In his famous 1950 Hillel House lectures, “Jerusalem and Athens,” Leo Strauss laid a vision of what he saw as a fundamental (but complimentary) tension between Jerusalem and Athens or between Scripture and philosophy. While Christian theologians might disagree with Strauss’s approach, and scholars and laymen alike might argue for a more inclusive vision of the sources of Western civilization, Strauss is at least right no note that Western civilization as we know it would be inconceivable without Greek philosophy and the Bible.

Indeed, in the contemporary attempt to cancel, modify, and, in some cases, abolish Western civilization, the classics, the Bible, and Christianity, in general, have come under assault. Thus even the critics of the West realize that “classical civilization” is one of the major pillars of the West, and in order to destroy or at least remodel the West, our classical understandings of Greece and Rome have to go.

In her new work from Princeton University Press, “Plato Goes to China: The Classics and Chinese Nationalism,” University of Chicago classics professor Shadi Bartsch explores the reality that the Chinese people have, for some time, realized the importance that classical Greek political thought has in the West and have further developed an alternating love/hate relationship with Greek thought.

Bartsch’s books derive from a series of lectures she gave at Oberlin College in 2018 and, as she admits, have stirred some controversy in China. Bartsch’s work is especially fitting for our time, seeing as how in the United States, while mainstream education is in a state of disorientation and implosion, “little platoons” of homeschooling co-ops, Christian private schools, and conservative colleges and universities are drawing from the West’s proud classical tradition and creating, in effect, a renaissance. As Bartsch notes, in its own way, China is experiencing a similar phenomenon.

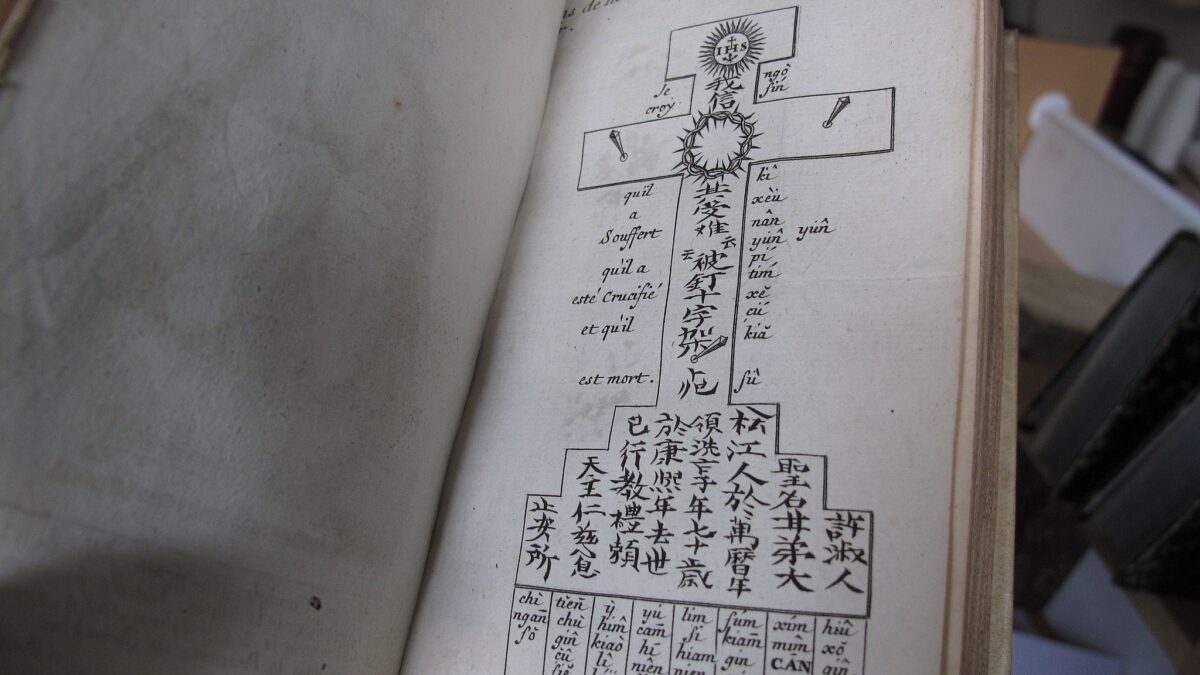

Bartsch begins her work with a discussion of the Jesuits’ famous 17th-century attempt to ingratiate themselves with Chinese intellectuals through their incorporation of Chinese thought into Christianity. As Bartsch further notes, however, the Jesuits also incorporated Greek philosophy in their evangelization of the Chinese. The Jesuits brought works such as Euclid’s “Elements” to the court of the emperor, and the Jesuit Fr. Matteo Ricci, who famously dressed as a Confucian scholar, translated the teachings of the Stoic Epictetus for Chinese consumption. Aristotle was further introduced via St. Thomas Aquinas’ “Summa Theologia.”

