Donald Trump could have been a contender. Technically, there’s still a chance he’ll find a way to beat Hillary Clinton. Even if he does, he’ll preside over an incoherent mess of a party, full of factions too weak to unite against him but too strong to unite around him.

Trump had a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to change this equation and legitimize his candidacy by offering an incisive, radical reboot of Republican foreign policy. Security is the last leg standing in the three-legged stool used to depict the party’s mainline conservative platform.

The first, liberty, no longer resonates with enough Republican voters, for whom the second, prosperity, now sounds like a code word for self-enriching elites. Foreign policy was the key for Trump to reunite the GOP in his image. Instead he offered an incoherent heap of contradictory nonsense.

The result is a conceptual void at the center of the party. It’s one only one faction can fill—and will, as politics abhors a vacuum. That faction will be the one with the most internal cohesion, the best institutional support, and the hardest-earned, hardest-learned lessons about political opportunity, failure, and survival. Yes, neoconservatism is back.

It’s Reform Neoconservatism, Natch

Lest a freakout commence, we are not talking about a return of the neoconservatism of the Bush years. “The neocons” themselves, as its members were caricatured, are well aware that their strain of neoconservatism was the latest in a series of (at least) three intellectual and political permutations. So it’s only to be expected that a fresh wave would come along. The old guard has largely relinquished the torch.

Although neoconservatism certainly possesses the strength and continuity as a movement to ensure a new generation picks it up, younger neoconservatives face a unique opportunity for the kind of thing they ought to feel better prepared for than most: a careful yet bold reformation or re-theorization of how their animating principles are best translated into action that will gain purchase amid our stark challenges and uncertain future.

Critics, skeptics, and enemies abound. Anyone daring to call himself any type of neoconservative is likely to face an immediate trust gap, if not outright contempt. Nevertheless, inside the GOP and out, there is now so little alternative to reform neoconservatism that patient and thoughtful reform neoconservatives will find themselves with more of the benefit of the doubt than they might at first imagine.

Why? First, every major school of foreign policy today is weighed down by internal contradictions. Second, we are beginning to realize that these contradictions arise from our desire to conceptually master our uncertain world, whatever the price. Third, and finally, neoconservatives know just how high that price can be.

Despite the apparent unpopularity of their worldview, experience has furnished neoconservatives with the right lessons for our time about how to avoid being swept from pride and power into disadvantage and defeat. Articulated well, those lessons can turn out to be immensely popular touchstones for a foreign policy reminiscent of classical martial arts at its best: as active and tough as it is disciplined and even austere.

The Internal Contradictions of Every Foreign Policy

Let’s start with the first point. Although nowadays every critic of our foreign policy situation has at least one decent insight into why things are so broken and dissatisfying, no school of thought has managed to escape its own inner contradictions, which is why Trump’s hash of a platform doesn’t seem all that outlandish to many people.

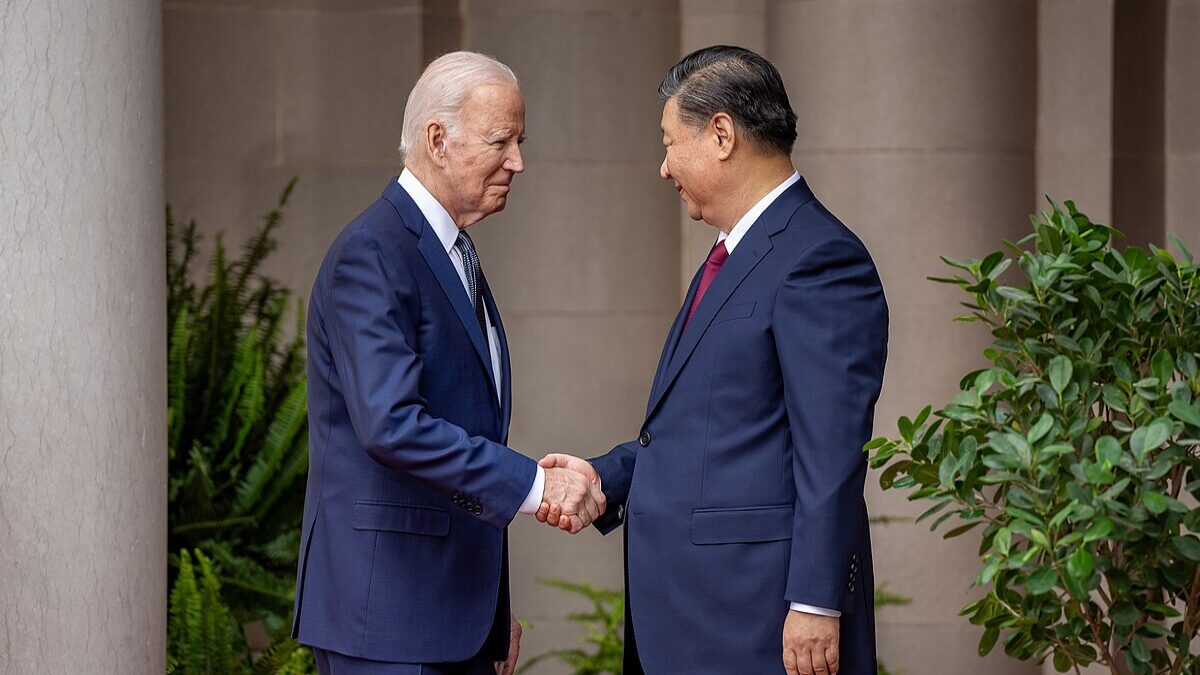

Obamaism mixes the appearance of inaction with the reality of bad action—a recipe for incoherence that’s the worst of both worlds. Clintonism, by contrast, wants to use “smart power” in a way that looks and is more muscular—but its intended payoff, a zone of peace wherein the international political economy can do the work of security, now seems as implausible as ever.

