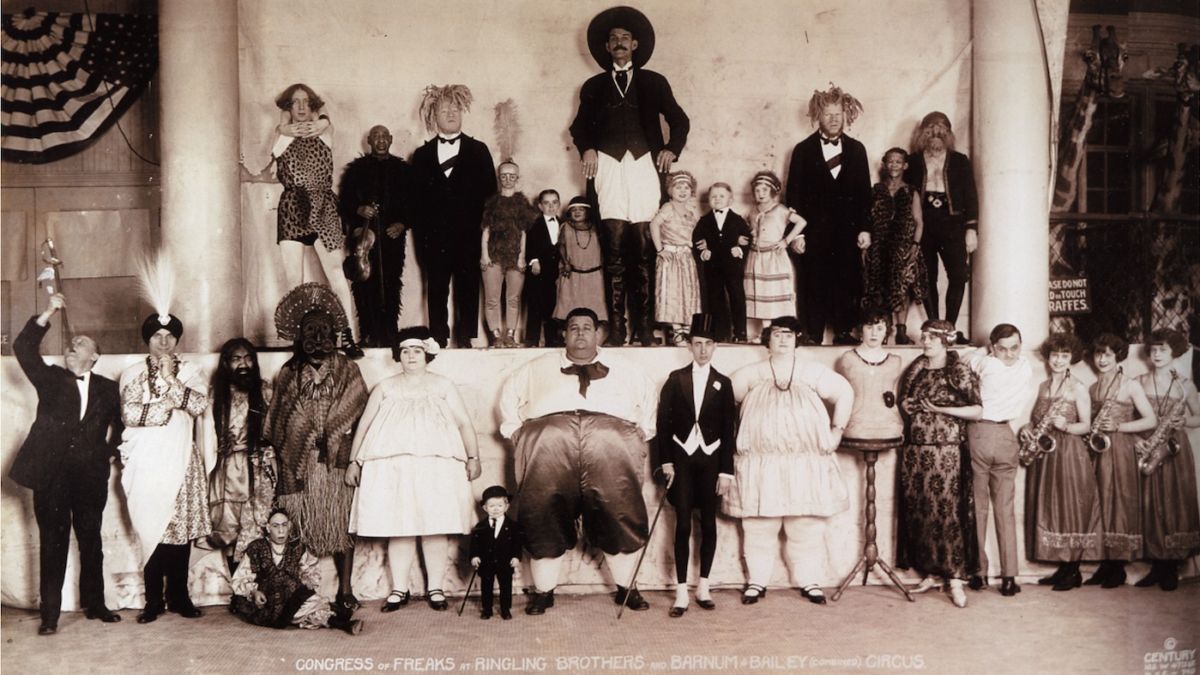

For Baby Boomers, this famous quote, attributed to Joan Collins, humorously captures a change many of them have observed in American society during their lifetimes: “Grandmother used to take my mother to the circus to see the fat lady and the tattooed man — now they’re everywhere.”

The reality behind the quote is that over the past few decades, American society has largely abandoned standard norms — of appearance, language, and behavior — in favor of a far more à la carte, each-to-their-own choice of how individuals should or can present and conduct themselves in society.

Fashions, standards, and mores evolve in all societies. What differs about the sea-change in this area since the late 1960s, however, is that rather than having one set of conventions gradually replace another, there has been a progressive withdrawal from the very idea of externally perceivable norms as the unwritten framework for what mainstream society considers acceptable and unacceptable.

The new “normal” is a near-absence of norms.

To hark back for a second to the Joan Collins quote, the example of the general spread of obesity and tattoos — once so marginal as to be limited to unfortunate occurrences of glandular dysfunction in the former case, and sailors and convicts in the latter case — is emblematic of not only those things now accepted or even celebrated, but of their co-existence with every other possible manner in which people today choose to present themselves in society, from Goth fashion, to sportswear as everyday attire, to the fetishization of bulbous buttocks, to social media selfies photoshopped to the outer extremes of the possibilities of the human physique.

And we have witnessed, in the past few years, the deconstruction of perhaps the oldest societal norm of all — the distinction between the two biological sexes — into the current very loud controversy over gender fluidity and pronouns.

“What’s the harm in that?” many will ask. And indeed, at the surface and individual level, this kaleidoscope of tastes, fashions, and projected identities can be seen as the simple continuation of the trend toward individualism that started as far back as the late Middle Ages.

But, at the collective level, real dangers come when a society moves from a framework of standards to a culture with virtually no common standards at all.

Shaped gradually over centuries by collective and implicit agreement on what was seen as desirable or healthy for both the individual and for society, norms have traditionally expressed a society’s values. For the most part, they were not enforced by the law, but rather by the sense of shame that society’s disapproval would trigger in those who transgressed such norms.

The softer side of these once-ubiquitous societal norms was called “etiquette,” or, more generally, basic good manners. Their traditional function was to ensure a certain decorum and civility among people. One intent was to shield those perceived at the time as more vulnerable or delicate from unpleasantness and vulgarity, as seen in the lost norm that men should avoid foul language in front of women and children.

