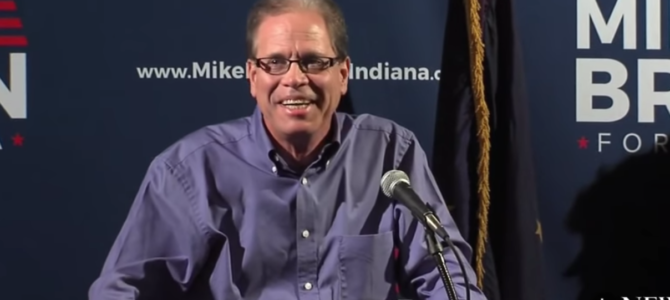

Executive Editor Joy Pullman interviewed Senator Mike Braun from Indiana on the current nominations for district judges, Silicon Valley, the national debt, and more. Listen here or read the full transcript below, which has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Joy Pullmann: Senator Braun, I voted for you in this last election twice in both the primary and the general election, so that is my preface for wanting to ask you some direct question as a constituent, a conservative, and an American. So you want to talk about judges, but I have some other questions here, so let’s make the most of our short time together and we’ll do this quick hit style.

So the Senate Judiciary Committee is set to consider the nomination of Holly Brady and Daiman Rayladi for U.S. District judges in Indiana’s Northern District. These are part of the one-third of the federal judgeship that the president recently renominated because Democrats are refusing to consider the nominations of many judges. Will these two judges apply the Constitution faithfully and be a judicial team for efforts to overturn Roe v. Wade and protect state constitutions from pro-abortion interpretations?

Mike Braun: I think the two judges and along with many others across the country, I think the slate that the president has brought to the forefront has been good across the board and I think the biggest issue not been with the quality of the candidates, but the speed at which we’ve been able to get them through the process. One of the things I knew when I was coming here was that it was basically a place that tried to resist and complicate the process. When I learned the mandatory time and debate that has to be held on each nominee, it’s really part of what’s wrong with the system, but the Dems did block a bunch of nominations from getting through prior to the end of the year, we got a lot of them coming up.

Many require eight hours to where you do nothing before you can vote on them so there’s kinda of a built-in jammed-up part of the system on getting any of the judges across, but I think these two as well as almost everyone I’ve looked into would be a cabinet appointment as well as some of the folks that that need to be filled in across the country. I think the nominees are great; it’s the process that’s messed up.

JP: What are your top criteria for vetting judicial nominees?

MB: Well I want to make sure that they are gonna always interpret the law, stick to the Constitution, not making any groundbreaking headway when it comes to tweaking an interpretation to, in some way, put out a political point of view. I think that one reasons I like Brett Kavanaugh is he was clearly one that was gonna interpret the Constitution. He didn’t look like he was gonna try to make law from the bench and those are gonna be the most important criteria for me and, again, I think what we’re up against is we got a system that actually approves judges that I’m gonna weigh in increasing. Maybe we give that same benefit to the Democrats down the road when it comes to their approving nominees, but I think the fact that it takes so long to get this done is where I’m gonna weigh in on the process of any nominee––whether it be a cabinet position or a judge.

JP: I assume you favor fully vetting folks but it sounds to me like more of what you’re saying is there’s a difference between vetting and just obstruction for the sake of obstruction.

MB: I think that was crystal clear as much as we were all glued to the Kavanaugh proceedings that that’s the case and it’s a shame it’s gotten down to that and a lot of the rest of government. Now that I’ve been here a little over a month, the process of getting a bill though, even if it’s innocuous––it’s got so much delay to it. I’m okay with the fact that we don’t we don’t need to be a law-making machine, but on stuff that is really important where I think citizens across the country, Hoosiers, in terms of who I’m gonna listen to first, they wanna see a few things get done but I think both sides have been guilty of thwarting the process.

JP: Now you were very strong in the campaign on presenting yourself as a pro-business lawmaker. Of course, you personally have a business background and I am also very pro-enterprise; My dad is a small business owner and other members of my family are very successful businesspeople, but as I’m sure as you know, Indiana has been ground zero for the break-out of a new dynamic between business and politics.

I’m talking about our Religious Freedom Restoration Act battle a couple of years ago which you participated in as a state legislator. That battle continues as Republicans in our state are trying to strangle the First Amendment’s protection for speech and religion by passing so-called hate crime laws. So where do you stand on this issue at the federal level and how can Republicans regain credibility among their voters after constantly capitulating to businesses that push hard-left culture on red states like ours?

MB: I was there in the middle of all that that was probably of the three years I spent in the state legislator. The time where that came to the forefront in terms of where you really have to be careful because all we were trying to do then was parallel to the federal statutes and that wasn’t good enough. Then it got viewed by the opposition that it was favoring discrimination and to me what we were simply trying to do was in those cases where you got various First Amendment issues that might conflict with one another and you got a topic of discrimination versus the subject of religious freedom––that’s where courts are gonna have to step in and try to make sense of anything that’s gonna cloud it, or you’re just gonna have natural conflicts, so I thought we did the right thing, but you’re right then mostly large business across our state weighed in and then of course you did the fix.

