On Dec. 8, federal Judge Emmet Sullivan dismissed as moot the criminal charge against Michael Flynn following President Trump’s pardon of the retired lieutenant general.

Those outraged over the vindicative and unjust targeting of President Trump’s former national security advisor by the Obama-Biden administration and then the special counsel’s office celebrated the conclusion of the case. Yet Judge Sullivan’s dismissal came in the form of a vindictive, unconstitutional advisory opinion, designed to convict Flynn of a crime he did not commit and to disparage President Trump and the Justice Department.

Flynn and the Department of Justice should not allow Sullivan’s final irrational and unhinged act of judicial defiance to go unanswered. Flynn and the Department of Justice should file a joint motion to vacate the opinion. When Judge Sullivan refuses, they should seek review by the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals. While such a procedure is rare, it is justified in this case.

A Quick Recap

The facts of the Flynn case could fill a multi-volume treatise, but simply stated, on Dec. 1, 2017, Flynn pleaded guilty to one count of making a false statement to the FBI during a Jan. 24, 2017 interview. In that interview, FBI Agents Peter Strzok and Joe Pientka questioned Trump’s then-NSA about his conversations with the Russian ambassador during Trump’s transition period.

Flynn later fired the attorneys who had represented him during the plea negotiations, hired Sidney Powell, and filed a barrage of motions, seeking undisclosed exculpatory evidence and dismissal of the charges for prosecutorial misconduct. He later sought to withdraw his guilty plea.

While these and other motions were pending, Attorney General William Barr appointed an independent U.S. attorney, Missouri-based Jeff Jensen, to review the Flynn case. Jensen’s review revealed that the special counsel’s office had withheld substantial evidence from Flynn’s attorneys, including evidence establishing the FBI had questioned Flynn without a proper investigative purpose. The evidence also indicated Flynn had not lied to the agents.

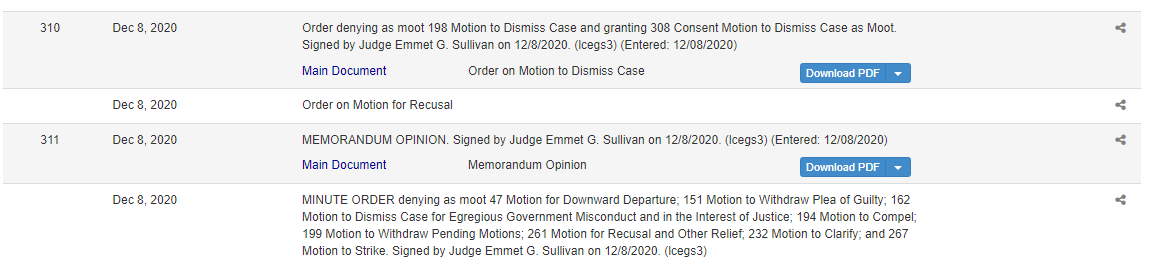

Based on this newly discovered evidence and Jensen’s recommendation, the Department of Justice concluded the case against Flynn should be dismissed. Accordingly, it filed a Motion to Dismiss with the court under governing federal procedural Rule 48(a). Rather than granting the motion, Judge Sullivan appointed an outside attorney who had a proven anti-Flynn and anti-Trump bias, retired judge John Gleeson, to serve as an “amicus curiae,” or friend of the court. Gleeson later filed what D.C. Circuit Judge Karen Henderson called an “intemperate” brief opposing dismissal of the charge.

Flynn’s attorney immediately sought mandamus, or an order, from the D.C. Circuit Court directing Judge Sullivan to dismiss the charge. In a split 2-1 decision, a panel of the D.C. Circuit originally ordered the case dismissed, but then the entire court reheard the mandamus petition and held that Flynn must await a ruling on the motion from Sullivan before the appellate court would enter the fray. The appellate court then remanded the case to Sullivan, telling him to resolve the matter “with all due dispatch.”

While the D.C. Circuit on Aug. 31, 2020, directed Judge Sullivan to act with dispatch, the Flynn case lingered until President Trump, on Nov. 25, 2020, issued Flynn a pardon. Thereafter, the government moved to dismiss the case against Flynn as moot based on the presidential pardon.

Sullivan Exceeded His Constitutional Authority

Upon receipt of the government’s motion to dismiss the case against Flynn based on the presidential pardon, Judge Sullivan had one job only: to dismiss the case. Instead, Sullivan issued a 40-plus page opinion, defaming Flynn behind the shield of judicial immunity and castigating President Trump and the Department of Justice. Sullivan did this under the guise of addressing the government’s motion to dismiss the criminal charge against Flynn under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure Rule 48(a). That analysis alone spanned more than 20 pages.

But once President Trump issued a pardon for Flynn, the government’s earlier Motion to Dismiss was moot because the court’s judgment on the Rule 48(a) motion could have no “meaningful impact on the practical positions of the parties.” Also, as the Supreme Court explained, “a court is not empowered to decide moot questions or abstract propositions, or to declare for the government of future cases, principles or rules of law which cannot affect the results as to the thing in issue in the case before it.”

Yet Judge Sullivan ignored the constitutional limits on his judicial authority and pontificated on his views on the law, Flynn, Trump, and the Department of Justice.

Transparent Gamesmanship

Not only was the government’s Motion to Dismiss based on Rule 48(a) moot, but Judge Sullivan knew it, yet intentionally—and transparently—ignored the constitutional mandate that federal judges only render decisions involving a “case or controversy.” Sullivan’s conclusion acknowledges this reality.

“[T]he application of Rule 48(a) to the facts of this case presents a close question,” Judge Sullivan wrote, before noting that the government’s motion to dismiss pursuant to Rule 48(a) is moot, “in view of the President’s decision to pardon Mr. Flynn.” That is exactly right, which is precisely why Sullivan’s order should have begun and ended with that paragraph instead of it being tacked at the end of his 40-page hit job.

But it wasn’t merely Sullivan’s opinion that exposed his gamesmanship, as Leslie McAdoo Gordon, the attorney who represented a group of federal practitioners as amicus curiae in the Flynn case, highlighted on Twitter. As McAdoo Gordon explained, Sullivan attempted to camouflage his unconstitutional advisory opinion by “making it superficially look like the opinion relates to the mootness (pardon) motion, but it does not. It’s an opinion on the Rule 48 motion, . . . [but] by putting these two motions together in one order, he obscures that distinction.”

That Judge Sullivan connived to confuse is clear, McAdoo Gordon explained, when the minute orders Sullivan issued are compared: Judge Sullivan issued a single minute order disposing of all other pending motions as moot at the same time he issued his advisory opinion on Rule 48. “The order on the Rule 48 motion should have been grouped with those” other motions as well.

Sullivan Omitted Material Facts and Wrote Falsehoods

But had Judge Sullivan followed the appropriate procedure—and the Constitution—he would not have been able to vent for 40-some pages on his personal views about Flynn, Trump, and the Department of Justice. Judge Sullivan had a lot to say, but all of it was slanted, some of it was false, and huge swaths of material facts were omitted.

For instance, “many of the government’s reasons for why it has decided to reverse course and seek dismissal in this case appear pretextual,” Judge Sullivan wrote. “Pretextual” is the legal nicety used for calling someone a liar. So, in his advisory opinion, Judge Sullivan asserted that the government appeared to be lying about why it wanted to dismiss the case against Flynn.

And the “circumstances” Judge Sullivan notes to support his view? That Flynn served as an advisor to Trump, that Trump has not hidden his interest in the case, and that, according to the anti-Trump amicus Gleeson, between March 2017 and June 2020, President Trump tweeted or retweeted about Flynn “at least 100 times.”

