The recent article “I Can’t Get My Hip Surgery Because Of Coronavirus Even Though Nobody Is In Our Hospital” highlighted the very real problems coronavirus has created in all our communities. It is true that necessary preparations have compounded challenges and left many suffering in ways that are not immediately obvious. As a physician dealing with COVID-19, I have a different perspective.

My heart goes out to you, Anonymous. I am so sorry your surgery has been delayed, your plans wrecked, and your pain prolonged. It’s hard, and it’s not fair. You bring up a valid point that the enormous splash of the Wuhan virus can make it easy to overlook the expanding ripples, which reach into every person’s life. Indeed, it is hard to imagine anyone anywhere who has not been affected by this pestilence.

There’s not much I can say to make it easier. I want you to know your suffering is not going unnoticed.

The Wave Is Still Coming

You are right that hospitals have been emptied in anticipation of a wave of COVID-19. In some places, that wave hasn’t yet arrived. I know some people are concerned this may be an overreaction, but I would caution them against jumping to conclusions. This thing is far from over; it isn’t even halftime yet.

It may seem odd that hospitals are empty as planned medical procedures are canceled. You’re right that “elective” doesn’t mean “unnecessary,” just “not an emergency.” To have any procedure, however, even one less invasive than hip surgery, risks exposing the patient and everyone with whom he interacts to COVID-19. We know the virus can attack anyone, but it preys especially on those whose health status is marginal. Simply put, to subject your body to the stress of surgery and recovery would put you in danger needlessly.

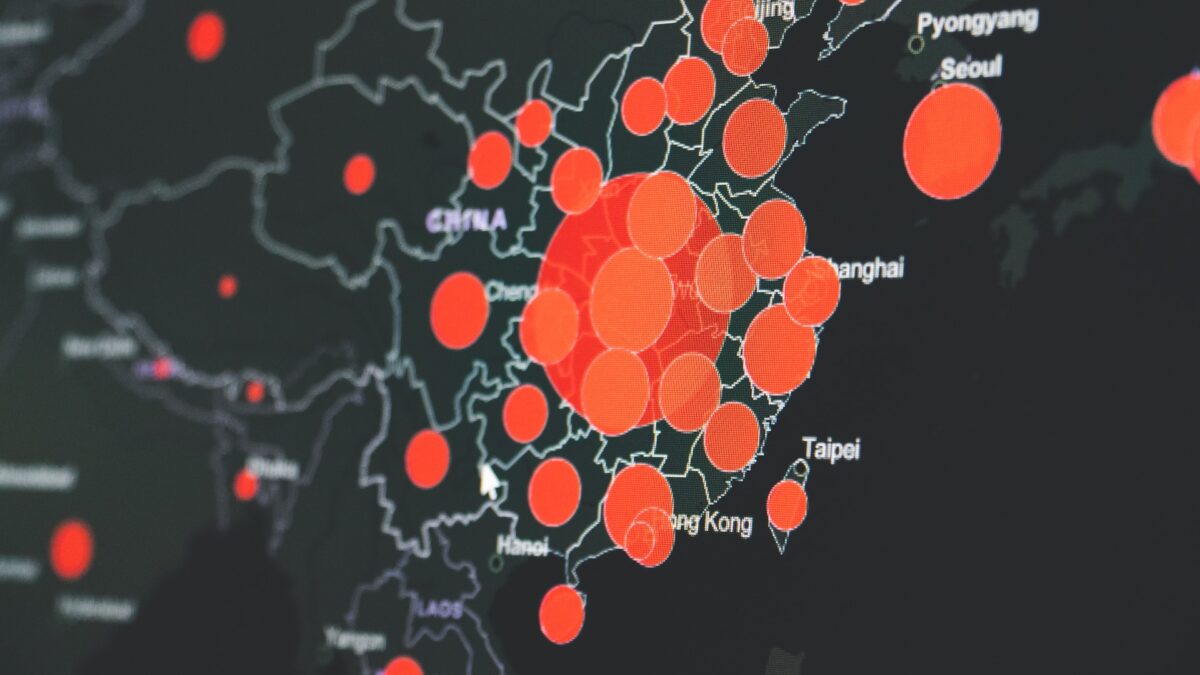

While the true extent of the damage in China has likely been severely understated, the whole world saw what happened in Europe, first in Italy then in Spain. Medical professionals everywhere said to themselves in February, This is coming here. Italy didn’t have time to prepare, but we do. If we don’t make use of the time, we will experience a similar tragedy.

Sure enough, the wave appeared on our shores: New York, New Jersey, San Francisco, Seattle. By the time we had our preparations well underway, we had an even more vivid demonstration of what we would see if we didn’t expand our capacity to care for patients by every possible means.

Granted, we don’t know exactly how quickly this will progress, and at the beginning of March we knew even less. It wouldn’t hit everywhere at once, but like any wave, it would wash across the country. While it would hit big cities sooner, rural areas couldn’t expect to be spared, and they may be less capable of absorbing a sudden spike in illness.

Hospitals Are Trying to Be Prepared

I illustrated this to my friends and family with simple back-of-the-envelope math. Our town has a population of about 20,000. Suppose one person in 10 in our small town were to get the virus in a relatively short timeframe. It’s unlikely but not completely implausible: the tiny city-republic of San Marino in northern Italy hit the 10 percent mark. In my town, that’s 2,000 people.

CDC estimates that of those who get sick, roughly 80 percent will be affected mildly, 15 percent will be severely ill, and 5 percent will be critically ill. That means of those 2,000 people, 300 will be severely ill — more than three times the capacity of our hospital.

