The Group of Seven (G7) nations, including the United States and six other wealthy countries, recently announced they had reached an agreement to impose a minimum global corporate tax rate on multinational companies and would be amending long-held international tax principles and rules. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen hailed the announcement as a victory that would end the global “race to the bottom” on taxation. But in truth, what the G-7 proposed is a bad deal for America’s sovereignty, American businesses, and taxpayers.

The agreement has two main components. The first is to implement a new tax rule. Currently, corporations pay taxes over profits earned to nations where they have a physical presence. The G-7 agreement proposes that countries would have the right to tax 20 percent of profits above a margin of 10 percent where the company’s products or services are consumed.

For example, Company X is located in County A but sold its service to people in Country B. Company X made a profit of $15, representing a 15 percent profit margin. Under the current global tax system, Company X has to pay tax on the $15 profit to Country A only. According to the new G-7 agreement, however, Country B will also collect 20 percent tax on the profit above a margin of 10 percent, which in this case is $5.

While clearly aiming at American tech giants, this G-7 proposal is, in fact, a global digital service tax in disguise. Out of concerns for “fairness” and “justice,” in recent years some European governments have called for imposing a special digital tax on large U.S. tech companies. Nevertheless, with rare bipartisan support, the Trump administration had pushed back on such attempts, arguing the digital tax amounts to discrimination against the American companies in question.

Surrendering to European Demands

Last July, France demanded that tech companies with revenues of more than 25 million Euros in France and 750 million Euros worldwide to pay a 3 percent digital service tax on digital income generated by French users. The Trump administration retaliated by imposing levies on French imports to the United States, but the Biden administration suspended these levies in January.

Then the United Kingdom, Spain, and four other countries declared that they would impose their version of the digital service tax. In response, the Biden administration announced 25 percent tariffs on more than $2 billion worth of imports from these six countries but quickly suspended the tariffs to provide further time for negotiations to bear fruit.

According to a Politico report from Mark Scott and Bjarke Smith-Meyer, the spat between the United States and European nations over the digital tax was not about money (at most, a global digital tax will generate $100 billion a year), but about control over the digital economy. The recent G-7 agreement on a global digital tax, however, seems to suggest that rather than negotiating and fighting to protect the interests of American companies, the Biden administration has given up such control.

In the words of the Wall Street Journal’s editorial board, the Biden administration has “acquiesced to European demands that the tax be tailored so narrowly that it would apply primarily to U.S. digital companies and not large European manufacturers.” In doing so, the Biden administration surrendered “Washington’s ability to tax American companies as Congress sees fit.”

What of the ‘Race to the Bottom’?

The second component of the G-7 proposal is to impose a 15 percent minimum corporate tax for multinational corporations. Any companies that pay less than that rate in one country will have to make an additional tax payment to their home country.

Jeff Goldstein of the Atlantic Council provides an example of how the global minimum tax works: company X is headquartered in Country A, which has a corporate tax rate of 20 percent but reports income in Country B, where the corporate rate is 11 percent. Given that the global minimum tax rate is 15 percent, Company X would have to pay Country A an additional 4 percent tax on its profit reported in Country B, which is the difference between the global minimum of 15 percent and Country B’s corporate tax of 11 percent.

The idea behind such a proposal is to reduce the incentives for corporate inversion, a tax strategy some multinational companies deploy to reduce their tax liabilities by relocating operations to countries with much lower corporate tax rates than their home countries. Ireland, for example, is known for its low corporate tax of 12.5 percent and is home of such well-known American companies such as Medtronic and Seagate.

Some governments complain the current tax system costs between $200 to $600 billion in revenue each year. They see a global minimum tax scheme as a way to reduce corporate inversions, keep corporations and jobs at home, and provide governments a floor of tax revenue. But the right way to discourage corporate inversions and retain businesses and jobs at home is to cut domestic corporate tax rates, not to demand other nations raise their corporate tax rates.

