Several weeks ago, James Grant, the founder and editor of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, graced the cover of Time magazine. Here, Grant aptly warned that the United States faces perpetual low growth and an eventual dollar crisis, bringing runaway inflation, due to our crushing national debt—unless the size of government is dramatically reduced.

Naturally, the Left had a conniption. Writing for Vox, with the link to an article titled “The Smug Style of American Liberalism” in view, illustrious financial mind Matt Yglesias decided that “Time magazine decided to troll economically literate Americans this week with an alarmist cover story about the national debt.”

At Slate, Jordan Weissmann echoed Yglesias, with “Time Magazine’s new cover story is every bad conservative argument about the national debt wrapped into one.” Weissmann accompanied his article with one of his very own mean-tweets, just to show how stupid Grant is and how smart Weissmann is:

Keep in mind that Grant is highly respected on Wall Street, even among those who disagree with him ideologically. For example, Grant warned investors about Valeant long before the pharmaceutical company lost a staggering $80 billion in market capitalization in less than a year. I’m sure Weissmann saw that coming, too.

The Left’s Bad Arguments On Debt and Deficits

Weissmann, Yglesias, and company made four main arguments in response to Grant. First, that each American doesn’t own almost $43,000, because we tax the rich more than the poor, and we can also print money. The ability to print dollars is why we won’t end up like Greece. Second, Grant says America is insolvent, yet the government owns lots of assets, like aircraft carriers and roads, so it is not insolvent. Third, demand is high for government debt (U.S. Treasurys), and that means government can borrow cheaply, and spend the money on great things like roads and bridges, which will grow the economy. Reducing federal spending will shrink the economy, making the debt burden worse. Fourth, it doesn’t matter how much we owe as long as we can make interest payments. Weissmann says:

Currently, interest on the debt only takes up about 6 percent of the federal budget. As a percentage of GDP, it is lower than any time since the 1970s. In the future, we will only have to pay down enough debt to make sure our interest payments remain sustainable, as they are today. We will never have to eliminate the whole balance. Doing so would be stunningly foolish anyway. For one, markets would go crazy. The entire financial world runs on Treasury bonds—they are the gold standard of safe assets, and are essentially treated as the next closest thing to cash. Paying them all off would suck the blood out of the world’s financial circulatory system.

These arguments show how little Yglesias and Weissmann understand the point Grant’s article is making, or the state of the financial markets. Let’s respond in order.

The Poor Always Suffer Most from Funny Money

The poor will end up paying more than the rich in terms of quality of life and standard of living. They already have. As prices of food, rent, education, and health care skyrocket, real wages for many are flat. Real wages are flat because of the Fed’s “money printing” (more on this at the end of the article). The rich, meanwhile, own a lot of assets that go up disproportionately when the Fed artificially lowers rates and prints money. They are not only fine, they’ve never been better.

Printing dollars and running deficits will not lead to dangerous levels of inflation, measured by the Consumer Price Index, as long as the U.S. dollar remains the world’s reserve currency (as long as the dollar has buying power abroad). This can’t last forever. The more irresponsible we are, the closer we get to the end of “king dollar.” Does anybody know when this will happen? Of course not. But if we continue our current course it will happen. This is what Grant is warning us about.

Assets Matter Only If You Can Sell Them

Assets only make one solvent if they are liquid (if they can be sold, not at a steep discount). Aircraft carriers or the national highway system will never be on the block. Further, Grant speaks of not only our current debt, but our unfunded liabilities. Unfunded liabilities represent the money the government has promised to spend, going forward in perpetuity, versus the money the U.S. Treasury is expected to take in, going forward in perpetuity. Depending on the estimate, unfunded liabilities easily total more than $100 trillion. Moody’s estimates unfunded liabilities to be 75 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) for Social Security, 18 percent of GDP for Medicare, 20 percent for federal employee pensions, and 20 percent of GDP for state and local government pensions.

