In the wake of Roy Moore’s loss in Alabama’s special Senate election last week, together with a Republican loss in the Virginia governor’s race last month, pundits are beginning to murmur that the GOP should brace for huge losses in the 2018 midterms. Democrats, we’re told, are poised to take control of the Senate, the House of Representatives, at least five statehouses, and maybe even a half-dozen governorships. It’s going to be a blue wave. Democrats are going to capture a new American majority. Even Texas might turn blue.

This isn’t an unreasonable view to take, given Trump’s persistently dismal approval ratings and the GOP-controlled Congress’s deep unpopularity. And of course history suggests that the party of a first-term president will usually lose seats in a midterm election.

But the main problem with the blue wave theory of 2018 is that it asks too much of the Democratic Party, which is riven by as much division and confusion as the GOP is, if not more. As Ed O’Keefe and Dave Weigel reported recently in The Washington Post, Democrats “can’t agree on what the party stands for. From immigration to banking reform to taxes to sexual harassment, many in the party say it does not have a unified message to spread around the country.”

The left-wing base of the Democratic Party seems content to go out and run on a promise to impeach the president on some grounds or other, even as centrist Democratic candidates that don’t toe the Bernie Sanders-Elizabeth Warren line on everything from health care to Wall Street regulations are left to fend for themselves. What’s worse, they have no economic message. (Remember the Democrats’ “Better Deal” rollout back in July? Sort of had to do with the economy? Me neither.)

Anti-Trump Sentiment Won’t Be Enough For Democrats

Democrats might do well next year in certain swing states and districts, but they won’t sweep Republicans out of power simply by being against Trump — especially since Trump, despite his inveterate tweeting, actually has some legitimate accomplishments to point to at the end of his first year in office. If they want to win in deep-red states next year, Democrats will have to offer a positive vision for the country. There’s no sign so far they have one to offer.

Not that this is dissuading purveyors of the blue-wave narrative. A recent article in The New York Times posits that reliably GOP districts are in play as “the swelling antipathy toward Mr. Trump threatens to breach the party’s defenses and stretch the congressional battlefield beyond the dimensions Republicans and Democrats anticipated a year ago.”

Things are so bad, says the Times, even rich Republicans in Houston, Texas, might vote for Democrats! The report quotes a woman at a Democratic fundraiser in a “34-floor high-rise in the River Oaks section of Houston that was once home to Enron’s Kenneth L. Lay… and sits in the district of Representative John Culberson, a veteran Republican who may be in for the race of his life.” Culberson represents Texas’s seventh congressional district, which Hillary Clinton carried last year and has therefore drawn the attention of Democratic challengers, some of whom were outraising Culberson as of October.

But here’s what the Times piece doesn’t mention: the last Democrat to represent that district left office in 1967, when the seat went to the former chairman of the Republican Party for Harris County, one George H.W. Bush. Republicans have represented the district ever since. Culberson, who has held the seat since 2001, won reelection last year by 12 points — despite Clinton carrying the district.

Democrats Can’t Tack to the Center

All of this suggests that antipathy towards Trump might not be the silver bullet Democrats — and many Republicans, for that matter — think it’s going to be in 2018. Even in states where Democrats are relatively moderate, like Texas, their problem is akin to what ailed the moderate wing of the GOP in the 1960s and ’70s: they’re “me too” Democrats.

Texas Democrats, for example, routinely make their case along the same line Republicans do — low taxes, maintaining a business-friendly environment, keeping state government limited and unobtrusive. They just argue they’d be better at all of it. Meanwhile, the identity politics and strident culture war posture that characterizes the national party leadership simply won’t play in deep-red states, especially if Trump can, say, avoid starting a nuclear war with North Korea or presiding over a massive economic recession between now and the end of 2018.

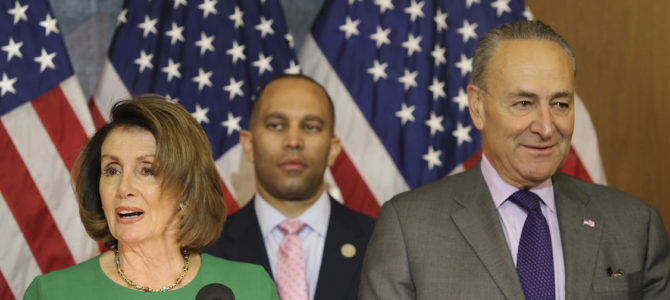

In other words, Democrats seem incapable of understanding why they won in 2006, when opposition to the Iraq War, the unpopularity of George W. Bush, and a series of high-profile Republican scandals in Congress mobilized an outraged Democratic base. In those midterms, Democrats picked up 31 seats in the House and six in the Senate, and Nancy Pelosi became the first woman to be elected speaker of the House.

But the key factor behind Democrats’ success in 2006 wasn’t a radicalized left-wing Democratic base that boosted turnout. It was because then-Rep. Rahm Emanuel helped recruit a slate of moderate, centrist candidates in swing districts that were willing to buck the party line on issues like abortion. Now the mayor of Chicago, Emanuel recently told the Times, “If you look at the patterns of where gains are being made and who is creating the foundation for those gains, it’s the same: An energized Democratic base is linking arms with disaffected suburban voters.”

The main difference between then and now, however, is that Democrats can no longer move to the center. Pelosi seems to understand that. Back in the spring, Pelosi said the Democratic Party shouldn’t demand support for abortion as a litmus test for candidates. This fall, she said the same thing about single-payer health care when she declined to endorse Sanders’ “Medicare for All” bill.

The question is: who speaks for the Democratic Party in 2018, Pelosi or Sanders? Until Democrats can answer that question, predictions of a blue wave next year are premature.