The fix, I thought, was just a clarification that there was never discrimination intended but we all know in the game of politics––everything gets either nuanced or magnified in a way that benefits one side or the other politically. That’s what happened there when it comes to hate crimes and now we are one of five states that I think doesn’t have one officially on the books but we’re also a state I think just like during the religious freedom versus discrimination argument, we do not have a ton of them that have surfaced in case law. Whether we’re lucky as a state, I don’t know, but I’m always gonna err on the side that we probably stick with what we’ve been given in the Constitution––whenever we start trying to modify accordingly you get into the difficulty of how do you craft a bill like they’re talking about now in our state legislator to make sure you balance everybody’s interest and is something isn’t broken why try to fix it?

JP: Typically my position is punish the crime so if someone does something violent against someone they should be punished for it, right? I mean I don’t see a place for the government reaching into the people’s minds and hearts and stringing them up for thought-crimes as evil as it may be to harbor discriminatory racist attitudes against other people. Once people act on those bad ideas we’ll punish them like the law already provides for.

MB: You said it very articulately and that’s the fact that whenever you do this kinda thing I think it opens up a lot of other possibilities, unintended consequences, so no, I agree that if no one is wanting to do anything in the case of religious freedom that would’ve promoted discrimination and here in trying to flesh out a hate crimes bill you then get on to that slippery slope of “are you trying to preempt thought” and that’s the complication you get into whenever you try to refine something into legislation.

JP: I’m gonna talk about another kind of touch of flash point difficulty with business that’s been going around lately as well. So as I’m sure you know, Silicon Valley has been recently––this is debatable––but some people are saying that Silicon Valley is threatening American’s rights to both free speech and privacy with their massive data collection on people and reselling that information without people’s knowledge as well as seeming to put their thumb on the scale with censorship through the platforms we all know such as Google, YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter. Do you think it is time to recognize platforms as these as publishers liable for the content they publish since they now ideologically select what can and cannot be posted on their platforms?

MB: Well I think the fear of what you’re talking about in general is something that’s an issue in and of itself and that you have always be careful with that you have somebody gathering private information and doing what they want with it. The other factor here is the entities that we’re talking about are basically monopolies in most of their segments and that bothers me as well.

Whenever you got some component of any industry that basically monopolizes it, it’s got its own issues that can develop and here when it comes to mining private data, selling it, or pushing a particular political point of view by either suppressing or letting it out there in a way that you’re favoring one point of view over the other––that’s kind of a tricky place to be.

I think that there are two issues there, I think that the industry is too concentrated––I don’t like the fact that there aren’t broader points of view in participants––and then I think what you described as the issue of what they’ve been accused of I think it’s worth further investigations.

JP: And so what do you think Congress should do or consider doing about that?

MB: Well, there are some, I’m a free-market guy that generally doesn’t like government to get involved unless you violate something whether it comes to environmental laws or whatever you do there’s gonna be penalties and consequences for bad behavior but when you try to be comprehensive and control stuff in general that’s where, I think, government goes too far. In this case, I don’t know if there is a counter force that’s can deal with companies of this size that control so much information and that we found out that they’re using it in ways that we probably all never knew that they would and then you look at the counter part of what’s happening in China. When I read and heard about how that’s controlling so many dimensions of citizen’s lives that shows you what it can evolve into down the road. Not saying that there’s any direct comparison currently all I’m saying is I’ve heard what’s happened there and again those are frightening things to consider.

JP: We might wanna grease the skids for that kinda infrastructure possibility.

MB: Like I say I think in this case I think there ought to be hearings to make sure that there’s not more there than what we’ve already discovered and that I also think, and this would be from the commercial side of it, that we’ve got anti-trust laws, we’ve got rules that in a so-called free market, you can’t have a monopoly, and that bothers me as well. So I think the whole industry has gotten so large and grown so quickly and its selling a product that’s not tangible and some of the things we’ve heard that have occurred, I think it’s worth asking some questions about.

JP: Now I was pleased to find that you have been assigned to the Senate Health Education Pensions and Labor Committee because education is my special area of interest and that committee is expected to take up the main federal higher education law for renewal this spring and summer. So Federal Reserve research shows that for every single dollar in federal subsidies colleges increased their tuition by 55 to 65 cents. So how do you think Congress should undo its bloating effect on higher education?

MB: An interesting question because there are two parts of society that need some type of…it’s gotten out of control when it comes to the cost of it and it’s a cost of healthcare that ironically has recently been eclipsed by the growth rate of post-secondary education, and neither one of them operates in any type of free-market so to speak.

JP: Or maybe any market at all.

MB: Well, especially with education and healthcare, maybe primary care, is starting to show some rumblings that is just fix the system which has been broken for many years I it took the whole issue onto my own company 10 years ago as it relates to insurance companies. It is the farthest thing from free enterprise. Health insurance was an affordable fringe benefits many years ago, it now cloaks the whole process by shrouding pricing, there’s no transparency, people have higher deductibles now, and there’s no way to shop around.