Government Is Buying Its Own Debt

There’s a big demand for government debt, but it comes from the government, not the private sector. Over the last seven years, the Federal Reserve, as a result of the aforementioned “money printing,” has accumulated around $2.5 trillion in U.S. Treasurys. Low rates and the weak dollar, a result of the Fed’s policies, have caused further demand for Treasurys from foreign central banks due to their efforts to peg their currencies to the dollar and induce export-oriented growth. The Fed’s price controls on interest rates, setting them below the market rate, also cause excessive demand for debt, generally.

Furthermore, much of the demand for government debt found in the private sector is due to government regulations, like the new “liquidity coverage ratio” (LCR) rules, which you can be very sure Weissmann and Yglesias know nothing about. Weissmann and Yglesias would probably instantly love these rules, but this is the same type of regulation—where government, not business, determines what is “risky” and what is not—that induced U.S. financial institutions to hold lots of “AAA rated” MBS (mortgage backed securities) before the housing bust.

Government Spending Slows, Not Expands, Economic Growth

Next, let’s deal with the fallacy—even widely held on Wall Street even—that increased government spending causes sustainable growth. Increasing federal spending as a share of GDP actually cannibalizes the finite amount of resources within the American economy at the expense of the private sector, where those resources would be used to boost wages and living standards.

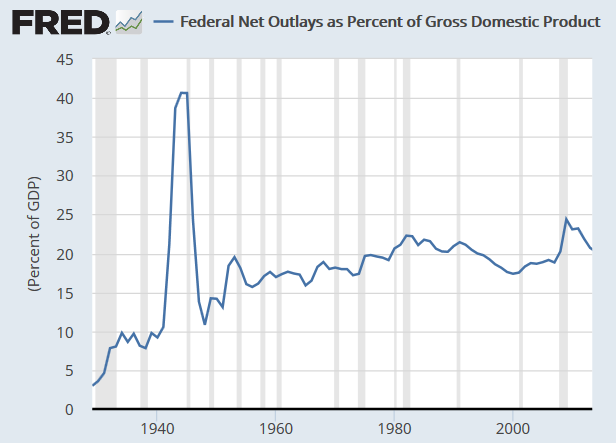

The prime example is after World War II, where federal spending fell from around 45 percent of GDP, to under 10 percent, almost overnight. Keynesians predicted another Great Depression. Rather, a very short recession was followed by economic boom, as resources were reallocated to their most productive uses that best aligned with consumer preferences.

Keynesians like to peddle the fiction the war-driven large boost in spending finally moved us out of depression. Actually, it was a large boost in private savings that led us out of the depression, as combined household and business debt dropped from 150 percent of GDP on the eve of war to 60 percent of GDP by the time the war ended. Keep in mind, the recovery didn’t take off until after government spending was downsized. During this recovery, heavy war-time taxes were largely kept in place, and the U.S. federal budget deficit turned into a surplus until the Korean War.

Another fiction Keynesians peddle, while we are on the subject, is that if stimulus doesn’t work, it is because the stimulus wasn’t big enough. In other words, you can never prove these people wrong. Aside from the logical train wreck, this kind of thinking leads ideologues to look at, say, Japan, and determine that after decades of monetary stimulus—to the point where the Bank of Japan now owns the vast majority of Japanese government bonds and more than half of Japanese exchange traded funds, and is one of the top-ten owners of most companies in the Nikkei 225 stock-index—and fiscal stimulus, meaning running massive deficits so Japan’s public debt has reached almost 250 percent of GDP, not enough is being done (we’re looking at you, Paul Krugman). More reasonable people can look at Japan, Inc. and see where neo-Keynesianism has fallen short.

While history provides many examples where reductions in government consumption induced a short recession followed by large gains in prosperity, examples abound where increased government consumption leads to a short term high followed by a terrible hangover. Just look at Brazil, Venezuela, and Argentina.

