I spent an entire year reading through the novels of James Michener, especially the “saga” novels of the 1970s and 80s. In the process, I discovered an American master I never suspected existed. I spent many pleasurable hours listening to the audiobook versions of the books when I wasn’t reading words on a page. The reading I did was all on my Kindle. It’s odd, but not having to either buy reprint editions or crack open dusty and crumbling paperbacks made reading Michener seem new to me, as if I were encountering contemporary books instead of novels that are thirty to forty years old.

You, like me, may have been put off from reading Michener before by bad advice. But now that we are older, wiser, and don’t give a damn what our professors or literary betters think, I believe you’ll discover a hell of a writer in Michener, well worth reading even if his memory does seem to be fading from the culture.

Back when I was in college, Michener was at the top of the publishing mountain — and at the bottom of his reputation among the smart set. You didn’t hear James Michener’s name spoken among literary sorts without a sneer attached. It was conventional wisdom that Michener was a hack, a producer of word-pabulum — and besides, he wasn’t even a real writer at all, at least not anymore. Other people wrote his books.

At the time, I already had some evidence to form a low opinion of him. When I was a teenager and cutting my teeth as a reader by picking up anything and everything that came my way, I’d started his doorstop novel “Centennial,” about the settling of the American West, but found that the beginning chapters were so ponderous and meandering, I’d had to give up on it.

This was particularly damning in my eyes at the time because back in my callow youth there was rarely a book I started and didn’t finish, even if it almost killed me. Nowadays my patience for getting to the end of novels I’m not that into has, let us say, contracted considerably. But I wish I’d finished “Centennial” back then, even though it isn’t Michener’s best.

The Saga Novel

Michener wrote three huge bestsellers in the 1960s, after a string of successful novels in the 1950s. He’d been a big literary deal since the late 1947 when his first novel, “Tales of the South Pacific,” was made into the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical and later into the blockbuster film. But it was in his later years (Michener was 73 years old in 1980) that he seemed to transcend publishing itself in a way few writers have managed. A new Michener novel became akin to a force of nature in American culture, leaving overflowing coffers of cocaine money at Random House and a slew of forgettable miniseries in its wake.

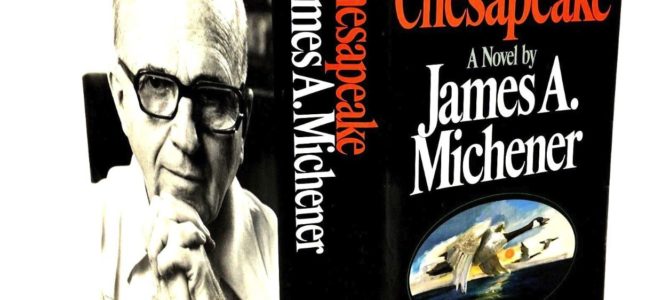

It was in the 70s that Michener perfected his kitchen-sink, “saga” novel approach and twice hit the top of the annual bestseller list for the biggest selling book of the year. “Centennial” was the best-selling novel in hardcover in the nation in 1974, according to the Publishers Weekly charts. “Chesapeake” was the number one selling hardcover novel of 1978. The mass market paperback sales were similarly phenomenal, of course.

These enormously successful books opened an astonishing, decade-long run, starting in 1980 with “The Covenant” at number one overall for the year. Space (a weaker piece) took the number two overall spot in 1982. The amazing “Poland” was number two for 1983. The equally great “Texas” hit number two in 1985, “Alaska” took number five in 1988, and number five in 1989. Michener would make the Publishers Weekly yearly list once more, with my second favorite Michener, “Mexico,” at number eight for the year in 1995.

Did Michener write all of his books? In one sense, who cares? If the story, characters, and setting are great, what conceivable difference could it make to a reader? None. On the other hand, you don’t want to be lied to with a name on a book cover — it does matter if he put very little that was original into the production.