China’s encounter with Western thought, however, was cut short by the reoccurring view among Chinese that China was a “Celestial Empire” that had nothing to learn from outsiders; thus, the Jesuit’s efforts were largely lost.

However, interest in the Western classics returned in the late 19th and early 20th century as some Chinese intellectuals during the Qing Dynasty pushed for reform of their ancient country. The first article on Aristotle’s “Politics” in China was published in The New Citizen journal in 1898. The New Citizen was run by a Chinese expatriate living in Japan named Liang Qichao. The introduction of Aristotle’s thought helped introduce the concept of a “citizen” into a China that was used to having the notion of “subject” for those under the rule of the aristocratic class.

These new liberal ideas, rooted in the Greek classics, were met with some resistance and confusion from the Confucian intelligentsia. Nonetheless, Bartsch argues that 20th-century Chinese interest in Greek thought lasted, with some pronounced exceptions, all the way up to the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre.

After what Bartsch calls the post-Tiananmen “crackdown,” Chinese thinkers (some under coercion) began to question Western thought in general and the classics in particular. A group of Chinese thinkers published a popular article in 1992 called “Realistic Responses and Strategic Choices for China after the Disintegration of the Soviet Union.” This was a seminal text that later helped spurn the development of what Bartsch calls the “Neo-Conservatives and political Confucians,” who continue to dominate much of contemporary Chinese thought. This work argued for turning away from European Marxism and embracing traditional Chinese thought.

There are, however, some in contemporary China who argue for continued study of Western classical thought. These figures are located at institutions such as the Peking University Centre for Western Classical studies as well as classics faculty at such institutions as Fudan University and Shanghai Normal University. The scholars at these institutions are, however, largely apolitical. There is, further, a second group of thinkers in China who attempt to wed classical Greek thought with a socialist-Confucian model of the 21st-century Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

A significant number of Chinese thinkers, nonetheless, view classical thought as the source of corruption in the West or a means to critique the West — thinkers such as Eric X. Li, for example, penned a 2012 piece in The New York Times arguing that both the democracy of ancient Athens and that of the United States were allegedly limited and imperfect manifestations of democracy, which itself is an anomaly in world history.

Bartsch’s final chapter, “Thoughts for the Present,” engages in a realpolitik discussion of the projected future of U.S.-Sino relations and presents a discussion of the future of the classics in the United States. Bartsch notes the bitter irony that 21st-century Chinese intellectuals seem to have a greater appreciation for the classics than Westerners.

Moreover, Bartsch notes that China’s appropriation of, as well as attacks on, Plato and Aristotle focus on select passages of the ancient Greek thinkers’ works as opposed to a rich and nuanced vision of two of the most important thinkers in world history.

In her final chapter, Bartsch also notes that contemporary American thinkers have likewise appropriated the classics for their own purpose. Harvard Government professor Graham Allison, in his 2017 work “Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap,” argues for an inevitable conflict with China. Thucydides famously commented in “The Peloponnesian War” that “The growth of the power of Athens, and the alarm which this inspired in Sparta, made war inevitable.” Allison likewise argues that China’s rise to power will similarly collide against current American rule.

The Chinese, of course, have not responded well to this assessment, as Bartsch notes. In response to Allison’s assessment, the pseudonymous Chinese author Guo Jiping responded in the People’s Daily with an editorial arguing for cooperation as opposed to competition between China and the United States.

What is most shocking about Bartsch’s book is the reality that virtually every single Chinese thinker in the academy is laboring for a better future for China. Some of these thinkers argue that China should appropriate Western methods; other Chinese thinkers argue for sticking to a “purely” Chinese model. Regardless, they are laboring for the betterment of their nation. This observation is, by no means, to argue in support of the totalitarian measures the Chinese Communist Party uses to keep their intellectuals in line. As the recent Covid lockdowns, as well as rumblings of attempts to bring Taiwan under the CCP (not to mention a series of invasive balloon launches), reveal, China is not afraid to flex its totalitarian muscle.

Acknowledging intellectual uniformity in China, rather, is to note the tremendous contrast with the West in which the former post-Enlightenment freedom of inquiry in academia has turned into a different version of totalitarianism in which academics nearly universally argue for modification, if not the destruction of their own nations. How and if the West will be able to recover from this malaise is difficult to judge, but if we do, we will likely find at least some of the intellectual sources for a new renaissance within our classical tradition.

You can find Shadi Bartsch’s book, “Plato Goes to China: The Classics and Chinese Nationalism,” here.