In the second lecture of Hillsdale College’s free online Constitution 101 course (which you can take along with me here), professor Thomas G. West analyzes America’s founding principles as spelled out in the Declaration of Independence.

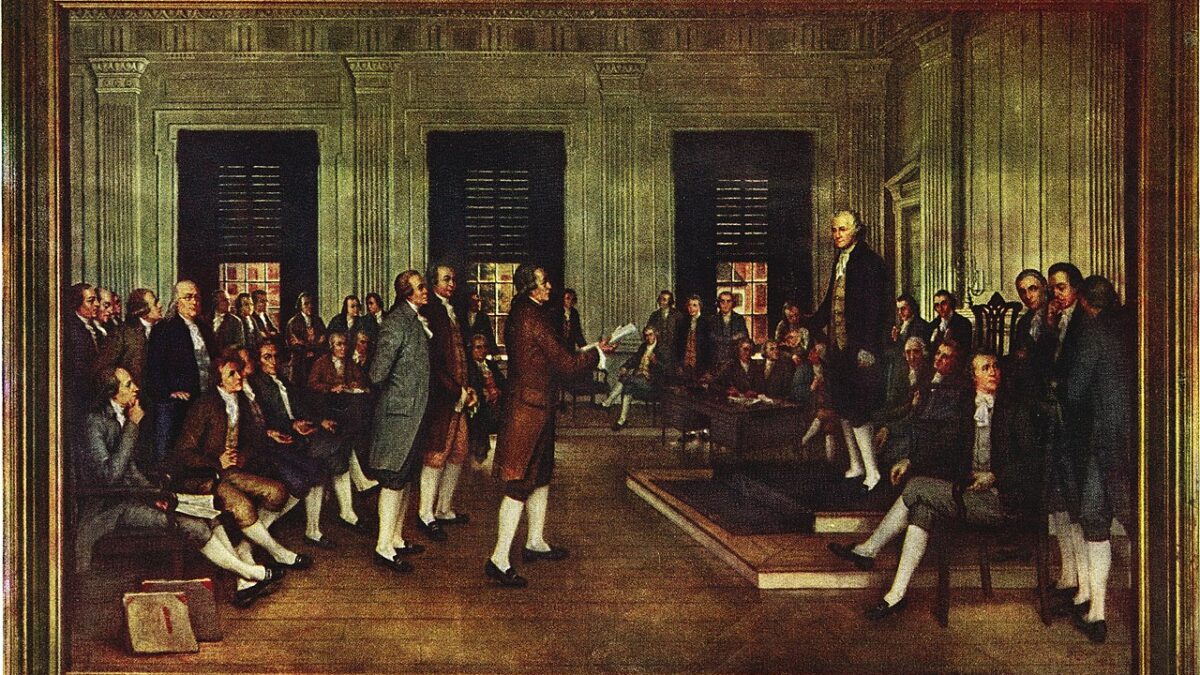

How the Declaration of Independence Happened

For decades, the longstanding agreement between the British government and the colonies was that each entity largely left one another alone. Over time, colonists grew comfortable with this isolation — that is, until the crown began to levy heavy taxes upon the colonist and demand they quarter British soldiers in their homes.

The Declaration of Independence is split into three main parts. First, it states the principles of government as spelled out in the universal laws of nature, which transcend space and time. Second, the Founders provided a list of specific grievances — each of which prove that Britain violated these universal principles. Lastly, on basis of universal principles, the Declaration draws the necessary conclusion — the colonists, whose rights were trampled upon by the crown, must now govern themselves independently.

What are America’s Founding Principles?

The Declaration states that all men are created equal, but what does that mean? And who are considered men? According to the Founders, all of mankind, including women and people of color, are created equal. No one is made legal through legislation or via government programs. It is a condition bestowed upon each one of us by a higher authority at birth. No one is born to be the slave of another.

In the state of nature — that is, where government does not exist — all men are equals. However, as Thomas Hobbes famously wrote in 17th century, life in the state of nature is nasty, brutish, and short. Thus people may submit to the authority of a leader in order to maintain order and preserve safety.

The Founders viewed the primary purposes of government to be three things: national security, criminal justice, and civil law to preserve one’s right to live without fear of death or violence and the right to own property. Each of these preserve order in a society. Today, government’s priorities are skewed, West said. As hundreds of African Americans die in Chicago each year, where killing in self defense has become a routine thing to secure one’s own safety, our government worries about whether or not someone might feel they were unfairly profiled at an airport checkpoint, he added.

The Founders also stated it is necessary to provide for the poor — a safety net of last resort if a private charity or church cannot help. They did not think inequality violated the terms of the social compact, but that starvation and destitution of people unaided by their government did.

The Modern Understanding of Liberty and Equality Is Not As Intended

Today’s understanding of equality embraces the idea that disadvantaged groups of people deserve special status in order to make up for historical oppression. This view of equality is very different from how it was intended in the the Declaration of Independence and in other founding documents. To the Founding Fathers, the right to liberty meant the right to be free from the coercive influence of others, West explains. Today, liberty means that government ought to set up access to services and goods in order to make transportation, housing, and medical care accessible for all, even for those who cannot afford them.

While a government must be strong in order to maintain order, it must constrain itself so as not to trample upon the rights of those it’s supposed to protect. Limitations on a government’s power are necessary to preserve the rights of its citizenry. These rights as spelled out in the Declaration have been misunderstood from their original meaning. While the right to life and liberty are spelled out explicitly as a right each citizen is guaranteed, happiness is not. The pursuit of happiness and the right to own property are rights all of us are born with, but the ends of those rights — happiness itself or material wealth — are not.