a rock legend. But we don’t often advise children to pursue those jobs, because they’re very hard to get, and an enormous up-front investment is required to put them even within the realm of possibility.

Likewise academic philosophy, which demands about a decade of study (give or take), followed by an abysmal slate of job prospects. Many people who go this route find themselves stuck at 30 with a Ferrari-level back-pocket degree and no job, money, or future prospects.

This graph, currently making the rounds, is absurdly misleading. Of course, it doesn’t count the scores of people who spend years studying for a job they never actually get. On top of that, it doesn’t appear to factor in the large numbers of PhDs who fritter away years of their lives working as adjuncts for minimal pay and (often) no benefits.

Those who gleefully forwarded this chart to all their friends need the experience of standing in line at the American Philosophical Association’s job fair in December, waiting to be tagged and numbered as an officially-recognized job-seeker. This hell-hole of cynicism and despair is filled with once-promising students who peer into the abyss of looming unemployment, trying to figure out why nobody explained to them, six or eight or ten years earlier, that money and employment make adulthood much more palatable. If they’d only become welders, these people would probably be several years into a secure career already, feeding their kids and everything.

It’s harder to find data on un- and underemployed would-be academics, but depending on who gets counted as a “philosopher” I think it’s likely that Rubio’s point could be sustained. His broader point is undeniable: we need to be more practical about urging people to get from high school to their first adult job in reasonable time, without taking on mountains of debt.

Soft Skills Aren’t Just for Special Snowflakes

Why, then, was Rubio’s comment “foolish”? Pitting philosophers against welders muddies the waters in two ways. First, it is an “apples and oranges” sort of comparison. Philosophy and welding aim at dramatically different ends, so the question of which is more valuable is basically unintelligible. Second, there are much better ways to illustrate the frivolousness of the modern university than by disparaging some of the most brilliant and influential thinkers in the history of the human race.

How many people actually find themselves choosing between the Ivory Tower and a career in welding? Exceedingly few, I would warrant. There are social reasons for that, but it’s also a reflection on the sorts of skills and talents required for each. Some people are very adept at working with their hands. For those people, vocational training may offer a promising path to a respectable career. Other people are more adept with words, numbers, or abstract ideas. In our information economy, we need those people, too, but perhaps not in a workshop. Nobody wants a clumsy welder.

In America today, too many people go to college. That’s because undergraduate education has turned into a status symbol and a gateway to middle-class respectability. We should work to change that so people who are (say) inarticulate but manually gifted aren’t forced to wade through years of expensive literature classes before getting the job that’s really appropriate for them.

It would be equally wrong, however, to recommend vocational training to all and sundry, and for those who are analytically inclined, the study of philosophy can do much to hone the skills and talents that employers actually need.

Philosophy makes an easy target for criticism because it tends towards the abstract. As a philosophy major in college, one becomes quite accustomed to answering the skeptical question, “But what are you going to do with that?” Studies show, however, that post-graduation philosophy majors are doing quite well in a wide variety of fields. It turns out that serious intellectual training really can help people to actualize talents and abilities that can then be applied to other fields.

Soft skills are also nice in that they are, by nature, adaptable. It was ironic how Rubio brought up welders not ten seconds after his warning that machines might render many human jobs obsolete. Who is in greater danger of being replaced by a machine: the welder, or the philosopher?

The other thing we should realize about philosophy is that its richest benefits can generally be unlocked only with the help of good pedagogy. Good professors are enormously important for critiquing and challenging a developing intellect.

Is this equally true of, say, a business major? I suspect not. Many practical subjects can be learned through correspondence courses or online streaming. For a good liberal arts education, contact with professors is enormously valuable. We should keep that in mind before we make a mad dash towards gutting all our liberal arts programs.

It’s All Greek to Rubio

Rubio really needs to take a seminar on Aristotle. I think he’d love it, and perhaps then he would stop raining scorn on men who embodied many of the ideals that conservatives (including Rubio himself!) hold most dear. And I’m not just saying that because I love Aristotle enough to have named a child for him. (It’s only the middle name. He doesn’t even have to tell the kids at school.)

When I introduce the Greeks to my introductory ethics course, I explain to my students: “You may not know anything about these people, but they said things thousands of years ago that changed the way you, here in modern America, see the world. These are giants of human civilization.”

Not everyone needs to read the Greek philosophers, but some people should. Greek philosophy helps us understand what it means to be human. It sheds light on who we are as a society, and on how we got this way. These are absolutely critical texts for anyone who would understand the human condition more fully. Bashing the Greeks isn’t quite as bad as dismissing the Bible, but it’s moving into that territory. Historically, most people who loved the one have also valued the other.

By contrast, the modern university is filled with small-minded tinkerers who waste countless taxpayer dollars running studies on useless or obvious things. It is filled with “grievance study” departments, in which whole groups of people devote years to revisionist history and whining about “privilege.” It is filled with overpaid administrators who draw six-figure salaries so they can spend their days trying to game the U.S. News and World Report rankings.

Against all of this, you’re going to reserve your contempt for the intellectual pillars of Western Civilization? Come on, Rubio. That just makes you look like a young Keanu Reeves, which is not what the Republican Party needs.

By all means, let’s rail against the wasteful impracticalities of higher ed! It’s got plenty of pork to spare. In the process, however, let’s not make ourselves look like illiterate rubes who care for nothing but widget-making. Philosophy has value, and so do welders. A healthy society must find ways to value both.