Retired Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn and his legal team, led by attorney Sidney Powell, received promising news Thursday from the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals. In a rare move, a three-judge panel ordered Judge Emmet Sullivan, the presiding judge in the long-running criminal case against Flynn, to respond to Powell’s petition for a writ of mandamus. In that petition, Powell asked the appellate court to order Sullivan to grant the government’s motion to dismiss the criminal charge against Flynn. While Thursday’s order does not guarantee Flynn a win, the signs are hopeful.

To understand why requires some lawsplaining, so let’s start with the background and then move to the procedural niceties in play.

On Jan. 24, 2017, just days after Donald Trump’s inauguration as our country’s 45th president, FBI agents Peter Strzok (since fired) and Joe Pientka questioned then-National Security Adviser Flynn, about Flynn’s December 2016 telephone conversations with Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak. More than 10 months later, after the appointment of Robert Mueller as special counsel and under threats from Mueller’s team to target his son, Flynn pleaded guilty on Dec. 1, 2017, to making false statements to the FBI agents in violation of Section 1001.

Following his guilty plea, Flynn cooperated extensively with the special counsel’s office. With his cooperation nearly complete, the government informed the presiding judge, Sullivan, that the case was ready to proceed to sentencing. On Dec. 18, 2018, Flynn appeared with his attorneys from the law firm Covington and Burling for sentencing.

Although the government had recommended a sentence of no prison time for Flynn, Sullivan berated Flynn and questioned whether Flynn might have even committed treason. After Sullivan suggested Flynn might see jail time if sentencing proceeded, Flynn acceded to the longtime judge’s suggestion that sentencing wait until his cooperation with the government was complete.

With Powell, the Flynn Case Took a Turn

But then in June 2019, mere weeks after the closing of the special counsel’s office and resignation of Mueller, Flynn fired his Covington and Burling lawyers and hired Powell. After requesting and receiving some delays to familiarize herself with the case file, Powell began shaking things. She filed a motion to compel and for sanctions, claiming the government had withheld material exculpatory evidence.

The lead federal prosecutor, Brandon Van Grack, a holdover from the special counsel’s office, assured the court that all material exculpatory evidence had already been provided to the defense counsel. Sullivan agreed and denied Powell’s motion to compel.

Powell would later file several additional motions, including a motion to dismiss the criminal charge against Flynn based on prosecutorial misconduct. Powell also filed two separate motions for “leave of court,” or permission from the judge for Flynn to withdraw his guilty plea.

Throughout her various motions, Powell exposed several problematic or suspicious circumstances concerning the investigation and prosecution of Flynn. For instance, Powell highlighted how the government had failed to provide the original FBI 302 interview summary. She also exposed several significant changes made to latter iterations of the 302 interview summaries, calling into question the accuracy of the summary form.

The public would later learn that Attorney General William Barr apparently shared some of Powell’s concerns because he appointed an outside U.S. attorney, Missouri-based Jeff Jensen, to conduct a review of the Flynn investigation.

In late April 2020, Powell began seeing the fruits of that investigation, when Jensen turned over documents previously withheld from Flynn’s legal team. Soon after, the public learned of these details when Powell filed the documents with the court, as supplements to her motion to dismiss the charges against Flynn based on egregious prosecutorial misconduct.

Among the material provided to Powell was an FBI closing memorandum, documenting the FBI’s Jan. 4, 2017 decision to close its investigation into Flynn for potential Russia collusion. But text messages provided to Powell revealed that the “7th Floor,” which referred to FBI leadership, had put the brakes on closing the investigation.

A second set of documents Powell received included handwritten notes by then-FBI Director Andrew McCabe and the former assistant director of the FBI Counterintelligence Division, Bill Priestap. Priestap’s handwritten notes proved devastating to those investigating Flynn. “What is our goal? Truth/admission or to get him to lie, so we can prosecute him or get him fired?” Priestap wrote.

Then in a shocking development one week later, on May 7, 2020, federal prosecutor Van Grack withdrew from the case, and the U.S. attorney filed a motion to dismiss the criminal case against Flynn. In its motion to dismiss, the D.C. U.S. attorney’s office explained that Jensen’s review had uncovered new evidence and that the Department of Justice no longer believed that Flynn’s Jan. 24, 2017 statements to the FBI agents — even if they were false — were material. The purportedly false statements were not material under Section 1001, the government explained, because there was no valid investigative purpose for questioning Flynn about his conversations with the Russian ambassador.

