At an Indiana rally Wednesday, President Trump talked in length about congressional Republicans’ new tax plan—one that would cut both corporate and individual rates, and eliminate the “estate tax” (often referred to as the death tax), which taxes the estate of a person before it’s passed on to his or her children.

At the rally, Trump introduced Kip Tom, “a family farmer,” to his audience. Tom’s family has been farming, Trump said, for 187 years. “That could come to an end because of the death tax or the estate tax,” he said.

But as The Intercept noted in an article yesterday evening, “Tom isn’t just some small-time family farmer.” His income is well into the millions: “In addition to owning Tom Farms, he is the president of grain storage and drying firm CereServ Inc., which he reports gave him over $5 million in income during the reporting period.” What’s more, Tom Farms “is Indiana’s ninth largest recipient of farm subsidies. Between 2004 and 2014, Tom and his various companies received around $3.3 million in farm subsidies.” (You’re correct, that’s $3.3 million in taxpayer dollars.)

A farmer like Tom will still be affected by the estate tax, because he’s so rich. But it’s unlikely to be the “end” of his farm. Here’s why.

What Is the Estate Tax, Exactly?

Here’s the Internal Revenue Service’s explanation of the Estate Tax:

The Estate Tax is a tax on your right to transfer property at your death. It consists of an accounting of everything you own or have certain interests in at the date of death (Refer to Form 706 (PDF)). The fair market value of these items is used, not necessarily what you paid for them or what their values were when you acquired them. The total of all of these items is your ‘Gross Estate.’ The includible property may consist of cash and securities, real estate, insurance, trusts, annuities, business interests and other assets.

Once you have accounted for the Gross Estate, certain deductions (and in special circumstances, reductions to value) are allowed in arriving at your ‘Taxable Estate.’ These deductions may include mortgages and other debts, estate administration expenses, property that passes to surviving spouses and qualified charities. The value of some operating business interests or farms may be reduced for estates that qualify.

After the net amount is computed, the value of lifetime taxable gifts (beginning with gifts made in 1977) is added to this number and the tax is computed. The tax is then reduced by the available unified credit.

Otherwise known as the “inheritance tax” (or, among its proponents, as a “silver spoon tax”), the estate tax enables the government to get a hefty chunk of a person’s estate before it is passed on to their inheritors. This is often controversial, especially amongst Republicans, who believe the country needs to encourage family business and economic longevity.

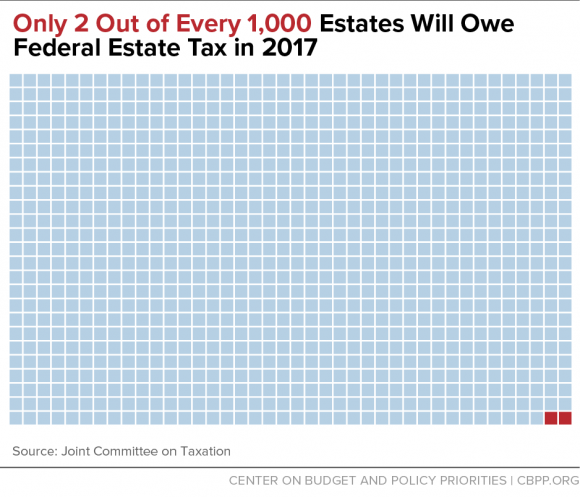

But it’s also important to note that the federal estate tax only impacts a fraction of Americans. As the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) puts it, “Only the wealthiest estates pay the tax because it is levied only on the portion of an estate’s value that exceeds a specified exemption level — $5.49 million per person (effectively $10.98 million per married couple) in 2017.” The federal estate tax thus affects about two out of every 1,000 estates (0.2 percent), according to CBPP.

But how much in taxes do these estates generally owe? According to the Tax Policy Center, while the top statutory rate is a rather staggering 40 percent, the average effective tax rate is 17 percent. The reasons for that discrepancy: “First, estate taxes are due only on the portion of an estate’s value that exceeds the exemption level; at the 2017 exemption level of $5.49 million, a $6 million estate would owe estate taxes on $510,000 at most. Second, heirs can often shield a large portion of an estate’s remaining value from taxation through generous deductions and other discounts that policymakers have enacted over time. Further, as explained below, estates use large loopholes to avoid considerable amounts of tax.”

Some of these loopholes, for agricultural producers, include a provision that “allows farm real estate to be valued at farm-use value rather than at its fair-market value, and an installment payment provision,” according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (an important rule if you farm in an area with extremely high land value, like Loudoun County, Virginia, for instance). Another provision “aimed at encouraging farmers and other landowners to donate an easement or other restriction on development has also provided additional estate tax savings.”

How the Federal Estate Tax Impacts Farmers

Does the federal estate tax affect small, family-owned farms? About 50 of them, according to the TPC. The TPC defines a small farm, in this instance, as “one with more than half its value in a farm or business and with the farm or business assets valued at less than $5 million.” This means that in order to be impacted by the federal estate tax, the farmers affected must be second-career farmers, pairing their agricultural work with some other profitable source of income (like Tom, who’s the president of CereServ Inc. in addition to being a farmer). Of these estates, the TPC estimates that they will owe on average 6 percent of their value in tax.

As to larger farms: there are more than 50,000 farms in the United States with gross sales of over a million dollars a year, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. These larger-scale farms are often commercial farms, and represent only 10 percent of the nation’s farms, but 87 percent of its food production. Many own thousands of acres and thousands of livestock animals, have contracts with large food companies like Tysons or Dole, and get a hefty amount of subsidies from the federal government (“Subsidies, which total about $14 billion a year, represent about about 5% of the gross cash income for all farms, according to USDA,” CNN Money notes).