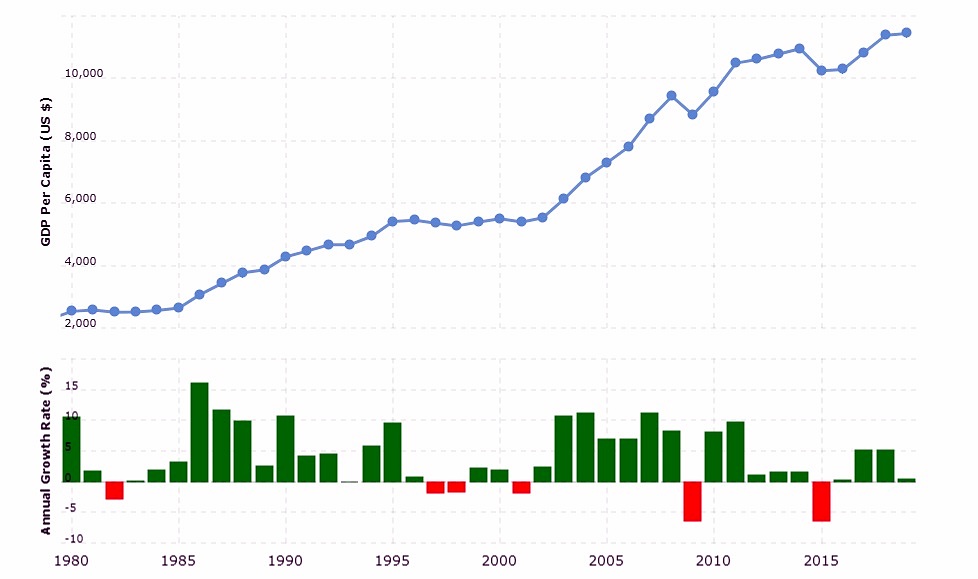

History has shown the so-called global “race to the bottom” on taxation has fueled global economic growth – indeed, the worldwide average statutory corporate tax rate had dropped from 40 percent in 1980 to 24 percent in 2020. For example, the world GDP per capita has grown from $2,533 in 1980 to $11,422 in 2019. As a result, governments have collected more revenue from economic growth.

The Persistent Question: Who Benefits?

A global minimum tax is a bad idea because every nation faces a different set of challenges. What works in one country doesn’t necessarily work for another one. It’s within every nation’s sovereign right to decide what taxation policies are best for them.

Once in place, a global minimum tax is a violation of an individual nation’s sovereignty because it will take away a respective nation’s ability to set competitive tax rates as they see fit. This explains why China is unlikely to agree to a global minimum tax because the Communist Party will never relinquish its control of China’s tax policies.

Why then, does the Biden administration think it is a good idea to surrender some control of setting America’s tax policies while limiting the ability of future administration to set competitive tax rates?

Some may argue the proposed global minimum tax at 15 percent is much lower than the Biden administration’s initially proposed 21 percent. Such a low rate will only negatively affect a few counties today, and it leaves sufficient room for future U.S. administrations to set competitive tax rates should they choose.

Yet even at a global minimum tax rate of 21 percent, an extremely optimistic estimate shows it will only raise an additional $600 billion for all nations involved to share. Hence, a global minimum tax rate of 15 percent will collect an even smaller amount.

Don’t expect the revenue from a global minimum tax to either make a dent in paying back the trillions of debt that governments accumulated or make any difference for the trillions more they plan to spend. Once the mechanism of a global minimum tax is in place, it is only a matter of time before some member nations call for an increase.

The Long, Perilous Road Ahead

Even if the Biden administration succeeds in keeping all the U.S. corporations onshore by imposing a global minimum tax and resetting the U.S. corporate tax rate at 28 percent, it will raise only about $700 billion in 10 years, hardly enough to pay for the administration’s $6 trillion annual budget.

Joseph C. Sternberg of the Wall Street Journal concludes, “no one inside the administration or out can seriously believe corporate taxation is going to play a major role in paying for” the Biden budget, so the political purpose of focusing on corporate taxation now is “to make personal taxes — the kind voters care deeply about — easier to raise in short order.” Sooner or later, America’s middle class should expect to pay more taxes to fund the Biden administration’s excessive spending.

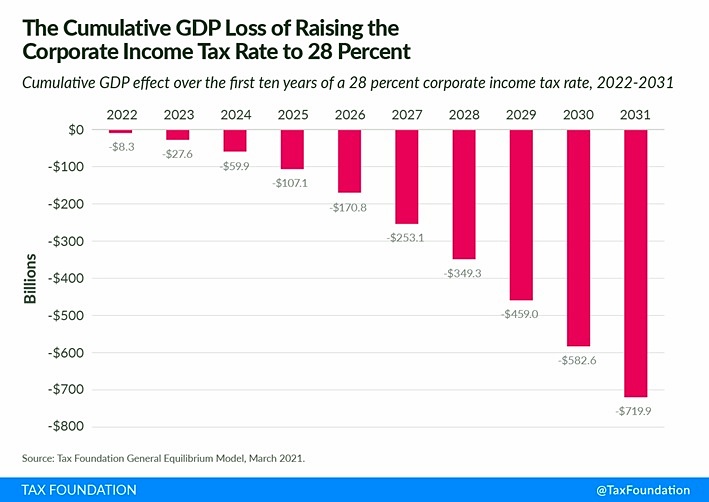

America’s middle class will have to pay in other ways too. For example, the Tax Foundation estimates that a 28 percent corporate income tax reduces investment and economic growth, resulting in a $720 billion GDP reduction over ten years, translating to fewer jobs and lower wages for American workers.

The G-7 agreement on taxation faces a long road ahead to be adopted by more than 100 countries worldwide. As an international treaty, it requires approval from the U.S. Congress. If Americans are fortunate, enough members from both sides of the aisle will reject the G-7 agreement on taxation, as, ultimately, it’s simply a bad deal for U.S. sovereignty, the nation’s businesses, and taxpayers.