Judge Sullivan Kicked Off a Courtroom Circus

Sullivan did nothing for five days. But on May 12, 2020, he did the inexplicable: He entered an order stating that “at the appropriate time, the Court will enter a Scheduling Order governing the submission of any amicus curiae briefs.”

An amicus curiae, or a friend of the court, brief is prepared by a third party to assist the court in ruling, but while procedures exist for such briefs in civil cases, there is no analog in the criminal trial court context. However, that didn’t stop Sullivan from inviting outside parties to wade into the swamp, and it didn’t stop him from appointing, the next day, former federal Judge John Gleeson “as amicus curiae to present arguments in opposition to the government’s Motion to Dismiss.”

A few days later, Sullivan made clear he intended to move quickly with these outside briefs. He directed Gleeson to file a brief by June 10, 2020, and other attorneys to seek permission to file a brief by the same date. He directed the federal government and Flynn to respond by June 17, 2020, with further deadlines for follow-up responses. Sullivan set July 16, 2020, for oral arguments.

Sullivan had just opened the doors of his courtroom to a circus. Powell quickly sought to pull the tent down on the sideshow by filing on Tuesday an “emergency petition for a writ of mandamus,” with the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals.

A writ of mandamus is merely jargon for a court order that directs a lower court to act as required by law. It is not an appeal, but rather a separate proceeding which challenges a judge’s conduct.

To obtain a writ of mandamus, a party must “petition” or request a higher court to grant the writ or order. It is an “extraordinary remedy,” and is rarely granted. It is appropriate, however, when the petitioner: 1) has “no other adequate means to attain the relief he desires”; 2) “show[s] that his right to the writ is ‘clear and indisputable’”; and then 3) “the court ‘in the exercise of its discretion, must be satisfied that the writ is appropriate under the circumstances.’”

Thursday, the D.C. Circuit, which is the federal appellate court with authority over the D.C. District Court and thus Sullivan, issued an order directing Sullivan to, “within ten days,” “file a response addressing [Flynn’s] request that this court order the district judge to grant the government’s motion to dismiss filed on May 7, 2020.” The order then cited the appellate court’s recent decision in United States v. Fokker Services, which as we will see shortly proves suggestive. “The government is invited to respond in its discretion within the same ten-day period,” the order concluded.

Things Are Looking Up for Flynn

The D.C. Circuit’s order proves promising to Flynn for several reasons. First, mandamus is considered an extraordinary remedy and as such is rarely granted. Accordingly, in most cases, the appellate court will perfunctorily deny the petition. But in Flynn’s case, not only was the petition not rejected outright, but instead, with Powell’s petition pending only two days, the federal appellate court ordered Sullivan to respond on an expeditious basis.

That the court ordered Sullivan to file a response to the petition for mandamus is highly unusual and telling, and that the court directed him to submit his response in 10 days shows the court is serious. The fact that the 10-day timeframe expires before the due date Sullivan set for the amicus to file briefs in the Flynn case suggests the appellate court wants to put the brakes on those proceedings.

The citation in the D.C. Circuit’s order to the Fokker case also broadcasts the court’s concern that Sullivan improperly disregarded that circuit precedent. (District courts must follow the precedent of the appellate court within whose boundaries it falls, so for the D.C. District Court, the precedent from the D.C. Circuit constitutes “circuit precedent.”)

As I explained last week, the Fokker precedent demands the district court grant the government’s motion to dismiss the criminal charge against Flynn, because in Fokker, the court held that “decisions to dismiss pending criminal charges — no less than decisions to initiate charges and to identify which charges to bring — lie squarely within the ken of prosecutorial discretion.”

The Fokker case proves intriguing for another reason, which adds insight into Thursday’s order. In Fokker, like the Flynn case, both the government and the respective criminal defendants agreed on the issue and disagreed with the trial court’s conduct. Yet in Fokker, the court did not order the district court to respond, or even invite a response from the trial court.

Instead, in Fokker, the D.C. Circuit appointed an outside attorney to act as an amicus curiae, to defend the trial court’s decision.

