Reading books about economics can be tedious, but when a sharp analysis of a prominent debate becomes available, that’s enough to pique my sustained interest. Equal Is Unfair: America’s Misguided Fight Against Income Inequality is the kind of analysis that pulls back the curtain on one of today’s most contentious topics, and as such, should interest many others. President of the Ayn Rand Institute Yaron Brook and fellow Don Watkins work methodically to refute the mainstream notion that income inequality is one of the greatest threats facing American society.

Their opening salvo is grounded in a truth that those concerned about income inequality are working hard to obscure: “The reason Americans have never cared about economic inequality is precisely because they recognized that it was the inevitable by-product of an opportunity-rich society.” I suspect that the vast majority of Americans still don’t really have a problem with rocket scientists earning more money than cashiers or with superstar basketball players raking in more pay than professors.

Equal Is Unfair is really a critique of the misleading nature of the income inequality debate, which plays on people’s emotions and economic angst. Watkins and Brook make good use of history, statistical data, and economic theory to dispel the notion that economic mobility is no longer possible in America.

Unfixing the Pie

The book sets out to explain what it means to live in a free society. And it quickly stakes the claim that a free society places demands upon individuals—to think and produce, to be self-supporting, and to make the most out of their own advantages, as well as overcome challenges.

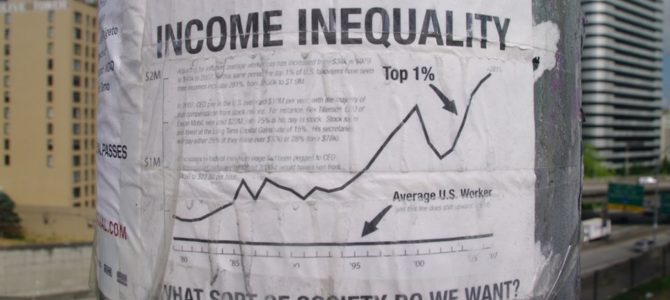

So what is income inequality? According to Equal Is Unfair, the catchphrase is rarely spelled out by pundits or the media, but it has a lot to do with the idea that middle class incomes have stagnated over the last thirty or forty years while the rich have seen an enormous increase in wealth. The solution invariably offered is to increase taxation on the 1 percent.

Before going on to critique the oversimplifications in some of the leading studies on income inequality, Watkins and Brook dismantle the argument that income inequality is somehow unjust by questioning the “fixed-pie” and “group-pie” assumptions. The fixed-pie narrative assumes that one person gains wealth at the expense of another; when, in fact, the wealth pie expands as more wealth is created. The group-pie narrative wrongly assumes that all wealth belongs to the nation and that it should be distributed by society evenly.

The book uses a hypothetical based on the novel Robinson Crusoe to illustrate the point: “If Robinson Crusoe and Friday are on an island, and Crusoe grows seven pumpkins and Friday grows three pumpkins, Crusoe hasn’t grabbed a bigger piece of (pumpkin?) pie. He has simply created more wealth than Friday, leaving Friday no worse off. It is dishonest to say Crusoe has taken 70 percent of the island’s wealth.”

Logically, this bit of reasoning would satisfy many people, but proponents of income inequality have unleashed compelling data points. IRS tax data shows that from 1979 to 2007, the top 1 percent saw 60 percent of income growth while the bottom 90 percent saw only 5 percent.

Watkins and Brook adeptly make the case that aggregate data points like this ignore the fact that people aren’t stagnant and that the composition of groups at the bottom changes. People may start out working poor and then move to working class, then to lower middle class and so on. Household composition also matters tremendously relative to data, when we see marriages form and dissolve and birthrates increase or taper off. The reality is that since World War II Americans have never been stagnant, nor have they stopped climbing the economic ladder.

The Guardian of Opportunity

Equal Is Unfair excels because it starts a timely—and necessary—conversation about how the American free market system works. In the era of the Fight for $15, free trade fearmongering, and ire over CEO pay, many people lack a clear understanding—the kind I never got in microeconomics class—of how entrepreneurship and American capitalism fuels progress.

According to Watkins and Brook, the foundation of our system is voluntary trade—what they describe as “the guardian of opportunity.” For example, if you purchase an iPhone from Apple or another company, that’s voluntary trade. You can choose to trade with Walmart or Amazon or some enterprising individual on Fiverr.com. The power of trade lies in being able to “offer your resources in exchange for the resources of others.”