For Debt, Size Matters

Weissmann’s waxing on “Treasurys as the lifeblood of the financial system” and how “debt is only a problem if you can’t pay the interest” is especially annoying. First, everybody, including Grant, is okay with the government selling Treasurys. Even if the U.S. ran a budget surplus, the Treasury would still be selling Treasury bills (short-term government debt, the real lifeblood of the financial system) to meet day-to-day funding needs, although the supply of Treasury bonds (long-term government debt) would begin to shrink. But so what. Investors would buy private-sector debt instead, and the cost of funding for businesses would go down.

More important, what’s “stunningly foolish” is to point out that interest payments on the debt are at all-time lows due to the Fed’s near-zero fed funds rate, and assume that this can continue much longer. As mentioned above, it’s even more foolish to assume that if ultra-low rates do continue a little longer, such a development is good for the economy. Low rates are what ails us. Even in Keynes-land, low rates five years from now mean growth is still flat.

What if inflation finally ticks up after all the Fed’s easy money, due to the dollar’s substantial weakening in the foreign-exchange market? Even if rates go back to where they were in the 1990s and 2000s, the interest costs of the national debt would skyrocket, doubling our current budget deficit (the amount of money we spend more than we take in during a fiscal year) from half a trillion dollars to over $1 trillion. If the Fed had to fight stagflation, as in the ‘70s, it would face the choice of either bankrupting the U.S. government or wrecking the dollar (it would probably end up doing both in such a scenario, which is the dollar-crisis Grant is warning about).

Even under White House estimates, the interest on the debt exceeds defense spending and non-defense discretionary spending by 2021 and 2022, respectively. Sure, the White House assumes rising rates, but also increased economic growth. If rates don’t rise, neither will growth. Also, our deficit is only “down” to $550 billion in 2016 precisely because we are at the peak of a bubble. Growth isn’t going up; it’s about to fall, and bad. When the bubble bursts, the deficit will get much worse, interest costs aside.

The ‘Progressive Death-Spiral’ and Donald Trump

It is one thing to disagree about what the government should spend money on, and whether running deficits during a downturn stimulates demand. It is another thing to make stupid, snarky remarks about a guy who is well-respected by just about anybody that knows anything, and pretend the $19 trillion-plus national debt doesn’t matter.

But we can expect that, right? Even more depressing is the GOP’s consistent willingness to jump on the debt and deficit bandwagon. The Bush-Cheney deficits were bad. It is then stunning that many GOP rank-and-file, who think they’re getting something new in Donald Trump, are opting for Bushonomics on steroids.

In an interview with Fortune magazine, Trump praised the Fed’s manipulation of interest rates, and backtracked from comments suggesting he’d aggressively pay down the debt:

Fortune: You’ve said you plan to pay off the country’s debt in 10 years. How’s that possible?

Trump: No, I didn’t say 10 years. First of all, with low interest rates, you can think in terms of refinancings, and get it down. I believe you can do certain things to pay off the debt more quickly. The most important thing is to make sure the economy stays strong. You can do it in smaller chunks. You can do it in larger chunks. And you can do it in refinancings.

Fortune: How much of the debt could you pay off in 10 years?

Trump: You could pay off a percentage of it.

Fortune: What percentage?

Trump: It depends on how aggressive you want to be. I’d rather not be so aggressive. Don’t forget: We have to rebuild the infrastructure of our country. We have to rebuild our military, which is being decimated by bad decisions. We have to do a lot of things. We have to reduce our debt, and the best thing we have going now is that interest rates are so low that lots of good things can be done that aren’t being done, amazingly.

In fairness, Trump went on to make some decent comments to acknowledge that low rates do hurt savers, which is “unfair.” He also outlined the “frightening” scenario where higher rates trigger much higher interest cost for the U.S. government.

All this is worrying. Narayana Kocherlakota, a mega-dove writing for Bloomberg View, praised Trump for starting to make “economic sense” by wanting to combine fiscal and monetary stimulus. Kocherlakota mentioned that Trump’s economic plan sounded a lot like Abenomics in Japan. He failed to mention that Abenomics has failed miserably.

