The War on Christmas starts earlier and earlier each year, doesn’t it! Here we are, just a few days into November, and already we’re battling over who is the least offended by Starbucks’ supposedly even-less-religious-than-normal holiday cup. On the one side you have people making fun of Christians for supposedly being offended by Starbuck’s very-not-religious cup. On the other, you have Christians denying that they are, in fact, upset.

I guess 2015 won’t go down as a particularly coherent year in the War on Christmas skirmishes.

For those of you who are confused, here’s a quick explanation of where things stand. On November 5, Raheem Kassam of Breitbart London wrote a pretty tongue-in-cheek report on the new “This is really not a Christmas cup but sort of vaguely holiday-themed” to-go cup from Starbucks. You can tell it was not the most earnest of jeremiads because of lines such as:

And behold, Starbucks did conceive and bear a red cup, and called his name blasphemy.

and

Frankly, the only thing that can redeem them from this whitewashing of Christmas is to print Bible verses on their cups next year. Not that I’d buy their burnt coffee anyway. And certainly not while they keep spelling my name ‘Ragih’ (right) on their cups.

I thought it was a totally fine piece that poked fun at the cup for being even more bland than normal, but I noticed that some of the more liberal Christians (names hidden to protect those of us who tweet impulsively) I follow were immediately aghast at this Breitbart piece, on the assumption it was meant to launch a serious War on Christmas battle.

Then some Christian shock jock type ran with it and made a video, and a set of hashtags, and Facebook links to his ad-supported web page. This, I think, is what produced not just the Christian response of “No, really, we don’t care” but the many articles claiming that Christians were freaked out by Starbucks cups. Not sure which response was first, to be honest, or if they all occurred at the same time.

WHAT PEOPLE??? NOBODY CARES ABOUT THIS YOUR EVIDENCE IS LIKE 4 TWEETS AND ONE OF THEM IS FROM A PARODY ACCOUNT https://t.co/fB1kq3WohQ

a shrill of hope (@theshrillest) November 9, 2015

New York Times TV critic James Poniewozik joked, in response to the tweet above, that we need “a snopes.com, but for whether any actual human is outraged over a reported ‘outrage.'”

This is where the story gets particularly sad, because Snopes.com is in part responsible for the faux-rage over the Starbucks claim. The site declared “false” the claim that “The coffee chain Starbucks removed all mentions of Christmas from their red holiday cups because ‘they hate Jesus.'” It cited this shock-jock video and the Breitbart London story.

I’m unable to transcribe the cry of anguish my heart is uttering over the stupidity of all this. I get that it’s fun to feel outraged, at times, but maybe all day, every day is a bit much, you know? When you have to invent some public outcry to be outraged over, you’re probably taking things too far.

If you want to have an actual discussion about the War on Christmas, a battle that has actually been raging for thousands of years and was not invented, as “The Daily Show” probably told you, by Fox News, let’s do it. But let’s not be complete idiots about it.

No, really. Let’s discuss it.

Every year we see battles over Christmas and whether it’s under siege. These battles usually take place in the public square or the market. Should town squares have Christmas trees? What about malls? Should they be renamed holiday trees? Unnamed “holy days” are less offensive than the specific holy day we all know we’re marking, right? Can government school students sing carols and not have their choir instructor sued into financial ruin? Or is it better to stick with such choral classics as “Dreidel, Dreidel, Dreidel” and “I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus” or whatever is less offensive than a Bach Christmas cantata?

Stories about the battles are easy to write. When the two sides are politically correct bullies and supposedly pious protesters who have nothing better to complain about, it’s easier still to simply root for casualties. But what if we didn’t just respond to shock jocks trolling for traffic and revenue-generating clicks and instead thought through the tension between commercialization and sacralization of holy days?

I wrote about this a bit years ago for the Los Angeles Times, but Christmas wars aren’t new. They’re ancient. Even in this country they go way back. Mayflower Pilgrims and Massachusetts Bay Colonists didn’t celebrate Christmas—Massachusetts even banned its celebration for a few decades—while others enjoyed it as a day of respite and revelry. Pennsylvania Quakers scorned the day as much as Puritans did.

The Many-Yeared Christmas Battle Saga

Various language and denominational barriers pretty much kept Christmas a private celebration. But in the early nineteenth century, some Americans began calling for a greater celebration of Christmas. By 1860, only 16 states had legalized Christmas as a holiday. It took another ten years for the U.S. Congress to do the same—although Christmas had been widely celebrated since 1830.