Sullivan also noted Powell had spoken with President Trump and asked him not to issue a pardon for her client. “And simultaneous to the President’s ‘running commentary,’” Judge Sullivan added, “many of the President’s remarks have also been viewed as suggesting a breakdown in the ‘traditional independence of the Justice Department from the President.”

But Sullivan completely ignored the appointment of an independent U.S. attorney to investigate the Flynn case and the overwhelming evidence that investigation uncovered showing that no crime had been committed. Sullivan also ignored that there was no evidence indicating Trump interfered in the Department of Justice’s decision on the Flynn case, and in fact the decision to dismiss the case came only after U.S. Attorney Jensen recommended dismissal.

While Judge Sullivan made passing mention of a few of the details Jensen uncovered, the vast majority of the troubling facts were omitted from the opinion. Those details are substantial and establish Flynn’s innocence, notwithstanding Judge Sullivan’s attempt to convict Flynn in figurative abstention.

I’ve already catalogued the evidence establishing Flynn’s innocence here, and a quick comparison to Sullivan’s opinion confirms the long-time federal judge’s hit job was shoddy.

Not only did Judge Sullivan ignore the overwhelming evidence of Flynn’s innocence, he bypassed the evidence of government (and others’) misconduct: Judge Sullivan completely ignored the strong evidence that Flynn’s prior attorneys provided ineffective assistance of counsel and acted under a non-waivable conflict of interest; he gave no mention to the prosecution’s withholding of evidence in violation of his own standing order; and the special counsel’s improper threats to target Flynn’s son went ignored.

In addition to his wholly inappropriate analysis of the Rule 48 Motion to Dismiss, Judge Sullivan also used the opinion to comment on the pardon and its consequences. “A pardon implies a ‘confession’ of guilt,” Judge Sullivan unnecessarily wrote, attempting to forever brand Flynn guilty by virtue of the pardon. This tack continued for several pages, all of it gratuitous.

Judge Sullivan Leaps the Logan Act

Beyond the slanting and lying-by-omission that blanketed Sullivan’s opinion, on at least one factual matter, the long-time federal judge was indisputably wrong: Sullivan wrongly concluded that the prosecution could prove Flynn had lied about his conversations with the Russian ambassador based on Flynn’s admission in the plea agreement to discussing sanctions with Russia. That admission—extracted after the FBI threatened Flynn’s son—however, would hold no weight because the since-declassified transcripts of Flynn’s conversation with the Russian ambassador prove Flynn never discussed sanctions on the telephone call.

As if these problems were not enough, Sullivan exposed himself as now but a shell of a once-respected jurist when he—in all seriousness—wrote that “in the final analysis, the government did not charge Mr. Flynn with violating the Logan Act.”

There was no “final analysis.” The Logan Act was the pretext. No serious person would consider this antiquated law, on which no conviction has ever stood, as a basis to investigate or charge any American, much less the incoming administration’s named national security advisor. And that Judge Sullivan found it fitting to suggest the Logan Act served as a basis for targeting Flynn shows that he is serious about one thing only—his irrational disdain for Flynn and Trump.

Pontificating on Difficult Constitutional Questions

While the D.C. Circuit court has proven itself uninterested in reining in Judge Sullivan, it may have no choice in this case because Sullivan did not merely use the bench to put his political vendetta to pen, but he announced some problematic principles of law.

The D.C. Circuit’s en banc opinion strongly suggested that a lower court’s power to deny a government’s motion to dismiss under Rule 48(a) was extremely limited. But in his advisory opinion, Judge Sullivan claimed the authority to discern whether the executive branch, “as a whole” was acting “contrary to the public interest” in dismissing criminal charges.

This assertion, and the remainder of Sullivan’s legal analysis, appears at odds with the doctrine of separation of powers. That fact might force the appellate court to act, even if Sullivan’s inappropriate public commentary might not have prompted the vacatur of his opinion.

But first, Flynn or the government or both must move to vacate the inappropriate advisory opinion, and here they have solid grounds to do so.