Trump may yet cut the government down to size, but this is unlikely. For one, the U.S. Treasury has already “refinanced” the debt. Spending is the problem. New military and infrastructure spending, plus promising not to touch entitlements—60 percent of the federal budget and rising—equals increased deficit spending. Aside from an infrastructure stimulus’ inevitable waste and big handout to unions due to prevailing wage laws, spending on any one of these things isn’t bad per se. But altogether any new spending further necessitates continued manipulation of rates and the dollar by the Fed, which means robust economic growth will remain elusive.

Trump Actually Loves Currency Manipulation

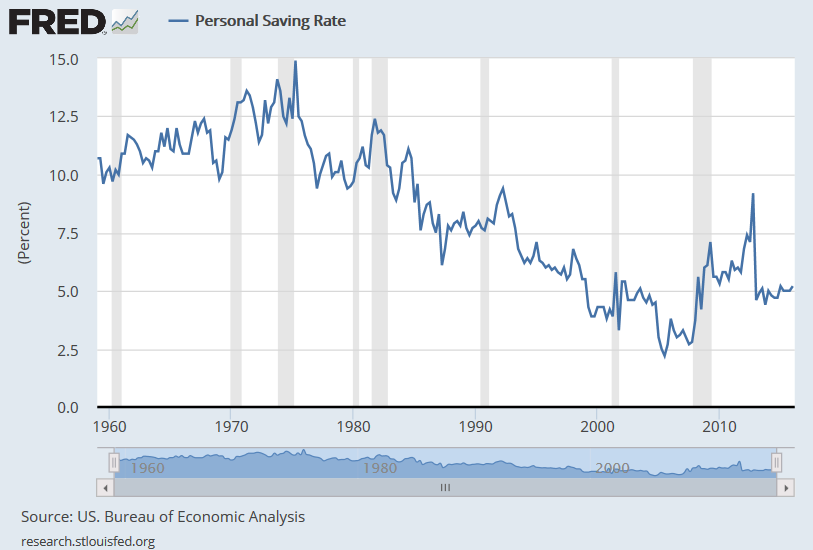

Why is the Fed’s manipulation of rates bad? For the last 30 years, the Fed’s price controls have depressed the household savings rate, and increased household debt, reducing long-term demand. The trade deficit Trump derides is, at least partly, a result of this overconsumption, and it in turn fuels more overconsumption as American dollars flowing abroad are transformed into a “global savings glut,” which further increases the appeal of debt-financed demand.

Demand being pulled forward into the present and low household savings, along with instable global dollar flows, increases the prospect of aggregate price-level instability in the future, as a recession resulting from the Fed’s earlier manipulations naturally brings some deflation (too many houses or widgets were produced, and prices drop). Once a slowdown hits, the Fed has, unsurprisingly, succeeded (several times) in exacerbating the natural deflationary process by doing things like hoarding gold (Great Depression), pouring money on favored financial firms, not following the Bagehot Rule, and paying interest on reserves (IOR), all of which served to dry up interbank lending or money velocity, reducing the money supply.