Then there were the literary snobs. Michener had far too broad a base of readers to be endured by such people. How could you claim to have special knowledge of an artist genius when even Republicans read him?

So at the height of his success, Michener’s reputation began to languish. Wasn’t he, after all, really just a hack who didn’t even write his own books? Inquiring minds wondered. And insinuated they already knew the truth.

Absence of Irony

The fact is that Michener employed a bunch of research assistants over the years. Some of them were just that, but others were accomplished writers or editors in their own right who, at times, wrote some first draft sections of the books. Michener would then extensively rework these parts, putting his own touch upon them.

Errol Lincoln Uys, an author and the former editor-in-chief of Reader’s Digest South Africa, has an excellent online remembrance of his stint as Michener’s chief researcher on “The Covenant,” a Michener saga novel about the development of South Africa. Uys lays out the process of his work with Michener very clearly and personally.

So, in a sense, yes, some Michener novels are collaborations in the loose sense of the word. They may not have the collaborator’s name on the cover, but Michener acknowledges his coworkers handsomely enough in the front matter. And, of course, they were all well paid.

The books are certainly not ghost-written, work-for-hire numbers. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, in the final analysis. But they aren’t.

Why does any of this matter?

Because, as I discovered for myself last year, Michener got a bad rap. The books are good. Very good. The guy can tell a tale. He paints a beautiful, rich setting from which the tale naturally arises. And, best of all, he tugs at your heart and tickles your mind with characters who seem to effortlessly flow through the setting and bring the plot to life, often in an unexpected and delightful manner. This is pretty much the definition of the successful novel as it comes down to us from the 19th and early 20th century.

But then came the 1960s. After that, things got weird and unpleasant. By the 1980s they were beyond unpleasant. The literary novel got downright toxic. Deconstructionism and the whole gamut of modern literary theory descended there like Smaug on Erebor, and by the late 80s, irony ruled the day.

If there’s one quality Michener does not traffic in, it’s irony. Michener is striving to make each novel into a mirror of nature in spirit and, especially in a Michener saga, in physical fact. If you don’t think such a thing is possible, you have to conclude that the work is worthless. Or at least, you have to say that’s what you think, even if you do hide a copy of “Poland” in your bathroom to read when nobody’s watching.

The Setting As Character

I do have one big caveat about Michener’s work. Like many writers of historical fiction, Michener seems to lose his marbles when his stories or the character’s concerns get close to contemporary times and attitudes (see, for instance, Tolstoy’s utterly pointless digressions on freemasonry in “War and Peace”). Michener was a political idiot. And, like most fiction writers, he thought he knew everything.

Michener was the adopted son of Quakers (he never knew his biological parents). He was mostly an autodidact, and his thought was an odd blend of conspiracy theory and Society of Friends faux naiveté when it came to the gears and levels of the contemporary world. His political judgment leads to a few ill-advised and, because he was Michener, seemingly endless detours in the novels. The final chapters of “Chesapeake” are tough going (advice below on which section to skip). They are also evidence that, for better or worse, Michener wrote his own books.

Perhaps for the same reason, outside of the great sagas, Michener is a middling quality novelist, though certainly worth reading. But he figured something out, or stumbled into it, late in life, and it buoyed his final work beyond its time. He figured out how to use setting as the main instigator and mover in a story. In a Michener saga novel, the setting is virtually a character in itself.

But he did setting all wrong, at least according to modern theory. He used settings to give his characters freedom, not oppression. For Michener, setting is far from a Marxist or deterministic quality in fiction. Instead, setting gives Michener’s characters meaningful choices to make. They may be a mid-level knight in 12th century Poland during the Tartar invasion. They may be a slave deep inside a Mexican silver mine. They may be an oysterman fighting a gang war for control of the beds of the Chesapeake Bay. Wherever and whenever they might be, dealing with the specifics of the particular setting keeps Michener’s characters from getting lost in a cloud of their own cogitation.

