We’re now into our second year of theorizing about what went wrong in 2016, which is itself illustrative of the prejudice in much of political media. Most of these stories have nothing to do with Donald Trump’s policies or his behavior — topics well worth covering — and everything to do with creating the impression that the electoral process was dangerously flawed. Whether The Comey Letter swung the election or Fake News swung the election or Facebook data mining swung the election, there have been so many stories intimating that our democratic institutions have been subverted, that you sense certain people might be reluctant to accept the sanctity of the process.

I bring this up, because this week, a new Politico piece theorizes that a lack of “trusted news sources” in rural areas, rather than any particular issues, gave Donald Trump victory in 2016. It is perhaps the most unconvincing, inference-ridden, self-aggrandizing piece in the entire “What Went Wrong?” genre. The premise, basically, is that a lack of local media sources left a void that was filled by Donald Trump’s tweets and unreliable conservative sites, and that factor turned the 2016 election, “especially in states like Wisconsin, North Carolina and Pennsylvania,” where hapless Americans were unable to make educated choices without proper guidance from journalists.

“The results,” Shawn Musgrave and Matthew Nussbaum write, “show a clear correlation between low subscription rates and Trump’s success in the 2016 election, both against Hillary Clinton and when compared to Romney in 2012.” Setting aside the problem of correlational/causation and all that, every one of these stories is driven by the unstated notion that Clinton was predestined to win the 2016 election, and any other outcome means something went wrong. There’s simply no way, a year into Hillary’s presidency, that major outlets would be doing a deep dive into the viewing habits of urbanites to try and comprehend how they could have been crazy enough to elect her.

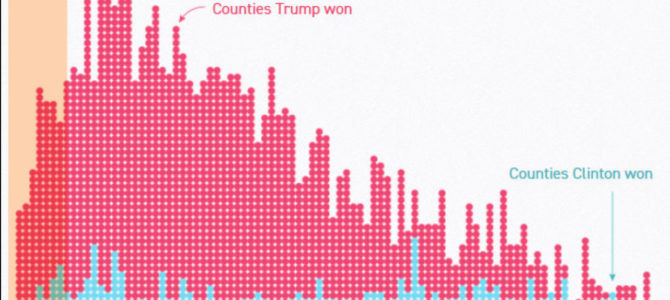

It’s true, the world is changing and also it is inarguable that places with larger populations that have the means to support local newspapers (like the scrappy New York Times) would be more inclined to vote for Clinton, while in rural areas where subscription-based outlets are more difficult to maintain, they would not not. Both these things are true. Yet, there is no data in the piece — despite nearly 4,000 words and a number of graphs to create a scientific veneer — offering any compelling evidence that the dynamics of a race would be altered if the Bedford Falls Examiner was still in business.

In the old days, we’re told, the local reliable church-going editor would run dispassionate stories from trustworthy sources.

In the days before the Internet, about a dozen news outlets dominated national political coverage. They included the major television networks, weekly news magazines, The Associated Press, and about a half-dozen newspapers. Wire services such as The New York Times News Service and The Washington Post-Los Angeles Times service sent out their articles to smaller papers across the country, guaranteeing vastly wider circulation for their stories.

For people who care about the news, larger papers and stations still exist, but they exist online. Rural Americans, like urban Americans, get most of their news online. They follow national trends in their news consumption. After decades of skewed coverage, they’ve become skeptical. But like other voters, they rarely alter their positions, and when they do seek out the news they seek our news that feeds their predominant political prejudices. You may not like that rural Republicans get their news from FOX and Sinclair rather than CNN and MSNBC, but that’s a matter of ideological taste.

It is almost also certainly true that Trump’s “relentless use of social media” had something to do with perceptions of his voters (his obsession with Hillary is another story.) But would his successful application of new media, once celebrated when the appropriate people won elections, been any less effective because there was a Washington Post wire story running in the local paper? Would Trump voters have traded in the MAGA hat for an “I’m with her” bumper sticker if they read Paul Krugman in their paper? This seems unlikely.

What’s far more plausible is that a combination of factors made Trump in 2016 a marginally more agreeable Republican candidate to rural voters than Mitt Romney in 2012. Or, perhaps, even more relevant, that Hillary Clinton was far less likeable, and had far less political acumen, than the candidate Romney faced in 2012, Barack Obama. But even without factoring in the personalities, comparing turnout and voting patterns in different years in the way Politico does is fraught with other problems. Americans are fickle, and national events, trends, local economic factors, and thousands of other variables can alter results, as well.

The idea that a lack of a local newspaper is a determinative factor in swinging enough people to turn a national election is probably a reflection of journalism’s self-importance and an inability to live with the idea that Americans could vote for Trump without being hoodwinked in some way. Because, let’s face it, Democrats never really lose an election, do they? If the Supreme Court isn’t stealing the presidency then propaganda outfits are weaponizing social media mindbots to control your vote or the Constitution is getting in the way of proper “democracy.” We’re going to keep doing this until Americans make the right choice.