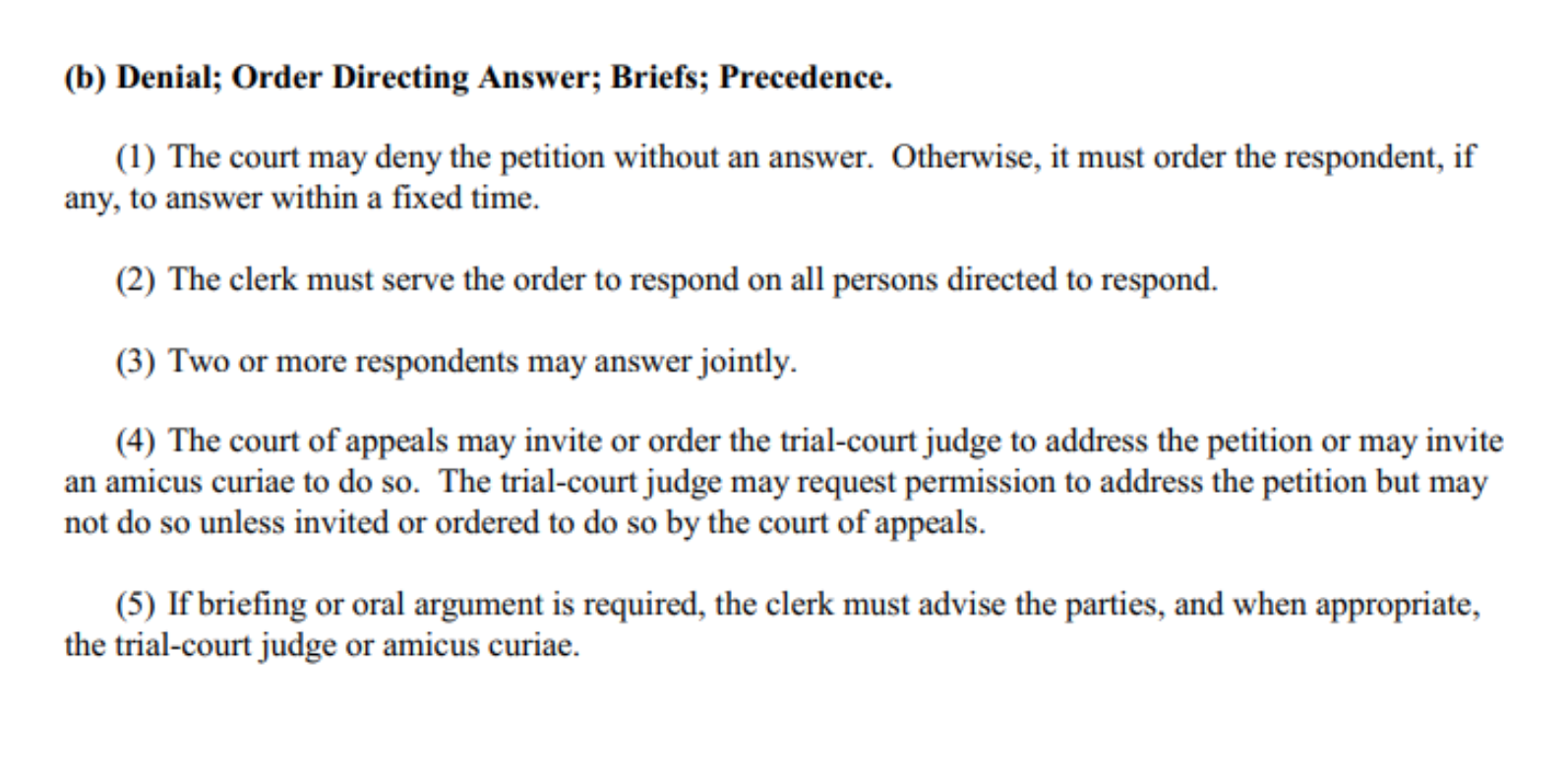

Circuit rules allow for either, stating that “the court of appeals may invite or order the trial-court judge to address the petition or may invite an amicus curiae to do so.”

The three-judge panel that issued yesterday’s order, however, didn’t want to hear from an amicus — they wanted to hear from Sullivan. Further, under the rules, the court could have merely “invited” Sullivan’s response, but instead they demanded it. That seems suggestive.

It is also suggestive that while the court demanded Sullivan respond to the petition for mandamus, it did not order the government to respond, but instead invited the Department of Justice to file a brief in its discretion. The court apparently sees no necessity in hearing additional arguments from the government.

While Fokker seems dispositive, and Thursday’s order seems to suggest the writing is on the wall, one can never fully predict how judges will rule. That is especially true when politics are in play.

Which Judges Will Decide the Case?