The American Santa Claus was also a big problem, as many religious types presciently worried it would overtake the religious purpose of the day. “This Santa Claus folly has infected family life, literature, church services, everything almost, at this season,” wrote “Germanicus” for the Lutheran Observer in 1883.

The Baptist Teacher editorialized in 1875, “We believe in Christmas — not as a holy day but as a holiday . . . Stripped as it ought to be, of all pretensions of religious sanctity and simply regarded as a social and domestic institution — an occasion of housewarming, and heart-warming and innocent festivity — we welcome its coming with a hearty ‘All Hail.’” If The New York Times republished that editorial as its own, the paper would face public excoriation by modern Baptists. Also, if you told modern secularists that their views are a throwback to Baptists, they probably wouldn’t take too kindly to it, either.

As historian Leigh Eric Schmidt writes in the excellent “Consumer Rites: The Buying and Selling of American Holidays,” “conflicts about how to solemnize Christmas, particularly how to sort out Christian and commercial enactments, have been a recurrent feature of American religious life,” arguing that “the American marketplace has served for more than a century and a half as a site of competition about the meanings of Christmas.”

Blame Christians and the Market

For liturgical Christians, Christmas is one of our holiest seasons, a major point of celebration of God taking on human flesh to save us. For Western Christians, the 12 days of Christmas begin—note: begin, not end—on Christmas Day. For capitalists, Christmas is the holiest of seasons, as well. Retailers depend on good sales from November’s Black Friday through the beginning of January to make profits for the year. Schmidt says this tension between the religious practitioners and the capitalists seeking to exploit their fervor is why Christmas “has remained a realm of contest, not fiat, a place of disaffection and estrangement as well as joy and excitement, a site of not a little ambivalence, paradox, and contradiction.”

It would be easy to blame problems of Christmas in America on the enlightened secularist denizens of the Left who oppose every crèche in a public square or Bach cantata sung at a public school. And they certainly will come in for their fair share of the blame. But their effect on deChristianizing the holy day came later and built upon the strong foundation laid by what we might now term the Christian Right. At the same time, this commercialization and attempt at desacralization is a big reason why Christmas remains a favored holy day. When was the last time you saw an article about the War on Whitsunday? (I secretly hope for Wars on Whitsunday so that Christians would remember they’re supposed to mark it.)

George W. Curtis, a founder of the Republican Party and editor of Harper’s, wrote a piece about Christmas for the magazine in 1883. In his essay, he thanked the Puritans for contributing to the widespread observance of Christmas by removing the theological foundations for the holiday. Christmas “could not be the most beautiful of festivals if it were doctrinal, or dogmatic, or theological, or local. It is a universal holiday because it is the jubilee of a universal sentiment, moulded only by a new epoch, and subtly adapted to newer forms of the old faith,” he wrote.

The War Between Church and Sentiment

He wrote this almost in protest of how the holiday was becoming quite religious. A burst of Christmas hymns in the nineteenth century and the rising popularity of the day made Christmas a major religious event by the end of the nineteenth century, “a time to recount biblical stories of the Incarnation, sing religious hymns, stage Sunday school pageants, view Nativity scenes, decorate church interiors, hold special services, and contemplate God’s mysterious work of redemption,” according to Schmidt.

But by the 1940s, a non-religious Christmas had become an integral part of American life. “Holiday Inn,” “Miracle on 34th Street,” “White Christmas,” and “It’s a Wonderful Life” are some of the most popular films of all time, but they are devoid of Christianity. Seriously, have you seen “White Christmas,” the 1954 musical featuring Bing Crosby, Danny Kaye, and Rosemary Clooney? It’s a great movie, but it has absolutely nothing to do with a Christian version of Christmas. Or even much of any other kind of Christmas.

“White Christmas” composer Irving Berlin was a Russian Jewish immigrant, which explains much of this. But how many other “Christmas” songs are any different? “Chestnuts Roasting on an Open Fire,” “Frosty the Snowman,” “Grandma Got Run Over by a Reindeer,” “I’ll Be Home For Christmas,” “It’s Beginning to Feel a Lot Like Christmas,” “Jingle Bells,” “Let it Snow,” “Rudolf the Red-nosed Reindeer,” “Silver Bells,” “Winter Wonderland,” and “Santa Claus is Coming to Town” also make no mention of religious themes. The songs, which were written during the twentieth century, are all warm-hearted and familiar without any of the theology of Christ’s incarnation.