On the Right, broadly speaking, old-style Scowcroftian realism makes unrealistic judgments about the building blocks of its conceptual apparatus—who are our friends, who are our foes, and who in the gray area between we can build a modus operandi around. Neither the hawks nor the doves on the nationalist side of the spectrum Trump wants to own have a plausible argument for how to thrive in a world where the United States cedes world dominance to whichever competitors are hungry to take over.

The fact is, the United States is in an unenviable but inescapable position: we must remain, for now, the world’s master power—but we must resist the temptation to reduce the current world situation down to something we can master in our minds. The problem is not one of a failure of principle, but a breakdown of the predictable. The degree of global fluidity and uncertainty is now so high, thanks to the Obama administration’s quasi-policy, that any ambition for “solving” our foreign policy challenges has to be put to one side.

Among elites and the public alike, there is a dawning awareness of this predicament. On the one hand, we need people with a clear, coherent worldview to navigate our way; on the other, we need them to do so without succumbing to the overweening ambition and sense of grandeur that has defined nearly every significant era of American foreign policy.

We Want Safety Without Responsibility

The one important era that marks an exception is to be found at the very beginning of the Cold War. There, it was nascent “realism” that took grand, ambitious principles—at a moment of unparalleled American power—and translated them into a far-reaching policy program—containment—that was as active and tough as it was disciplined and austere.

Today, there is just not enough evidence that current “realists” have the heft required for an encore. Nor do Obamaism, Clintonism, or Trumpism appear to be up to the task. This is where, in the realm of actionable grand strategy, a reform neoconservatism can and should come in.

People well-steeped in neoconservatism know best the cost of contradictions. That Trump’s foreign policy program has not diminished his political force reminds us that many people—in general, but especially today—are enthusiastic about contradictory nonsense when it seems to break through a persistent impasse. This, in fact, is why post-9/11 neoconservatism managed to punch through the conceptual logjam of ‘90s Clintonian neoliberalism and the kinder-gentler-humbler foreign policy of the ‘90s Bush imagination.

To be sure, “the neocons” had been gearing up for many years to take charge of international relations once W. took power. But the state of play between 9/11 and the invasion of Iraq threw that diligent (some might say overzealous) planning into great disarray. Circumstances large and small conspired to turn post-9/11 neoconservatism into a more incoherent project than its architects could have hoped. The attacks of September 11 scrambled the neoconservative project much more than it appeared at the time, creating political pressure and time pressure that required neconservatives’ grand strategic plans to be rushed, compromised, and conceptually muddled.

But, ironically, it’s the muddle that made the rush possible. In the fog and panic of war, Americans wanted—and needed—a rallying point. Certainly the antiwar movement was strong and popular, but its vision could not be crystallized well enough into actionable policy.

Going to War with the Policies We Had

Progressives in that moment looked as lamely “do-nothing” as conservatives later did on the domestic front. Yet the longing for dramatic action, among elites and the public alike, meant that too few wanted to run the neoconservative playbook right, in careful sequence from start to finish. Instead, they threw neoconservative ideas haphazardly into battle.

Just as we “went to war with the army we had,” we went to war with a fast-food version of neoconservatism, messily slapped together in the heat of the moment by short-order cooks. From this standpoint, the result was predictable: disillusionment, and a profound loss of appetite for doing the hard and muddled work of geopolitical recovery.

Amid that hangover period, the Obama administration started out avoiding some big pitfalls. In its first term, for example, clawing back some breathing room on Russia and Iran was wise. But the administration contradicted itself by failing to prepare for or execute on what should have been done once that breathing room had been attained. Worse still, it completely failed to anticipate or understand the Arab Spring and its turn toward a level of chaotic violence that played right into Russian and Iranian hands.

Although Obama’s first term frustrated many a neoconservative, no neoconservative worth his or her salt—especially one who has learned from the lessons of the past decade—would have walked so blindly into the collapse of our strategic and moral position in the Mideast.

Nevertheless, there is work to do. Reform neoconservatism is an approach that is waiting to be brought into focus. Although Marco Rubio’s campaign allowed itself to traffic in some unhelpful neoconservative caricatures—railing, in the words of one slogan, that “nothing matters if we’re not safe”—while Lindsey Graham’s campaign struck a much more appropriate tone, warning against “mythical Arab armies” that would not do our work for us in the Mideast, and shaming Obama for acting far too rashly with superficial interventions—Syrian red lines and Libyan war—for someone so unwilling to follow through on them.

These lines of criticism suggest a neoconservative approach to international relations that seeks to prudently but entrepreneurially leverage American power, in accordance with broadly shared American principles, to prevent a broad collapse of global order, both inside and outside the “postindustrial” zone of the international political economy. Although reform-minded neoconservatives should certainly proceed with care, now is not the time to be timid. Trump’s audacity is just a foretaste of what alternatives await.