When it comes to corporations like Walmart, it’s fashionable and convenient to peg the whole lot as Gordon Gecko-esque, greed-is-good entities. Hollywood has played no small part in shaping negative perceptions about business. In contrast, shows like Undercover Boss and recent books from CEOs like Bob Chapman and John Mackey attempt to paint a friendlier, more humane picture of entrepreneurship and business. Either way, everyone seems to have forgotten Milton Friedman’s claim that businesses have no social responsibility.

Watkins and Brook suggest that businesses can only make offers to consumers. Unlike government, they have no power to deprive people or force anyone to purchase anything. They not only have to produce things that add value to society but also compete with other businesses for consumer dollars and for the best employees by offering competitive pay.

They also must to continue to innovate or cease to exist. Put another way, the free market determines their worth. No entrepreneur or corporation can “earn a fortune without creating tremendous values that, by necessity, improve the lives of countless other people.” This is why we should celebrate innovation.

The Currency of Ideas

Chapter four of Equal Is Unfair reminds us that every worker plays a part in creating wealth. We do our respective jobs, we provide a certain amount of value to our industries, and we produce the goods and services from which we all benefit.

There are differences, however, in productivity. By naming innovators and inventors like Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla, Steve Wozniak, and Elon Musk, the authors remind us that not all work is equally productive. This sort of calculation is made by specific industries and the broader free market, but it doesn’t mean that someone’s job, regardless of pay, isn’t crucial to the economy.

It’s also from this list of innovators that Watkins and Brook are able to highlight the most valuable currency the world has known since the industrial revolution: ideas. One main theme throughout the book is that “the production of wealth is fundamentally an intellectual project.”

Talking about the value of world-changing ideas moves us away from fallacies like income inequality to the reality that the opportunity to pursue intellectual endeavors is wide open. While incomes are unequal in a free market system, anyone can develop his or her ideas to a point where they produce greater value for industry and society as a whole.

Success Depends on Effort

The narrative suggesting there are victims of income inequality is an insidious one. Equal Is Unfair does a good job distinguishing between the most vulnerable in our society, who are very disabled and must be cared for, and everyone else. Meanwhile, the victim narrative projects helplessness onto capable, low-income workers. Some Americans find it difficult to accept that the responsibility to succeed economically is on the shoulders of the individual, even when born into inauspicious circumstances.

As someone who, like many Americans, has changed income brackets several times, I think the most potent lines from the book are centered on poverty: “Poverty is not a distribution problem—it’s a production problem. People are poor, in the end, because they have not created enough wealth to make themselves prosperous.”

This may sound cold, but the economic hardships faced by millions of Americans aren’t lost on the authors. Even as they acknowledge that the struggle will be harder for some and that America hasn’t always lived up to its founding ideals with minorities in particular, they cite individual effort as the only way to actually escape poverty. And they courageously call out “one of the most troubling strains in the economic inequality critique: the implicit, and sometimes explicit, suggestion that Americans can’t succeed through their own effort.

Referencing Dirty Jobs and No Shame in My Game (a study of the working poor in inner-cities), Watkins and Brook argue convincingly that individual effort has to be connected to the dignity of work. The point here is that people should respect low-paying jobs especially, because they act as vital stepping stones for those who often have to overcome the setbacks of poverty and poor education.

This was the most difficult perspective in the book to grapple with. I conceded the point, eventually, but I also think that individual effort among the working poor would be best spent restoring the dignity of education first, even when quality schools are unavailable.

The Real Threats

Perhaps one of the smartest moves Equal Is Unfair makes is in identifying what the real threats to mobility are, especially for the less affluent: taxation, expensive licensing requirements (for things like hair braiding or being a sidewalk vendor), low quality education, cost-prohibitive tuition, and a welfare system that disincentivizes work. There’s also the scourge of political inequality where the real system-rigging and quid pro quo take place daily, courtesy of cronyism.

The theme should be obvious; the more “arbitrary power” the government claims over our lives, the more the well-connected will game the system. And it’s ludicrous to think that either more laws or the right kind of political oversight will end this corruption.

You only have to read a couple chapters in Equal Is Unfair to get the sense that the authors believe individuals should be free to be self-supporting and self-directing. This is what leads to the innovation and progress. Accordingly, Watkins and Brook lament the international scene in places like Cuba where communism holds sway and individual liberty is devalued, and Cambodia, during the 1970s, where an attempt to implement an egalitarian economic equality left as many as two million people dead.

Ultimately, Equal Is Unfair exposes political egalitarianism as intent on leveling all Americans downward and increasing government control. In their own right, Watkins and Brook call for the abolition of corporate welfare, an end to the government monopoly on schools, and the removal of regulatory barriers that compromise entrepreneurship.

By the end of the book, they have not only succeeded in extolling individual effort, but in freeing readers’ minds to consider the possibilities of free markets.