Real storytelling rests on the moral assumption that humans do not create the meaning and value of life, but discover it. A novelist’s job is to mine that vein. Michener wasn’t a genius, although based on some of his statements, I’m pretty sure he thought he was. He wasn’t much of a philosopher. Or even, really, a masterful historian, although he tried to be.

But he sure was a hell of storyteller.

Read him.

The Top Five

Here is my pick for the top five Michener novels. “Chesapeake,” I think, is the true masterpiece that stands above all the others. But start anywhere. It’s a long, splendid journey. And when you’re done, I’m willing to bet you’ll wish there were more.

1. Chesapeake

As good as it gets. This is the saga of the Chesapeake Bay area, particularly the upper Chesapeake, from the days of the Powhatans, Choptank, and Nanticokes to the present. Michener starts it off with the compelling flight of a Susquehannock man named Pentaquod from his village after he comes out on the losing end of a debate on whether or not to go to war with a peaceful neighboring group (he’s against it). He ends up finding a new people on the eastern shore, and establishing a dynasty whose descendants we follow throughout the book. Plus, he discovers softshell crabs! The book continues with dramatic contact stories between Europeans, Indians, and Africans that are filled with love and bigotry, tragedy and triumph. We follow the Catholic Steeds, the Quaker Paxmores, and the godless Turlocks through sea stories, slave tales, plantation stories, war stories — up to the book’s present in the 1970s. The ending is decidedly weaker than the rest of the book, and you can skip the “Voyage Fourteen” section without losing anything other than a tortuous take on wetlands management theory and wacky 1970s environmentalism. Otherwise, this is Michener’s masterpiece.

2. Mexico

This one has a wonderful modern-era framing story that revolves around bullfighting and coming to terms with one’s home town, in this case the fictional Mexican city of “Toledo.” Norman Clay is an American journalist who is still intimately connected with the town of his birth and with his extended family. He’s a descendant of the Clays, who came from Virginia, and from two branches of the Palofoxes, one purely Spanish in ancestry, the other Spanish and Mexican Indian mixed. I learned far more, and I got a much grander feel, for bullfighting than I did from “The Sun Also Rises,” “Death in the Afternoon,” or anything else I’ve ever read on the subject. It even put my one rather disturbing trip to the arena in Pamplona into perspective. Michener’s description of the silver mine on which Toledo’s wealth was based, and the way the mine was worked by Indian slave women, is awesome, harrowing, heartbreaking, and unforgettable.

3. Poland

I went into this knowing next to nothing about Polish history. What a place! It is a frontier state, the border of Europe and Asia, of Christianity and … the world before, which was still very much a threat to overwhelm and destroy the place at any moment. Slavic resilience. Castles with weird animal menageries. Plus, we get a multiple perspective account of the battle at the Gates of Vienna, when Jan Sobieski saved Europe from the Turks. Lots of deeply moving stories within as we follow the generations of several families of various social classes, and some tragic moments that will rend your heart.

4. Caribbean

If you ever wanted to really understand pirates, buccaneers, and the pirate’s life, this one’s for you. It’s got Blackbeard. It’s got Sir Francis Drake (who Michener presents as quite a jerk). There’s a great battle segment at Cartagena. The later stretches of the book have a complex presentation of the social strata of the islands, particularly among those of mixed European and African ancestry. Plus, there’s a nuanced (and sinister) take on a Rastaman character and even a brief history of the Rastafarian movement, which is far weirder than I ever supposed.

5. Texas

The framing story on this one is weak. We follow a historic commission flying around to visit various sites it will include in a recommendation for a new school history curriculum. But the historical fiction is top notch, especially when it comes to the Spanish settlement of San Antonio. This one has scenes as brutal as anything in Cormac McCarthy or Larry McMurtry’s historical novels. The violence and pathos comes through particularly well in Michener’s account of the Battle of the Alamo, which is really fantastic.