Proper etiquette also served to prevent distasteful and annoying behavior in social interactions (not chewing with an open mouth, not speaking with a mouth full of food, moderating volume of speech) as well as to demonstrate respect or appreciation for others or for places of hospitality (not wearing hats indoors, bringing a small gift when invited to dinner). These types of observances were seen as the tangible outcome of a “good upbringing,” thus constituting positive societal reinforcement for the parents of the well-mannered individual.

The infringement of a norm implies a judgment is being passed. And in today’s culture, being accused of being “judgmental” is akin to being labeled intolerant, hateful, bigoted, or worse. Passing judgment is the antithesis of what seems to be the only universal virtue left in modern society: being non-judgmental, or, to put it simply, being “nice.”

Disapproval of pretty much anything has been replaced by the need to be seen as positive, caring, understanding, tolerant, empathetic, open-minded, solicitous, and generally kind-hearted. Hence the virtue-signaling flooding social media and the decline of fire-and-brimstone religion, which has been increasingly replaced by the “positivity” of its modern-day substitutes such as meditation, yoga, and “holistic wellness.”

Culturally, being “nice” equates with the judgment-free acceptance of all forms of fashion, art, music, personal identity, and language, no matter how aesthetically unappealing, cacophonic, vulgar, or simply preposterous. Politically, the mantra of niceness has given rise to forms of moral relativism in public policy that have resulted, for example, in cash-free bail, the decriminalization of certain forms of theft and other crimes, the widespread legalization of marijuana, cities flouting federal immigration law, and the focus on historical revisionism.

But what has replaced the self-conscious self-regulation once underpinned by societal norms?

The prevalence today of morbid obesity, the universal spread of profanity, the wearing of unflattering or inappropriate clothes, the popularity of extensive tattoos and piercings, the rise of widespread drug abuse, the brawling in theme parks and aboard commercial aircrafts, and the problem of increasing criminal violence all point to a culture off track. Our culture has abandoned the standards that existed two or three generations ago — in terms of what they considered healthy, positive, and generally appealing for both individuals and for society as a whole.

Those with a “progressive” bent will decry this line of reasoning, arguing that aesthetics is by its very nature subjective, that “fat shaming” is a reprehensible form of social cruelty, that formerly illegal drugs have merely taken their place alongside tobacco and alcohol, and that crime and violence are merely symptoms of an unjust society. No amount of evidence or logic will sway such views.

But the abandonment of standards brings a far more damaging societal consequence, and it is hiding in plain sight: the creation of a highly visible and most often irreversible distinction between elite society and, for want of a better term, “the masses.”

This phenomenon can be witnessed most easily in those places where the affluent and the privileged, as well as the moderately successful — let’s call them “the 10 percent” — live in close proximity to the remaining 90 percent, and particularly to those fellow citizens considered “the underclass.”

In these tony neighborhoods — from New York’s Upper East Side to Los Angeles’ Beverly Hills, from Washington, D.C.’s Georgetown to Chicago’s Gold Coast — the obese, the heavily tattooed, the eyebrow-studded, the inarticulate, and the badly dressed are found rarely and readily identified as “not belonging” by these neighborhoods’ slim, elegant, and urbane local residents, as well as by the doormen, security staff, and shop assistants they employ.

The resulting subtle apartheid demonstrates the law of unintended consequences: the loosening of societal standards, thought to increase freedom of lifestyle choices and self-expression, has also resulted in the creation of a quasi-caste system in which the plus-sized, the inked, the unintelligible, and the shabby or sloppy are — de facto if not de jure — denied the ability to compete for jobs, for mates, and generally for opportunity in the residential enclaves and in the professional sectors of the rich, svelte, chic, and highly educated.

This is the real tragedy of a pendulum that has swung too far from conformity to “anything goes.” For these readily identifiable non-elites, social and professional upward mobility is today blocked by the very jettisoning of standards that was advertised as the path to a more modern, tolerant, free, and fluid society.

Instead, we have a culture that is undoubtedly coarser, more unattractive, and more confrontational than it was in the recent past and, most importantly, one in which a large social class of “plebeians,” constituting an absolute majority of the population, is now limited in its aspirations — not just by education, generational wealth, and family connections — but now by language, behavior, and physical appearance as well.

The result feels like a cruel trick played by the elites on their less fortunate fellow citizens, preventing anyone from below from joining their ranks. Yet the abandonment of normative societal standards has not been imposed from above. It is instead a cultural spin-off of the wider anti-establishmentarianism of the late 1960s.

It “felt right” at the time to throw off the shackles of convention across a broad range of former norms in a range of cultural domains. But the trendsetters of the time did not anticipate what happens in a cultural vacuum.

Societal standards — whether in dress, language, body shape, or behavior — have existed since the beginning of civilization for a reason. We abandoned them, for the first time in human history, against logic and at great cost. And those who can least afford it pay the highest price.