So, of course, the first questions that folks following the Flynn case asked were who are the judges that will decide the case and who appointed them.

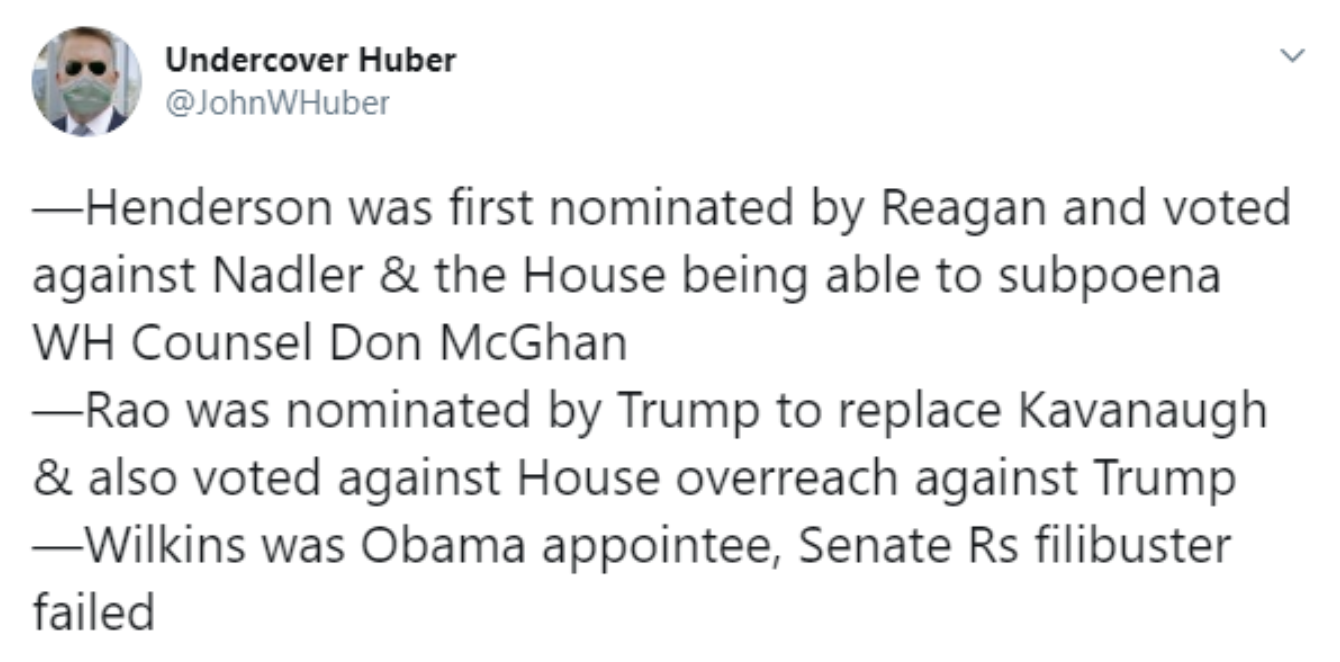

The lawyer who tweets under the moniker John Huber answered that question and more soon after the order broke. The three-judge panel consists of Karen Henderson, Robert Wilkins, and Neomi Rao. Henderson was appointed to the D.C. Circuit by President George H.W. Bush, but President Ronald Reagan had first appointed her to the federal bench at the district court level.

Rao was also a Republican appointee, with Trump nominating her to replace Kavanaugh on the D.C. Circuit. Wilkins, on the other hand, was an Obama appointee.

When it comes to politics, predictions are difficult. In this case, the D.C. Circuit has more to consider than merely the “right answer,” because Sullivan’s decision is directly at odds with the court’s decision in Fokker.

Powell agrees, telling me that Sullivan’s refusal to dismiss the charge is “in violation of clear precedent from the circuit and Supreme Court.”

“Obviously, the D.C. Circuit is taking our petition for writ of mandamus very seriously, as the court should,” Powell added.

Powell further considers the fact that the judges ordered Sullivan to respond directly — with no amicus — to be “significant.” “The handwriting is on the wall,” she told me. Powell also expects the Department of Justice to weigh in soon. After all, Powell noted, “it is the department’s motion we are defending along with the power of the executive branch.”

Powell is correct: The Department of Justice should weigh in and soon because this case is no longer just about Flynn. It is about separation of powers and the executive branch. Unfortunately, it is also now about Judge Sullivan.