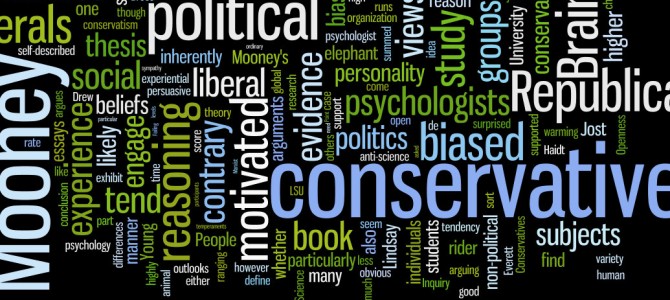

Chris Mooney’s The Republican Brain: The Science of WhyThey Deny Science – and Reality argues that conservatives are inherently more biased than liberals due to psychological differences that are likely partly genetic. To some this may seem almost too obvious to be worth stating. For others, particularly for conservatives, the thesis is liable to provoke a strong reaction. Indeed, Mooney described the book as setting a trap for conservatives. Any criticism of the book’s scientific conclusions can be taken as more evidence for the book’s thesis that conservatives are biased and reject science.

The irony here is that Mooney’s thesis – conservatives are inherently more biased – itself runs contrary to the views of many social psychologists working in this area. The current de facto position of social psychologists is summed up by University of California-Irvine psychologist and self-described liberal Peter Ditto (who Mooney quotes in the Republican Brain): “When I’m at home, I spend all my time, like a good liberal, yelling at the television set, denouncing Republicans and how biased they are. Then I assume my persona at work and I say, theoretically, it’s really hard to know why there would be a difference.”

Man is a Rationalizing Animal

That’s not to say that The Republican Brain is all wrong about the connection between politics and personality. Psychological research has found connections between a person’s temperament and their political views, with certain personality types inclined towards conservatism and others towards liberalism. For example, self-described conservatives tend to score higher on personality tests in terms of Conscientiousness, which is characterized by high levels of self-discipline, dutifulness, and organization. Self-described liberals, meanwhile, tend to score higher on Openness to Experience, which is characterized by an inclination towards novelty, variety, and creativity.

The idea that conservatives and liberals tend to have different temperaments is hardly new. You can find hints of the idea in sources ranging from Thomas Sowell’s A Conflict of Visions to ordinary political humor. As with any generalization, there will be exceptions; some liberals will be highly conscientious while some conservatives will be highly experiential. Overall we should not be surprised that conservatives tend to be overrepresented in fields that prize conscientiousness (such as business and the military), while liberals are more drawn to experiential areas such as the arts and the academy.

In addition, there is a great deal of psychological research establishing that, pace Aristotle, man is not only a rational animal but is also a rationalizing animal, particularly when it comes to politics. When confronted with evidence that goes against their pre-existing beliefs, people do not response by objectively evaluating it. Instead, they tend to respond emotionally, attacking or dismissing contrary however possible, while credulously accepting any evidence or authorities that seem to support their view. Anyone who has spent time arguing politics on the Internet will not be surprised at this finding.

Again, these are tendencies, not universals. People can rationally assess contrary arguments, it just doesn’t come naturally. The social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, (whose book The Righteous Mind covers some of the same ground as The Republican Brain but without the partisan overlay) uses the metaphor of a rider sitting atop a giant elephant. The rider is our reason; the elephant, our instincts, emotions, and psychological needs. The rider can move the elephant, but it’s not easy.

Are Conservatives Worse?

Where The Republican Brain departs from Haidt and other social psychologists is in claiming that conservatives are more likely to engage in motivated reasoning in defense of their politics. That’s a much harder case to make, and here Mooney falls short.

Mooney devotes a good part of the book arguing that modern day conservatives are wrong on a whole host of issues ranging from global warming to the effect of Obamacare on the federal deficit. For obvious reasons, these arguments are more likely to appeal to those who share Mooney’s liberal politics.

But even if he were right in every case, this wouldn’t be sufficient to justify the claim that conservatives are inherently more biased. To do that, you would have to show conservatives have been more biased and anti-scientific over the whole scope of human history. When one considers left-wing sympathy for pseudo-scientific theories such as Marxist economics, Lysenkoist biology, or Freudian psychoanalysis, there is reason to be skeptical.

The “asymmetry thesis” also runs contrary to social psychologists’ understanding of how motivated reasoning works. Dan Kahan recently summed up this point nicely:

People have a big stake–emotionally and materially–in their standing in affinity groups consisting of individuals of like-minded goals and outlooks. When positions on risks or other policy relevant-facts become symbolically identified with membership in and loyalty to those groups, individuals can thus be expected to engage all manner of information–from empirical data to the credibility of advocates to brute sense impressions–in a manner that aligns their beliefs with the ones that predominate in their group.The kinds of affinity groups that have this sort of significance in people’s lives, however, are not confined to “political parties.” People will engage information in a manner that reflects a “myside” bias in connection with their status as students of a particular university and myriad other groups important to their identities.Because these groups aren’t either “liberal” or “conservative”–indeed, aren’t particularly political at all–it would be odd if this dynamic would manifest itself in an ideologically skewed way in settings in which the relevant groups are ones defined in part by commitment to common political or cultural outlooks.

To support his thesis, Mooney cites a 2003 meta-analysis of 88 separate surveys comparing personality and political views, conducted by a team of psychologists headed by John Jost of New York University. The Jost study found conservatives were more likely to exhibit dogmatism, intolerance of ambiguity, and general closed-mindedness.

One of the most decisive rejoinders to this cames from Ronald Lindsay, who was also Mooney’s boss (Lindsay is President and CEO of the Center for Inquiry, a non-profit organization that hosted Mooney’s Point of Inquiry podcast). As Lindsay noted, many (though not all) of the underlying studies used in the Jost analysis define conservatism by relying on the “Wilson Patterson Scale,” which categorizes individuals as conservative based on whether they exhibit characteristics such as a “superstitious resistance to science.” Unsurprisingly, if you define someone as conservative if they are anti-science, then it turns out that conservatives tend to be anti-science.

Mooney’s main argument, though, has to do with the ideological differences in openness to experience. Since liberals are more open to experience, Mooney argues, it stands to reason that they would be more open to contrary points of view, and so will feel less need to use motivated reasoning to swat down evidence that conflicts with their own cherished beliefs.

Failing the Test

It’s an interesting theory, but unfortunately for Mooney, some of the strongest evidence against the theory is set forth in The Republican Brain itself. In the last chapter of The Republican Brain, Mooney describes a study he helped design and carry out along with Everett Young, a psychology post-doc. In the study, students at Louisiana State University were quizzed on their political beliefs as well as their views on a variety of subjects both political (global warming and nuclear power) and non-political (Lady Gaga and Drew Brees). They were then presented with short essays that either supported or criticized their prior views. After reading the essays, the students were asked to rate how persuasive they thought they were, and whether they had changed their minds. [Full disclosure: I went to high school with Drew Brees and think he is a great quarterback.]

Given the human tendency to confirmation bias, one would expect participants not to change their minds much, and to find the essays that supported their views more persuasive than the ones that did not. What set the LSU study apart was that it specifically looked at whether this sort of bias was higher for conservatives on non-political subjects. This is significant, because according to The Republican Brain it is conservatives’ lower openness to experience that is supposedly responsible for their being more biased than liberals. Openness to experience isn’t limited to political subjects, so if less openness means more bias, conservatives ought to engage in more motivated reasoning even on subjects that aren’t remotely political.

Mooney clearly intended the study to be his coup de grace, the final, definitive proof that conservatives’ was leading them astray across the broad. There is only one problem. The LSU study failed to find any correlation between political ideology and the tendency to engage in motivated reasoning on non-political subjects. While the book doesn’t report findings as to openness, correspondence with Everett Young confirmed that higher openness to experience was not associated with lower motivated reasoning.

If openness to experience doesn’t mean openness to contrary evidence, then Mooney’s whole argument for why conservatives are more biased must fall by the wayside. That, at any rate, is the conclusion his co-author seems to have come to. “My feeling at the conclusion of this study is that motivated reasoning is not a psychological-ideological phenomenon,” says Young. “That is, conservatives and liberals do not differ in their level of motivated reasoning as a result of the inherent psychology that makes them conservative or liberal.”

Admissions like this are devastating to Mooney’s argument. Conservatives criticizing The Republican Brain can be dismissed as utterly predictable. But when Mooney can’t even convince intelligent, liberal-minded folks such as his own co-author or boss (not to mention many liberal social psychologists) that might just be an indication that his arguments aren’t compelling.