We would need up to 100 ventilators for the 5 percent who are critically ill, and we have far, far fewer than that. Imagine this in every small town in America, and proportionately more in larger hospitals. While models varied widely, some suggested even worse scenarios. The scale of this pandemic could be catastrophic, and that isn’t hyperbolic.

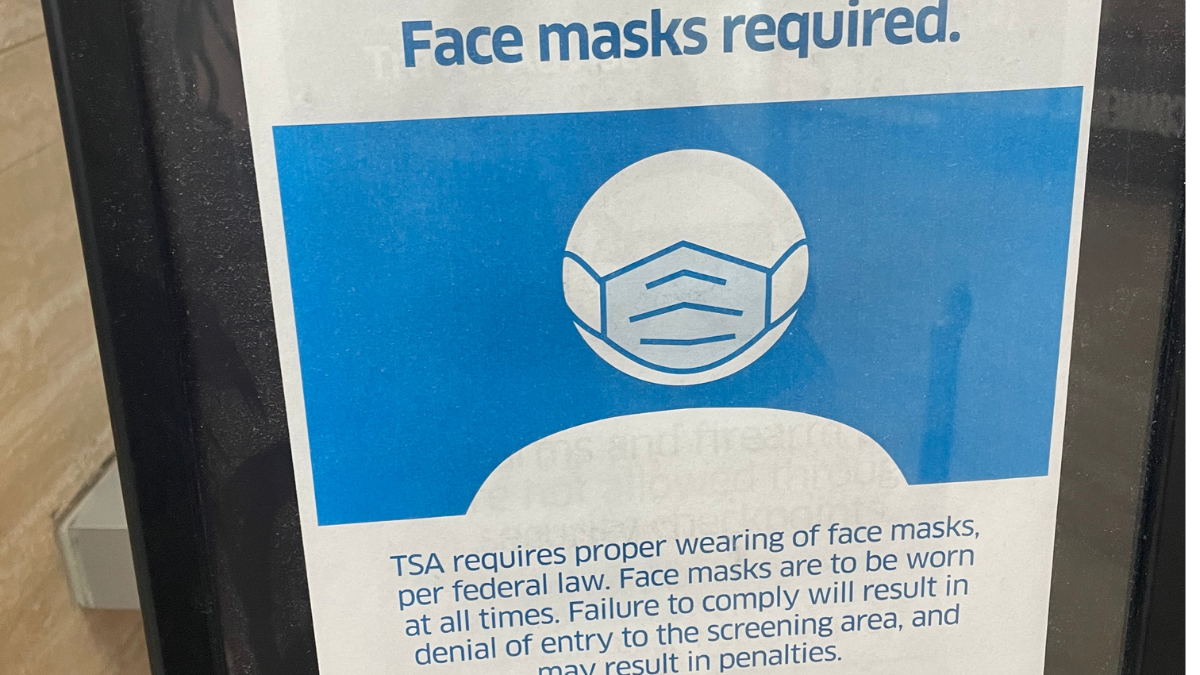

Our hospital started a respiratory triage clinic, open 12 hours a day and six days a week. It is run with two goals: 1) Keep sick patients out of primary care offices, and 2) keep patients who aren’t truly desperately sick out of the emergency room. Offices are down to skeleton crews to minimize exposure but are still committed to taking care of patients who simply need to receive regular care.

Make no mistake, this comes at a cost to everyone. Patients can’t get in with specialists. Some patients struggle to see their own physician. My friend’s spouse is perilously ill for non-coronavirus reasons, but necessary treatments have been delayed because of the complications COVID-19 places on the entire system.

Mothers who have delivered are discharged earlier than usual. Elective surgeries are canceled, as you point out. We try to get people out to make space for sick patients when they begin to arrive, minimize the exposure of already-sick patients to COVID-19, and make as many ventilators (including those used for elective surgeries) available as possible.

Communities Offer Hope Through Creative Solutions

Meanwhile, doctors are studying guidelines for how to handle situations nobody should have to face. How do you tell a sweet grandmother she’s going to die because she needs a ventilator and there aren’t any? How do you tell a man’s family he’s being taken off a ventilator to face certain death because he isn’t improving, and it’s being given to someone with a better chance of recovery? How do you guide a family through their last conversation with a beloved mother over a screen? Nobody wants these things to happen, but we must prepare for the contingency.

At the same time, the hospital and community are finding creative ways to reach out to our neighbors who suffer from chronic disease, chronic pain, mental health ailments, or just plain loneliness. A temporary transportation system has been developed to bring food to patients who are food insecure. Hospital associates are being prepared to do jobs outside their normal duties in case we find ourselves shorthanded.

Hospitals throughout the area have run short on personal protective equipment (PPE) and have had to repurpose supplies in ways they were not originally designed for. Our community has generously donated PPE. A local hotel has agreed to provide temporary housing to medical workers and first responders who feel the risk of bringing the virus home to their families is too great.

I can’t say every town is blessed with an exceptionally well-run hospital, compassionate medical staff, and supportive community the way ours is. If yours isn’t, I pray you may be spared the worst of this disease, as well as your own medical condition. But while my most ardent wish is for this plague to pass as soon as possible, I also see it bringing out the best in many people around me.

Please, Anonymous, don’t give up hope. Your suffering may be hidden, but it is not utterly invisible. And while many people suffer quietly in this calamity, numerous others are doing hidden acts of service in communities throughout the nation to bring mercy.