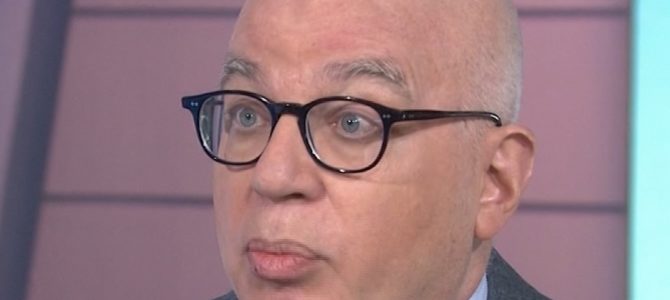

“Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House,” Michael Wolff’s entertaining new book, is a mix of wishful falsehoods, compelling fictions, and a lot of stuff we already suspected about the White House. Even honest antagonists of Donald Trump can concede as much.

But treating it too seriously not only diminishes the president — who does solid work on this front all by himself — it diminishes journalism and incentivizes reporters to sensationalize their coverage, which is already a growing problem.

Even before I got my hands on “Fire and Fury,” the kind of fun book I’ve been reading with high levels of skepticism for 20 years, I’d run across a contention that I knew to be patently false. According to the author, the late Roger Ailes once suggested that the president-elect make former House speaker John Boehner his chief of staff. Trump, claims Wolff, answered, “Who’s that?”

“OMG! Donald Trump doesn’t didn’t know who John Boehner was in 2016!” went the Twitter cry. But I had interviewed Trump in 2013 regarding the tax ceiling fight, long before ever contemplating his presidency, and it was obvious he knew Boehner rather well even if he knew virtually nothing about the debt ceiling.

Since then, reporters (many of them, it should be noted, are critical of Wolff) and others have uncovered plenty of evidence debunking the Boehner story, and numerous other assertions in the book. Not that this discouraged his antagonists. The president is suffering from dementia, they now argue — an attack that comports neatly with the new push to overturn the 2016 election on grounds of the president’s mental fitness.

Perhaps he does have dementia. Or perhaps Trump misheard. Or perhaps Trump didn’t recognize the pronunciation of the name. Or perhaps the president was mocking the choice of Boehner in the Trumpian style. Or perhaps the story never happened.

That’s the problem with a book of rumor-mongering. You can never know what’s true, though people always tend to believe the tidbits that reinforce their worldview. Not that these sorts of tomes are new. Every president has his Kitty Kelley. What is new, though, is the wall-to-wall coverage of the book. Wolff has given outlets a convenient excuse to repeat unverified stories about the Trump administration that they couldn’t talk about otherwise. In doing so, some are left to defend book’s abstract truths.

“CNN has not independently confirmed all of Wolff’s assertions. But the broader portrait of a President surrounded by aides and advisers wary of his temperament has been borne out in conversations with officials over the past year,” @kevinliptak reports https://t.co/EuE79cwuRw

— Brian Stelter (@brianstelter) January 7, 2018

This was astonishing thing to read. Imagine members of the press in 2012 arguing, “Sure, the Ed Klein book about Barack Obama is filled with unsubstantiated anecdotes, exaggerations, and untruths, but the spirit of the narrative rings true, so we’re going to cover the heck out of it.” It’s far more likely we would see, “CNN has not independently confirmed many of Klein’s assertions, so we doubt the veracity of the book as a whole.” This was a journalistic standard.

Not to mention that the broader narrative of “Fire and Fury” doesn’t always seem to align with reality, unless you believe Steve Bannon’s perception of the world. Reading the epilogue of the book, it’s rather obvious that the former White House chief strategist drove Wolff’s narrative, attacking his enemies and getting basic facts about events and people wrong. For instance, the description of senior policy advisor Stephen Miller as an uneducated “intern” whose lack of policy chops drove him to Google for how to write an executive order is absurd, no matter what you make of his opinions.

+ even if some things are inaccurate/flat-out false, there’s enough notionally accurate that people have difficulty knocking it down https://t.co/0Kdi4M9dcy

— Maggie Haberman (@maggieNYT) January 3, 2018

“Notionally accurate” sounds a lot like “fake but accurate.” Do reporters covering the White House, some of whom are about to release books about the Trump presidency, believe that notional accuracy is a standard that deserves professional deference or serious attention? Haberman says Wolff got many of the basics “wrong,” which is true. But it’s not as if there are merely honest mistakes. Wolff admits upfront in the prologue that he’s throwing rumors at his readers:

Sometimes I have let the players offer their versions, in turn allowing the reader to judge them. In other instances I have, through a consistency in accounts and through sources I have come to trust, settled on a version of events I believe to be true.

This is lazy and unprofessional. Newspapers would fire reporters who engaged in this kind of shoddy reporting. The entire point of journalism is ferret out useful information, verify it, synthesize it, and give people facts and context that matters. These days, BuzzFeed might dump a discredited dossier on everyone because Trump is bad, and so let million conspiracy theories bloom, but it’s a relatively new way to do business for conventional news outlets.

Whether the president deserves tabloid treatment is not the point. There’s plenty of fodder for reporters. This is about you and malleable standards.

Wolff is a talented writer and has undeniable observational gifts; but this “too good to check” reporting is a disgrace. Most of us work hard to make sure we can verify facts before printing them. Yes we screw up sometimes but it’s devastating for us when we do. https://t.co/RfLakGDf5R

— Jonathan Swan (@jonathanvswan) January 6, 2018

It’s true that Wolff had access to the White House, and surely many of the quotes he provides are accurate. Rather than strengthen his case, this should make everyone even more skeptical of his overall account. If Trump is so bad and the administration is so incompetent and the people in it are so nefarious, there is no need to be a fabulist.

Wolff could have spent the time running down every lead and rumor he writes about. He didn’t bother, because there are few riches to be mined in meticulous, time-consuming reporting. Much of the gossip he passes along has been known to reporters, themselves eager to run with Trump-critical stories. Yet many of these stories and interactions could not be substantiated.

For all of it, Wolff is rewarded with widespread coverage. CNN media reporters will incessantly talk about the book in the guise of trying to figure out the truth — all the time pushing its contents. Chuck Todd will conduct a softball interview. Wolff will sell a bazillion copies. Other authors will have incentives to embellish their accounts of Trump. That’s because any book methodically reporting on the administration will be far less exciting to read, even if it’s far more useful.