Land isn’t the only asset that makes these estates eligible for taxation; as the USDA reports, “Farm household estates include all assets owned by the farm household—such as land, buildings, machinery, farm financial assets, pre-paid insurance, livestock, and even the value of planted crops. Farm household estates also contain nonfarm assets, such as other nonfarm business interests and assets and the farmer’s personal assets: essentially everything owned by the estate that is not related to the farm business.”

So if you own thousands of cows or a $450,000 combine, those are taxable assets—and could make up a hefty chunk of the farm’s estate: “Sixty-five percent of the value of small farm estates (farms with less than $350,000 GCFI) consists of the value of farm assets,” says the USDA, “while farm assets comprise 84 percent or more of the estates of midsize and larger farms.”

But of these larger farms, the USDA notes, only an estimated 1.7 percent of farm estates were required to file an estate tax return last year—and of those farms, only an estimated 0.42 percent owed any federal estate tax. “For the 2016 simulation, 38,328 estates were estimated to be created out of a total of 2.1 million family farms. … Farm estates estimated to owe Federal estate taxes had on average a net worth of over $11.5 million and an average tax liability ascending to $1.7 million.”

In sum, your average mom-and-pop farm in small-town Minnesota or Idaho doesn’t owe federal estate tax. Only farm estates with a substantial chunk of income and assets (being made on or off the farm) is eligible for the federal estate tax.

Some States Have Their Own Estate Tax

Some states—Washington, Oregon, Minnesota, Illinois, Maine, New York, Hawaii, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, and Washington DC—have their own estate tax, each with a much lower specified exemption level. Oregon and DC have set their level at $1 million, while New Jersey’s is only $675,000.

Meanwhile, Nebraska, Iowa, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Maryland all have an inheritance tax, with levels hovering between 0 and 18 percent. New Jersey and Maryland are the only two states that impose both an estate tax and an inheritance tax.

“The state’s economy suffers when New Jerseyans move to more tax-friendly states,” New Jersey Assemblyman Anthony M. Bucco argued in a Star-Ledger op-ed two years ago. “When they leave, their assets, business revenue, charitable contributions and employees follow. This includes small business owners as well. In a number of instances, the estate tax has prevented families from passing their longtime family farms to their children so they could carry on the family tradition.”

Washington state has established an unlimited estate tax deduction available for farmers who meet specific criteria. Minnesota has a farm deduction, which “cannot exceed $4 million.” And Oregon offers a “natural resource credit.” So many of these states are, in some way or another, trying to lessen the estate tax burden on their agricultural producers. What’s more, several states are in the process of dialing back or eliminating their estate taxes, as the Tax Foundation reports:

In 2013, Indiana sped up the repeal of its inheritance tax, retroactively to January 1, 2013. Tennessee’s estate tax will phase out fully in 2016. Maryland and New York are in the process of phasing in new, higher estate tax exemptions, eventually matching the federal exemption level ($5.9 million) by 2019. Minnesota is in the process of doubling its exemption from $1 million to $2 million over five years. The District of Columbia is slated to phase in higher exemptions to the estate tax as new revenues become available.

The Controversy of the Estate Tax

In a 2009 poll, the Tax Foundation found that Americans viewed the federal estate tax as the most “unfair” of all taxes—and 68 percent favored its outright appeal. Some of this opposition is bipartisan, as Scott Drenkard noted in a 2012 article in HuffPo: “Nobel laureate economist Joseph Stiglitz, who served as chairman on Bill Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisors, authored a paper which argued that the estate tax actually increases inequality by reducing savings and driving up returns on capital (which largely benefit wealthy holders of capital).”

He adds, “The estate tax also encourages firms to structure as corporations instead of as family businesses, because corporations do not pay estate taxes when the person at the helm changes … [t]his observation should be disconcerting to left-leaning voters, who recognize that smaller, family businesses have ties to their communities, but it should also concern right-leaning voters, who should see this as a distortion of the market process.”

While it seems the profit made from the estate tax would be hefty, a 2012 Joint Economic Committee report found that “The estate tax is the smallest source of revenue of any major tax in the United States,” according to another article by Drenkard. “In 2011, it raised roughly 0.32 percent of all federal revenue,” largely due to charitable deductions, rules, and other decisions or measures taxpayers use to avoid the estate tax. Rather amusingly, Drenkard notes, “Three studies found that the compliance costs associated with the estate planning industry exceed the revenue yield of the tax itself.”

The Estate Tax May Hurt More Than It Helps

Throughout the last four years I’ve spent researching family farming, few people have brought up the death tax as a serious problem. Of those, a few were farmers living in states like Oregon, which are subject to lower levels of elibigility. Others were wealthy business owners who are themselves eligible for the federal estate tax, and likely assume a large portion family farmers share the same burden.

There’s a strong free-market, pro-family business argument for abolishing the federal estate tax. As states across the United States work to either abolish their taxes or raise applicable levels, it’s more than likely that on-the-ground experience is reinforcing the supposition that this tax causes more headaches and economic difficulty than it does political or financial advantages.

If the government really wants to take money away from the country’s biggest industrial ag producers and make things “fairer” for smaller farmers and business owners, it should probably look to reforming the Farm Bill’s crony subsidies and crop insurance, which hugely benefit the nation’s largest ag producers—not hold on to the federal estate tax.