Again, to cut a lot of history short, retailers and capitalists in general are responsible for both the rise of religiosity in commercial ventures, and their decline. American retailers figured out that religious window trappings encouraged Christian shoppers at Christmas. Because of various non-liturgical influences in American churches, storefronts frequently outdid churches in religious symbols.

Beginning in the late nineteenth century, Wanamaker, a downtown Philadelphia department store, decorated its Grand Court for Christmas with wood carvings of the apostles, golden candlesticks signifying the seven churches of Asia, angel statues, and giant tapestries of the Three Wise Men and Mary, Joseph, and Jesus. The world’s largest organ accompanied shoppers in hymn sings twice a day. Hymnals were printed up for shoppers featuring overtly Christian hymns, such as “O Come All Ye Faithful,” “Hark the Herald Angels Sing,” and “All Hail the Power of Jesus’ Name.” Beginning in the 1950s, however, the displays were replaced with a “dancing water show composed of colorfully lighted fountains,” Frosty the Snowman, and Rudolph the Red-nosed Reindeer.

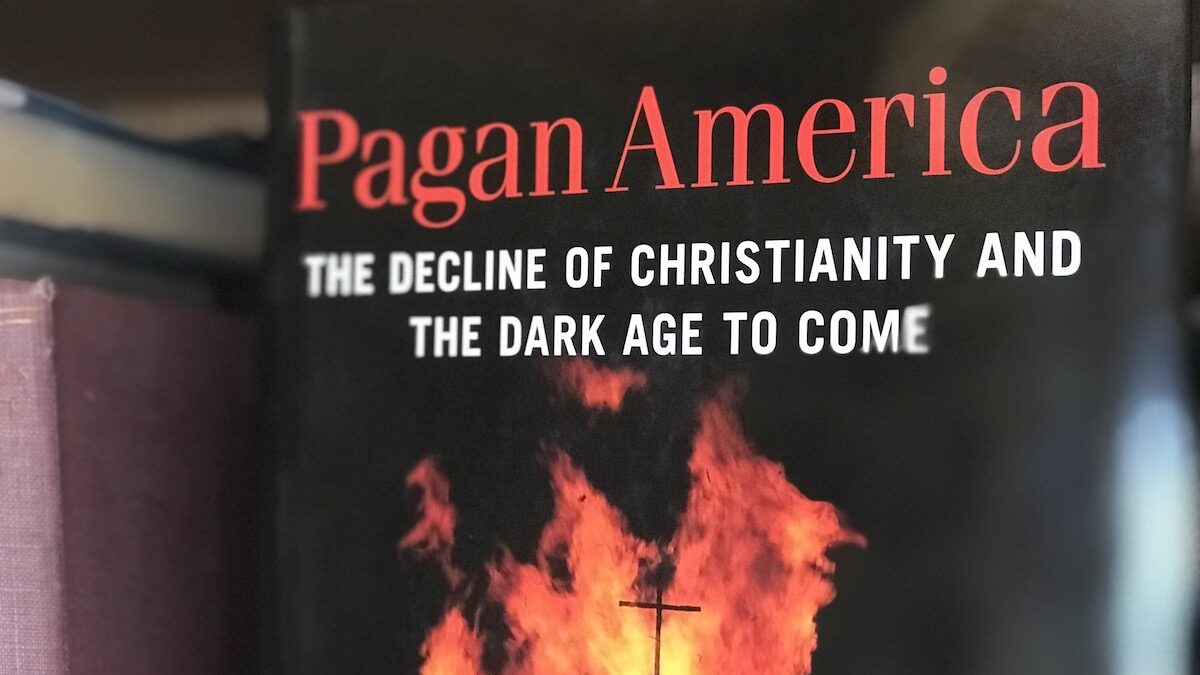

An article noting the rather lacking homage to anything even remotely Christmas-season-related on the Starbucks Christmas cup is nothing to get your panties in a twist about. It’s actually an interesting observation about the ebb and flow of both capitalism and Christianity.

While we’re thinking about how we mark sacred days in a commercialized culture, I’ll offer a humble plea that the real War on Christmas is the destruction of Advent, the penitential season that precedes and prepares us for Christmas. Liturgical seasons are a great way to get the proper amount of preparation and contemplation before the big celebration.