Higher education, both of which parents and families I think put as their two highest priorities––wellbeing health-wise and education-wise––has gotten to where through in endowments through everything that distorts the revenue side parents have gone along with it and not been engaging shoppers for the best educational value because they’ve defaulted that we just need to do this regardless of the cost.

Whenever you don’t ask how much something costs, I think most parents and high school graduates do that before they choose a college but if a lot of its being done through scholarships, loans, and revenue enhancements that are unrelated to the people that still have to pay part of the bill, you end up with a bubble that we’ve got currently.

I was with Mitch Daniels on Saturday and we talked a little bit about––of course he’s frozen tuition I think in the seventh year, really done a lot to actually control costs. I’m guessing he might be one of a handful of university presidents that have really done it and it really needs to be treated as well as healthcare in a way that if we wanna prevent having a bubble created like in the form of student loans…which we’re almost kinda there, gotta start addressing how do we bring the cost down.

JP: The last time Congress passed a federal budget was 2006, which is obviously 13 years ago. Your first bill introduced as senator would not allow members of Congress to receive their salary if the government is shutdown, just like other federal employees during a shutdown. What parts of the federal government need to be cut so Congress, including you, can finally start getting America’s bankrupt finances in order?

MB: My bill is actually “No Budget, No Pay” and technically I guess you can say shutdown because when you don’t have a budget, you’re gonna go into a shutdown, but this bill you got a year to get a basic budget done and you’re right, it hardly ever happens. I’m on the budget committee and speaking to Chairman Enzi, he is a guy that, thank goodness, he’s got a sense of humor because there are budgets that are put out there…they just never get adopted and the system has gotten used to it and this bill would be about if you don’t craft a budget having a year to do it, nobody there gets a paycheck and, until there are real consequences like that, I think there ought to be pension reforms. I don’t think congressmen and senators ought to be getting pensions when nobody else does. This place is gonna keep doing what its always done: not producing budgets, producing trillion dollar deficits, throwing it on top of $21 trillion in debt, and, to be honest, nobody here but a handful of us seem to even get excited about it.

JP: Do you think that really has very much teeth to it though? Because the members of Congress, I mean, the proportion of them who are independently wealthy is much, much higher than that of the U.S. population, so a lot of them can stand to go without their congressional salary and pensions and be just fine.

MB: There would be that component. There are some here, though, that aren’t, but there should be some type of penalty rather not having it and, in my opinion, you’d raise the consequences over time. The fact is, now, there is no accountability, there are no penalties, and we have really a joke of a budgeting process for the biggest business in the world: our country’s federal government. At least there a few more people here now have done budgets and have made payrolls and actually know how you do it and the amazing thing is even many on my side of the aisle don’t want to give up what they like in the federal government. You’re never gonna do this unless it’s across the board and it’s gonna have to be done and hopefully before we have a calamity. You can maybe laugh all this stuff off when you had maybe just five trillion in debt but when you’ve-

JP: Just five trillion.

MB: That’s many years ago, you know, now we’re at twenty-

JP: I’m laughing because I can hardly conceptualize five trillion.

MB: Well I’ll tell yeah how big $21 trillion is; when interest rates go up 1 percent, that’s $220 billion, and that interests rates have gone up basically 2 percent over the last year, so we’ve structurally built into our already-high deficit another $300 to $400 billion in interest alone, so that’s gonna push our annual deficits from a trillion (where they are now) to, in a few years, $1.5 trillion. Sooner or later, people will quit lending you money and you’ll fix it through the old-fashioned way of a financial calamity.

JP: Oh I thought you were gonna say wealth confiscation, obviously no, just kidding. What about the second half of my question though? You said “look you obviously gotta get in there and whether you like it or not you gotta cut some things,” so what things would be on your chopping block to balance the budget?

MB: You know, I was asked that question in the first debate in the primary, and Tony Katz at WIBC did the debate and he thought I was evading the answer and my two opponents mentioned a few things that wouldn’t have added up to hardly anything. I said you gotta do it across the board and he came back to me and he said “Mike I’ll give yeah one more chance to answer the question,” and I said “I’m gonna answer it the same way, Tony. It oughta be: you do it across the board through a freeze or a 1 percent decrease and, look at it this way, if you’re spending today you think that that’s the mix that makes sense; You just either had done a continuing resolution or you might’ve done a part of the budget but who in the heck is gonna miss 1 out of a hundred of something, which would be a 1 percent cut anyway. There’s no backbone, there’s no discipline here, people are used to kicking it down the road, it’s gotta be across the board.” I believe-

JP: But you know the size of the annual deficit it’s way more than 1 percent of the federal budget every year.

MB: Ironically, most of our deficit are driven by the fact that they’re automatic escalators built into nearly three-fourths of what we spend, which is roughly $4.3 trillion, and we’re only bringing in $3 trillion. Imagine if any of your family business were running 30 percent losses and then wanted to go to the bank to get a loan––they’d be laughed out of the loan office.

So if you do it across the board into where you freeze or reduce, it’s amazing how quickly the arithmetic brings you into a balanced budget.

Listen to the full interview here: