The 2026 midterms may be a year away, but the battle over rules governing America’s elections remains very much ongoing.

On Tuesday, the U.S. Supreme Court held oral arguments in National Republican Senatorial Committee (NRSC) v. Federal Election Commission (FEC), which centers on a challenge to provisions of the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) that restrict the ability of candidates and political parties to coordinate spending with one another. More specifically, the suit — which was brought in 2022 alongside the National Republican Congressional Committee, then-Sen. J.D. Vance, R-Ohio, and then-Rep. Steve Chabot, R-Ohio — contends that these limitations violate the First Amendment.

In his opening statement, NRSC counsel Noel Francisco argued that the “coordinated party spending limits are at war with [the Supreme Court’s] recent First Amendment cases,” and that the prevailing “theory is that they’re needed to prevent an individual donor from laundering a $44,000 donation through the party to a particular candidate in exchange for official action.” “But that Rube Goldberg theory,” he reasoned, “fails for the same reasons this Court rejected it in [McCutcheon v. FEC].”

“First, it’s unlikely to work because the donor has to cede control of his money to the party committees, which have their own interests. Second, it’s already prevented by other things, including the $44,000 base limit, the earmarking rule, disclosure requirements, and the bribery laws,” Francisco said. “And third, there’s no need for it since a would-be briber would be better off just giving a massive donation to the candidate’s favorite super PAC. That’s why no one has identified a single case in which a donor has actually laundered a bribe to a candidate through a party’s coordinated spending even though 28 states allow it.”

The NRSC’s arguments (unsurprisingly) faced pushback from the court’s Democrat appointees, including Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor. In expressing her concerns to Francisco about what would happen if SCOTUS were to “take off this coordinated expenditure limit,” the Obama appointee appeared to take a cheap shot at Elon Musk’s support for President Trump in the 2024 election and his subsequent appointment to lead the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE).

“You mean to suggest that the fact that one major donor to the current president — the most major donor to the current president — got a very lucrative job immediately upon election from the new administration does not give the appearance of a quid pro quo?” Sotomayor asked.

Francisco said that while he’s “not a hundred percent sure about the example that [Sotomayor’s] looking at,” if he “think[s] [he] know[s] what [she’s] talking about, [he has] a hard time thinking that his salary that he drew from the federal government was an effective quid pro quo bribery, which may be why nobody has even remotely suggested that to be the case.”

“Maybe not the salary, but certainly the lucrative government contracts might be,” Sotomayor replied.

Meanwhile, Roman Martinez, who was appointed to argue in defense of the restrictions after the federal government sided with plaintiffs, spent much of his speaking time arguing that SCOTUS should dismiss plaintiffs’ case as moot because there is an “absence of any real-world credible enforcement threat” and Vance has “repeatedly denied having any concrete plan to run for office in 2028.”

“Petitioners say that uncertainty is enough to prevent mootness. That’s wrong as a matter of law,” Martinez said. “Even if you disagreed with me about Vice President Vance’s standing because of his concrete plan to run, there’s also the absence of any real-world credible enforcement threat. The executive order bars the FEC from enforcing the law. No one thinks President Trump is going to enforce this law and target his own vice president.”

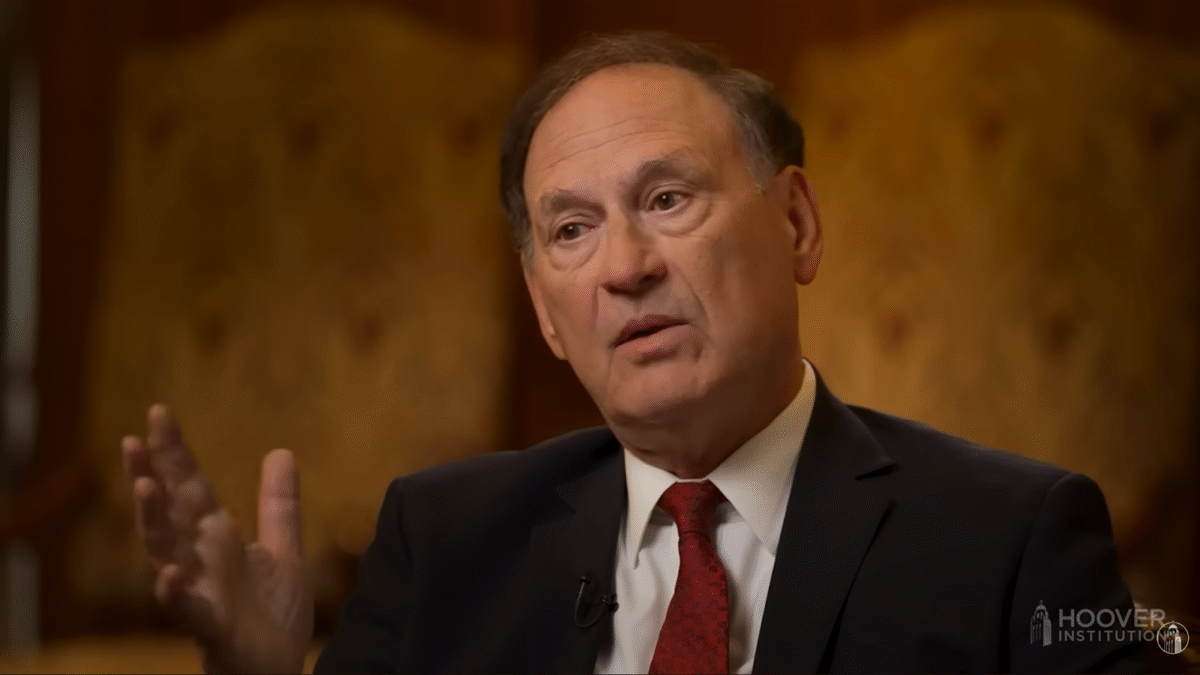

Martinez’s argument about Vance’s plans for the 2028 election didn’t appear to pass the smell test for Associate Justice Samuel Alito. The Bush appointee specifically pressed the attorney on “at what point” a vice president or a one-term president potentially seeking to run in the next election would “be able to challenge a provision like this.”

Under a hypothetical posed by the justice, Martinez denied that his standard would require such candidates to hire consultants and have a big event to announce his intent to run before they could have standing. He did say, however, that “the analytical question is when does he have a concrete plan,” at which point “you’re going to have to look to evidence in the public, in the record, etc. about what that plan is.”

“I’ll tell you when it’s not satisfied. It’s not satisfied when the candidate says in comments published today that a 2028 run is ‘something that could happen, it’s something that might not happen,'” Martinez said.

“Isn’t that what [all] potential candidates always say until the day when they make the announcement?” Alito asked. “That’s what they always say.”

Martinez went on to note that potential candidates who have and have not gone on to run for office employ such rhetoric. He then pivoted to Vance and claimed that “the easiest thing in the world” that the vice president could have done to address the alleged mootness issue was to “have come forward and … say, ‘I have a concrete plan [to run].'”

Clearly aghast, Alito asked, “I mean, are you serious — are you serious?” (Martinez responded that he was.)

Another particularly vocal justice during the hearing was Brett Kavanaugh. When questioning parties on both sides of the issue, the Trump appointee repeatedly emphasized his concerns about how the amalgamation of campaign finance laws and past Supreme Court decisions have “together reduced the power of political parties as compared to outside groups with negative effects on our constitutional democracy.”

“Should we be concerned about the overall architecture of our jurisprudence having weakened or disadvantaged political parties as compared to outside groups?” Kavanaugh asked Principal Deputy Solicitor General Sarah Harris, who argued in NRSC’s favor on behalf of the Trump administration.

“I think you should be concerned with that,” Harris said. “I think the even greater concern beyond the disadvantage to political parties that was wrought when FECA sort of overturned over a century’s worth of uninhibited coordination between parties and candidates is just the see-sawing of the court’s jurisprudence that would happen if Colorado II remained an outlier and remained in place to sow mischief.”

Also granted the ability to appear in Tuesday’s hearing was infamous Russia collusion hoaxer Marc Elias, who argued in opposition to the NRSC’s case on behalf of the Democratic National Committee. The left-wing attorney’s often incoherent ramblings were specifically called out by Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, who — after enduring one of Elias’ diatribes — said, “I still don’t understand what you’re saying.”

A decision in NRSC v. FEC is not expected until sometime next year.