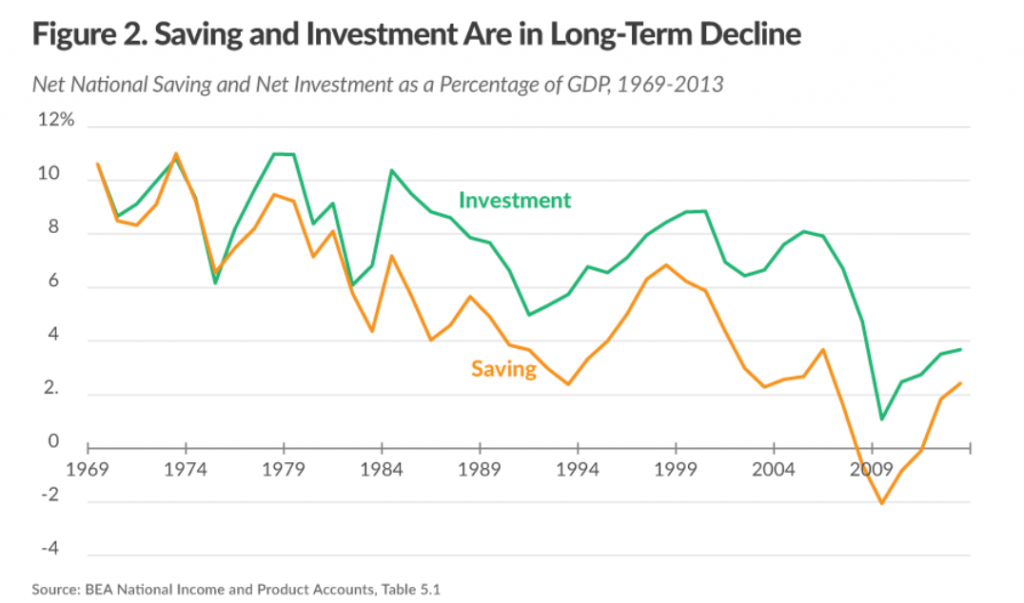

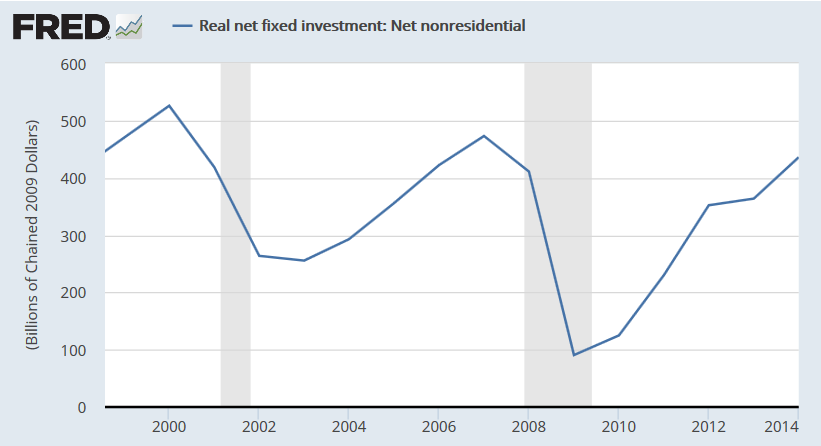

The reduction in long-term demand has made business reluctant to make long-term investments, which has hurt productivity growth, which then suppresses wages. Long-term investment is traded for short-term investment or no investment at all. Instead of putting money into projects that will add workers and grow wages, corporations have been using cheap debt to buy back their stock, or they just sit on mountains of cash. Bad monetary policy has turned should-be savers, consumers, into debtors and should-be spenders and investors, corporations, into savers.

Big Government Is Eating Our Economy

Overconsumption and low capital investment means the capital stock, or productive capacity, of the United States, measured by the existing capital structure plus capital investment minus depreciation is in decline. The biggest overconsumer of all is government. In other words, Washington is slowly consuming and destroying the wealth of the United States of America.

In areas where productive capacity is declining or flat, wages are flat. Worse, areas hardest hit are areas of the economy that require more long-term investment relative to others, and typically employ more blue-collar workers. As an aside (and this is a big debate right now), the reason median wage growth has lagged median productivity growth over the last several decades is because in certain industries, industries more dependent on longer-term capital investment, productivity growth has been flat. In other words, Trump is right to worry about the plight of blue-collar America, but his proposed solutions will make the problem worse.

Conservatives often deride the “progressive death spiral,” where government creates a problem and self-serving politicians propose more government to fix the problem that government created. It is depressing that the Republican frontrunner seems ready to further the death spiral, just as did the GOP establishment that the frontrunner’s supporters so often deride.

While the republic continues to go down the tubes, at least it will be entertaining to watch the Hannities, Limbaughs, and Drudges of the world, who lambasted the near-trillion-dollar Obama stimulus, justify the trillion-and-a-half-dollar Trump infrastructure stimulus. More light rails, bike paths, and bridges to nowhere. Get ready for some “yuge” government waste.