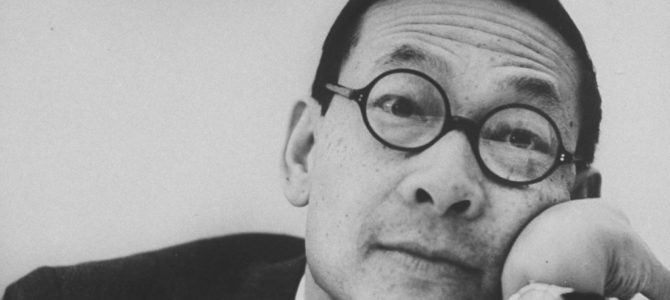

The world-renowned American architect I.M. Pei passed away last week at the age of 102. He left behind many iconic designs, such as the glass pyramid at the Louvre Museum and the geometric John F. Kennedy presidential library.

Many tributes to him since his passing emphasize his Chinese roots. But his long and productive life is a shining example of American exceptionalism.

Ieoh Ming Pei was born in 1917 in China. The Pei family was a wealthy family in Suzhou, a city known for its delicate waterways and canals, and exquisite gardens. But the early 20th century saw China fall from a great power into a war-torn nation. Decades of failed wars against foreign powers not only ruined the country’s economy, but also severely wounded national pride.

Led by Sun Yat-sen, the Chinese people overthrew the last emperor of the Qing dynasty in 1911, officially replacing the more than 2,000-year-old imperial system with a republic. Instead of a rebirth, however, China fell into deeper turmoil. A once-united country was divided among foreign powers, domestic politic factions, and authoritarian military generals. The majority of Chinese people lived in poverty and misery.

Because of his family’s wealth, Pei lived a relatively sheltered life as a teenager. In 1934, when he was 17, he left China for the United States. He first went to the University of Pennsylvania, later transferring to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. After getting his bachelor’s degree in architecture from MIT, Pei decided to stay in the United States due to the ongoing Sino-Japanese war (1937-1945).

His timing was good. Since China and the United States were allies during World War II, Americans’ attitude towards Chinese immigrants changed from antagonism to friendship. Not only did Americans offer China financial aid and military assistance to fight Japan, but the American government also changed the United States’ discriminatory immigration law by repealing the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act through the 1943 Magnuson Act. The Magnuson Act established an annual quota of 105 immigration visas for Chinese immigrants. That doesn’t sound like much, but it changed Pei’s life forever.

Had he gone back to China, Pei might not have survived either the Sino-Japanese war or the Civil War (1945-1949) between Chinese Communists and Nationalists. An estimated six million Chinese died in the Sino-Japanese war alone.

Even if he had survived these wars somehow, his family’s wealth and his western education would have made him an easy target of the Chinese Communist Party’s countless persecutions from 1949 to 1976. An estimated 20-30 million Chinese perished during this period, including many industrialists, novelists, poets, and artists. Those intellectuals who survived rarely produced anything extraordinary afterward, because without freedom, creativity dies.

While many of his contemporaries suffered in Communist China, Pei was thriving in the United States. He received a master’s degree from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, studying with German architect Walter Gropius, one of the masters of modernist architecture and the founder of the Bauhaus art movement, which united fine art with industrial design. A few years after graduation, Pei became an entrepreneur by starting his own firm, I.M. Pei & Associates (today it is known as Pei Cobb Freed & Partners). One of his early commissions was to design the Mile High Center in Denver, Colorado, affectionately known as the “Cash Register Building.”

His big career break came in 1964, when he was commissioned to design the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library. It was said that Jackie Kennedy visited a number of architects. Pei was the only one who didn’t try to sell her a definite plan. Instead, Pei said “he would like to propose his idea after he spent more time contemplating what John F. Kennedy would have liked.”

Mrs. Kennedy explained later that she picked the relatively unknown and inexperienced young architect because she appreciated his client-focused approach and she thought Pei “was full of promise, like Jack; they were born in the same year.”

The J.F.K. presidential library was completed in 1979. It’s an impressive black and white building that combines several distinctive geometric shapes, which foretold Pei’s future signature style. A grateful Mrs. Kennedy wrote to Pei in 1981, “I will always think of it as a monument to your spirit–to your humanity and perseverance.”

Riding his success from designing the JFK library, Pei spent the next few decades designing many remarkable buildings in the United States and around the world, including the National Gallery of Art’s East Building, the Bank of China building in Hong Kong, and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha.

Of course, the building that won Pei the most global fame is the glass pyramids entrance to the Louvre Museum. He took an ancient design and built it with modern materials like glass and steel. The glass pyramid, simple and elegant, stands out yet compliments its historical surroundings. Anyone who visits the Louvre can’t help admiring Pei’s creativity and artistry.

Last Saturday, the Dallas Symphony Orchestra offered 102 free tickets in honor of Pei, who designed DSO’s home and a number of public buildings in Dallas. It’s a kind gesture to honor a fellow American who left such distinctive cultural imprints in America and around the world.

Pei once said “Life is architecture and architecture is the mirror of life.” His art is certainly a mirror of his life. Although he was born in China and those classic gardens in Suzhou might have influenced his aesthetics, his designs are clearly western and modern.

There is no doubt that Pei’s talent and work ethic were the main drivers of his success. It’s also fair to say that he owed his long and productive life to the fact that he lived in the freest country in the world. The liberty he was afforded in this country helped him get the best education, start a business, and be as creative as he wanted to be without external constraints.

In this meritocratic society, Pei wasn’t held back by his race. Instead, he was able to compete, win important commissions, and attract a diverse clientele based on his merits.

Pei’s life is something many of us can relate to. Few of us can compare what we have done to his monumental achievements, but all of us can live to our full potential in a free society. That’s what American exceptionalism is all about.